Salt and Society

Google ‘Titus Salt’ (1803 - 1876) and you will come up with a range of key words and topics which may well chime with our conception of who Sir Titus was and what he sought to achieve.

‘Manufacturer, politician and philanthropist’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Titus_Salt)

‘Largest employer in Bradford’ but ‘Bradford gained the reputation of being the most polluted town in England’ (https://spartacus-educational.com/IRsalt.htm)

‘alpaca hair’, ‘produced a new class of goods’ and ‘Saltaire [became] … the most complete model manufacturing town in the world’ (https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1900/Salt,_Titus)

But read the histories more carefully and you will find that the story was, inevitably, far more complex than many of us might perceive. Did Salt make a lasting difference? Was he interested in philanthropy or was it a form of social engineering? And what is his legacy?

Most commentators appear to agree that Titus Salt, a man of relatively humble origins, was truly appalled by the conditions prevailing in Bradford in the first half of the 19th century.

After two years as a wool-stapler or wool trader in Wakefield, Salt moved, in 1822, to Bradford and eventually joined his father who had also set up as a wool-stapler. Salt junior seems to have introduced a Russian Donskoi wool, but found that the Bradford wool mills refused to handle this rough product, so he worked on creating specialist machinery which could handle the wool and set up a mill of his own.

By 1836 he had four mills and, after the purchase of a large supply of alpaca hair, no doubt going at a knock down price for the same reason as the tangled Donskoi wool, he introduced a new alpaca textile and became a very wealthy man.

Meanwhile the population of Bradford had expanded hugely (an eightfold increase over the first five decades of the century) and conditions for the mill workers are reported to have been dire. Over 200 factory chimneys belching smoke, sewage polluting drinking water, outbreaks of cholera and typhoid and appalling levels of infant mortality (see https://spartacus-educational.com/IRsalt.htm for a graphic account of the conditions). Salt discovered that the Rodda Smoke Burner significantly reduced stack emissions but failed to persuade fellow mill owners to install it as he had done in his own mills.

Construction of Salt’s new model factory commenced in 1851 and took two years to build. The site was three miles outside Bradford’s polluted city centre on the banks of the river Aire, the Leeds and Liverpool Canal and the Midland Railway. A very rural and yet very connected site.

Map image reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

The whole site was listed as UNESCO world heritage in 2021 (https://saltairevillage.info/). Salt’s Mill, as the Italianate mill building is now called (listed Grade II*) (above), was designed by Lockwood and Mawson as a ‘Palace of Industry’. It faced the railway and ‘was to be, externally, a symmetrical building, beautiful to look at, and, internally, complete with all the appliances that science and wealth could command’. Money was no object and indeed, it is reported that ‘Lockwood and Mawson’s first design for the mill, costed at £100,000, was rejected by Salt as being ‘not half large enough’.’ (https://saltairevillage.info/Saltaire_WHS_Salts_Mill.html).

Today it functions as a Hockney gallery and retail space. When Terroir visited, the ground floor was full of colour, vibrancy, excitement - and lots of upmarket retail opportunities. Upstairs, the queue for the ‘Diner’ was far from exciting, so we went elsewhere.

Once the mill was up and running, a dining room was constructed and then 850 houses - hammer dressed stone with Welsh slate roofs - so that Salt’s 3,500 workers no longer had to commute by special train from Bradford. Each house had its own outside toilet, gas for lighting and heating, and a water supply.

Evidence of the outside toilets is now hard to find, although perhaps the structure with black door, image left, just might have been one?

The tight street grid (below left) of ‘through terraces’ are topped and tailed by larger dwellings (below right), like mini castles protecting their two-up two-down terrraces (below centre) from some unknown threat.

The tiny front gardens are as varied as anything can be in an area of blanket listed buildings (grade II*), located in a Conservation Area, located in a World Heritage Site. Even these designations are not proof, however, against the modern townscape horrors of parked cars and wheelie bins.

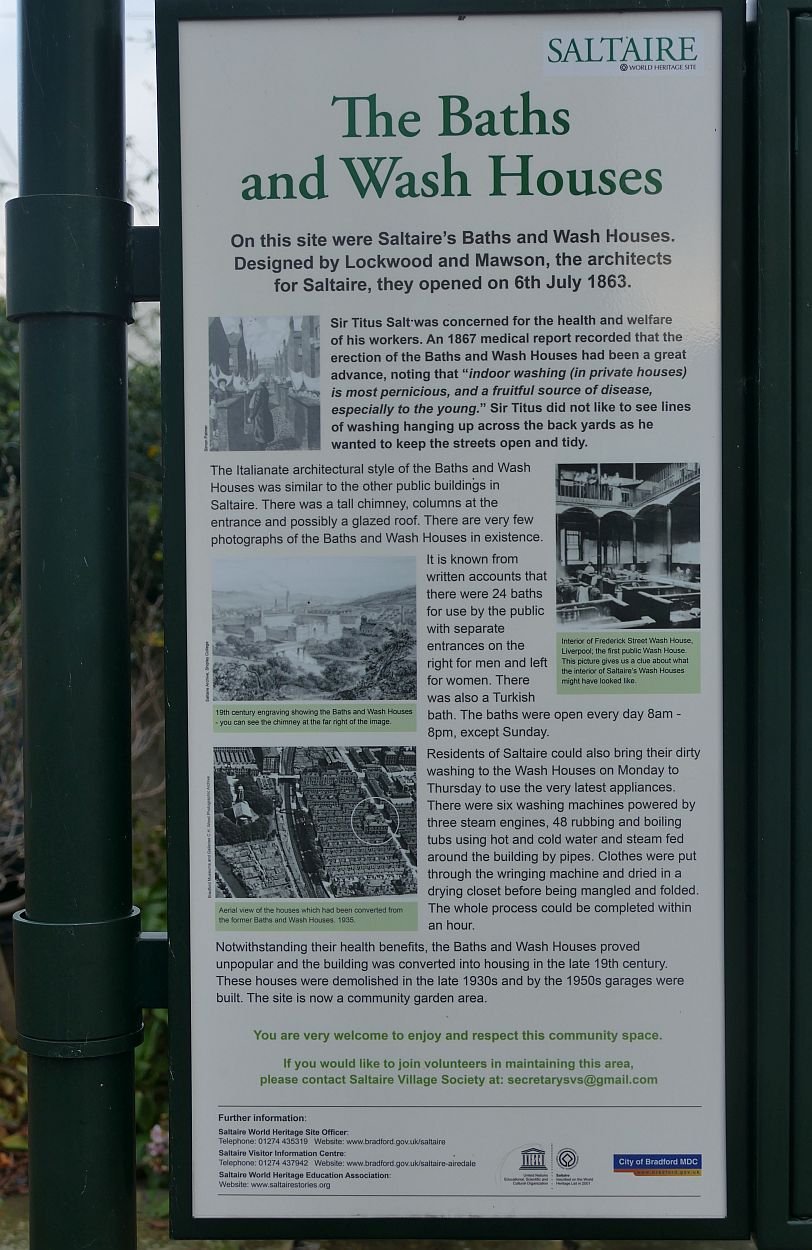

The housing areas were supplied with substantial bath and wash houses, but these were not popular. One suspects that the novelty of running water and gas heating in the comfort of one’s own home made lugging the washing down the street on a wet Yorkshire morning an unattractive prospect. The site of one such Bath and Wash House is marked with a well illustrated information board (below left) and the space is now planted up as a pleasant pocket park (below right).

There followed the addition of other amenities: the Congregational Church (now a United Reformed) (below left) and the Saltaire Institute (now Victoria Hall) (below centre and right).

There were also a school, a hospital (below left and centre) and alms houses (below right).

Were Salt’s motives purely philanthropic? Would his time, energy and money have been better sent improving working conditions for all, for instance through campaigning and legislation? Or did his model town show to best advantage what could be achieved, either voluntarily or by statute? We will return to this aspect later. What happened, one wonders, to employees who could no longer work in the factory through ill health or infirmity? The Alms houses are reported to have offered rent and tax free accommodation, plus a weekly stipend, but only for a maximum of 60 people. Was this sufficient? Were families thrown on the streets if the main bread winner died ‘in service’?

Other model villages have been accused of paternalism and even social engineering. (For instance, Helen Chance, ‘Chocolate Heaven to Tech Nirvana’, https://www.folar.uk/folar-talks). Chance and Terroir are not the only cynics. Wikipedia quotes David James (Oxford Dictionary of Biography)

‘Salt's motives in building Saltaire remain obscure. They seem to have been a mixture of sound economics, Christian duty, and a desire to have effective control over his workforce.’ James continues: ‘the village may have been a way of demonstrating the extent of his wealth and power. Lastly, he may also have seen it as a means of establishing an industrial dynasty to match the landed estates of his Bradford contemporaries.’

Does this matter, if 3,500 people had decent living conditions?

Today, after major regeneration in the 1980s, Salt’s building project has created a new town of World Heritage Standard, much of which consists of very desirable private residences. Property prices are low in Bradford, but Salt’s cottages sell for about double the price of similar sized property elsewhere in the City. Obviously location and architecture count for a lot, although this may be tempered by difficult parking and, as noted above, a heavily regulated environment.

But Salt left one legacy which still offers as much today - in terms of accessibility, health, social and environmental benefits - as it did in the mid 19th century. This legacy is Saltaire Park, now known as Roberts Park.

Opened in 1871, the 6 ha park was designed by William Gay. Gay was probably better known for his cemeteries but his parks, included Horton Park in Bradford (registered Grade II) as well as the Grade II Saltaire Park (https://www.parksandgardens.org/places/roberts-park-baildon).

Bordering the north side of the River Aire, Gay laid out the river side meadow as a generous, grassy space for cricket and croquet, bathing and boating and informal recreation generally. Making use of a slight slope behind, he created a promenade with bandstand overlooking the cricket ground, and serpentine paths winding through ornamental planting. Refreshment rooms were built into the bank below the promenade. A bronze statue of Titus Salt was added in 1903.

By the beginning of the 21st century, the Park was in need of some attention and a successful Heritage/Big Lottery Fund grant enabled a £1.3 million restoration project which was completed in 2010. Gay’s layout has been retained but the park now benefits from a new playground, rehabilitated Park shelters and lodge, as well as Gay’s - now mature - trees towering over rejuvenated planting and paths .

Cricket is still played, observed by Sir Titus himself and two of his alpacas, who appear to be checking the boundary to confirm four runs.

The project also included a replacement bandstand, as the original had been removed some time previously and its companion canons, one of which is reputed to have been fired at the Battle of Trafalgar, had been melted down as part of the war effort in World War II. The replacement artillery (below left) consists of two 19th century canons, produced in a Bradford Ironworks, although never used in anger. The bandstand is not only decorative, but multifunctional (below right)

Other significant restored features are the three, very decorative, park shelters (two examples below left and right) and the park lodge, rescued from dereliction and put to community use.

Gay’s now massive Corsican pines add grandeur and height to a site which lacks somewhat in level changes. Gay underplanted with hollies and one suspects that these have been massively reduced, controlled and managed to ensure tempting vistas within the park and views to and from the shelters (very welcome on a dreary December Sunday). Roses and magnolias must be a feature in spring and summer and the all-year-round mixed planting beds contributed to a very satisfactory winter walk. The restored promenade and serpentine paths make ‘access-for-all’ not just possible, but a real pleasure.

So why did Saltaire Park become Roberts Park? Many sources applaud Salt’s philanthropy, note that he was amongst the wealthiest of the Bradford textile ‘barons’, that he gave away perhaps half a million pounds to good causes during his lifetime, and that, although he did not invest in a landed estate as many others had done, he did provide his family with a comfortable family home (Crow Nest). At his death in 1876, his legacy was Saltaire model town, already famous for its humanitarian principles. But that was it; he did not leave his family any money. The estate went into administration in 1892 and was bought by a consortium of four business men, one of whom was Sir James Roberts. The mill and town retained Salts name but the Park did not.

Where did Salt’s fortune go? Textile prices were falling towards the end of 19th century, yet other mill owners survived. Was Salt a poor manager, incapable of technological change, or financial wizardry? Or did he put philanthropy (or his ego) before profit? I don’t know. Neither can Terroir comment on whether Saltaire had any long term impact on reform of working conditions or social security.

What Salt did leave, however, is Saltaire Park. Here is a legacy which keeps on giving, keeps on improving people’s lives and, thanks to enlightened management and the Lottery grant, probably benefits more people now than it has ever done before. Ironic about the name.