A good grouse?

Are we too grumpy? Maybe we all need to get out more.

Last summer, when we could (get out more), we spent some time walking in the Derbyshire side of the Peak District. I hasten to add that these were legitimate walks, although we did keep a sharp lookout for the Derbyshire Constabulary and for lagoons which had turned a suspicious shade of black. Little did we know that carrying a takeaway coffee would later become an icon of Derbyshire lockdown bad temper and an extreme interpretation of recreational rules.

What is it about Derbyshire which puts people out of sorts? We are certain that the Derbyshire community, as a whole, is not to blame. We know for sure, however, that areas of beautiful, dramatic and inspiring landscape such as the Peak District or the Lake District create intense human passions – often about protection, conservation, access, management and policing - which may polarise views and create adversarial situations.

The 1932 mass trespass on Kinder Scout, which drew support from both sides of the Pennines, is a classic case in point. The fact that it took a further 80 years to pass legislation which allowed any form of open access to landscapes such as these, is enough to make anybody irritable. We refer, of course to the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 (the CROW Act). Even the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949, which recognised the significance of these landscapes, if not of universal access, had to wait 17 years to reach the statute book, after a gestation period which included WWII. The Peak District was the first National Park to be designated, and this year sees its 70th birthday. But not even this anniversary seems sufficient to create universal joy and good will to all.

As an example of some of the issues which make landscape management so ‘interesting’, and defusing conflict so important, we will take a look at some of the walks which we enjoyed so much last summer. There was considerable debate between the three of us who took part but not, I am pleased to report, a single cross word. Do I hear laughter in the background?

Ladybower Reservoir and Win Hill

Let’s start off by being petty: nice bit of traditional waymarking but the plethora of roundels makes a bit of a nonsense of the ‘Public Footpath’ message!

More seriously, did they really need to mow the down stream slope of the reservoir dam in the monocultural, English garden style? It seems possible to accept a more diverse and sustainable ground flora beneath the scrub and bushes on the left of the photo, and around the photographer’s feet.

We’ll pick up the non native coniferous planting later.

Ladybower Reservoir was constructed between 1935 and 1943 to quench the thirst of the expanding industrial towns surrounding the Peak District. The long, deep valleys of the rivers Ashop and Derwent, the high rainfall and low popuation, made the area seem ideal for water storage. The population was not non-existant, however, and two villages, Ashopton and Derwent, were flooded and their population moved to an estate downstream of the dam. They must have found it galling to discover that ‘Derwent's packhorse bridge, spanning the River Derwent … was removed stone by stone to be rebuilt elsewhere as it was designated a monument of national importance’. And that, ‘The church spir' was left intact to form a memorial to Derwent. However, it was dynamited on 15 December 1947, on the rationale of safety concern’. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ladybower_Reservoir

Of course, after WWII, the attitude to planning and infrastructure changed significantly. In the 1950s and 60s, the plans for the Llyn Celyn reservoir in Gwynedd caused deep controversy. Despite the degree of protest, the village of Capel Celyn and its valley, located in a stronghold area of Welsh culture and language, was flooded to provide water for the - English - city of Liverpool.

Do people grouse about Ladybower today? It is a large of expanse of open water, beloved by thousands of tourists. But - parking and traffic creates a management nightmare. It provides drinking water, but access to the reservoir is controlled with limited recreational uses including no swimming (potentially hazardous). Architecturally, it is imposing and technologically, interesting. It looks wonderful when full of water, much less so in a drought, and probably a potential nightmare to manage access when the water level is so low that you see the remnant village.

Let’s move on to the top of Win Hill and look at the view.

Oh look - lots of issues here! On the plus side, there is no one else around, so those of us who love getting away from it all are very happy. But we did get up early to achieve this. We don’t see this as a problem, however. Self-managing the timing of our access to potentially busy areas is part of the challenge.

But obviously, lots of other people have been here and the photo hints at the erosion that all those walkers have caused. In the early days of the Pennine Way this was a serious problem, and much of the route has been paved to overcome the ‘sea of mud’ crisis. This is a sensible solution, which increases access but does diminish the wilderness feel. I was worried during our recent wet winter that the ‘sea of mud’ look created by a lockdown population desperate to get out and keep sane, would bring out the worst in our open space managers. What a swell of pride when the response was basically, ‘don’t worry, keep coming, we’ll sort it out later’.

And the view? What’s that lurking in the distance, sporting a high chimney and a massive quarry? It’s the Bredon Hope Cement Works, with the village of Hope nestling in the Valley below. The up side? It all started in the late 1920s, long before planning legislation and the designation of the National Park, but environmental control is much stricter now.

Lots of the finished product goes out by rail (left), so minimal impact on road transport.

Provision of local employment - Bredon says the company is ‘the area’s largest employers with the majority of the 200-strong workforce at Hope living in the Peak District’ and that they employ a ‘diverse range of people’. https://www.hopecementworks.co.uk/about/

Down side? Big energy user and lots of CO2 goes up the chimney. Damage to visual amenity? You decide. At this distance, we thought it rather interesting and a demonstration of geography in the raw (the plant is here because the required limestone is here). Living next to it, may produce a different answer, however.

Don’t like it? One of the great 21st century challenges is finding alternatives to, in this case, building materials, to reduce negative impacts. On delving deeper, alternatives can often be worse than the existing situation. Ingenuity essential.

Thanks to Wikipedia for some help with the above. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hope_Cement_Works

Strines Moor and the real grouse.

Grouse moors: where to start. So many issues, so many points of view.

Shooting and grouse moors were a big part of the original Right to Roam debate. The few owned vast acreages of moorland and denied access to the many. It was still an issue in the CROW Act which does allow for short term closures of open access land to allow for shooting.

You could devote a whole blog to intensive grouse shooting and grouse moor management and indeed Terroir was planning to do this until we came across Guy Shrubsole’s blog post on ‘Who Owns England?’ https://whoownsengland.org/ Do read his January post, entitled ‘The Climate Sceptics Grouse Moor’ which, although a diatribe against one particular moorland owner, gives an overview of some of the issues. Read all his links too, to get a view of both sides of the argument. Both the hunting and shooting orgnisations and the environmental press argue lucidly for and against intensive grouse shooting.

Here is a quick round up of the main issues. We have already mentioned access, so we will move onto the management debate. Rotational cutting, burning and draining of grouse moors is standard practice. If cut back, heather re-grows until it becomes ‘over mature’ - tall and leggy - when, if cut back again, it will restart the growth cycle. Each part of the cycle has its ecological advantages and so it is not uncommon, on any form of heathland, to cut areas on a rotational basis and try to mimic former and traditional management via grazing and burning.

Above - classic pictures of rotational cutting of upland moorland for grouse shooting. The patterns are wonderful and I would happily upholster my sofa in something based on this, but the ecological implications are less appealing.

Grazing and burning of lowland heaths, often in urban areas, is not really attempted any more for reasons of livestock welfare and control and, for burning, for reasons of pollution, and burn control, particularly in areas heavily used for recreation. On upland moorland, the substrate is often peat, which puts a whole different perspective on the matter. Peat is regarded as an excellent carbon store and burning and drainage is seriously damaging to peat. Strines Moor is classified as Upland Heath (https://magic.defra.gov.uk/MagicMap.aspx) which means peat depth may be limited to ‘only’ 50 cms deep, but there is plenty of blanket bog in the area, and the name is an excellent description.

Of course, species conservation and biodiversity is also part of the debate with game keeper and ecologist fighting it out on who can best conserve and manage heath and bog vegetation, ground nesting birds, raptors, butterflies and … . You get the picture.

Tree planting is the other ‘Big One’, which must be discussed.

Deciduous woodland beside Ladybower Reservoir

One of the big upland debates centres on trees. Visitors love the windswept uplands, with their stunning views, ‘wilderness’ experiences and complete contrast to an urban and often industrial home environment. The Forestry Commission loved the open uplands for their unobstructed tree planting options. Don’t forget that the Commission was set up in 1919 after the terrible experiences of WWI, to provide a strategic resource of timber, should such a conflict ever re-occur. Of course, it did re-occur but by 1939 the new plantations were at best only twenty years old and even the fast growing, non native conifers were not of a size or condition to deliver.

Post war, support for planting non-native and non-local timber conifers continued with a mix of enticing tax breaks for those owning large estates, and a range of grant funding. In my view the economics never stacked up, but the promise of jam today more than compensated for the lack of jam/income at maturity and felling. Criticism of the visual impact of the sitka spruce farms and of damage to biodiversity and native habitat became increasingly vocal. To encapsulate over half a century of grumpiness into one sentence, changes were made in planting design, management and species choice, and the governmental approach shifted to include access and nature conservation as prime objectives along with timber production. The grant forms became harder and harder to understand/complete, so just about everyone had something to moan about.

With increased understanding and awareness of climate change, the whole tree planting thing shifted gear once again. Here is a flavour of some of the issues (it’s extraordinarily complex, so please don’t expect a comprehensive run down, details, or academic verification). Trees absorb carbon as they grow, but they grow very slowly. Alternative carbon sinks are available. Managing woodland to create a continuous supply of fuel might be close to carbon neutral, but wood smoke contributes to air pollution and we are already banned from burning ‘wet wood’ (more than 20% moisture content), please note if you own a wood burning stove. Mass tree planting can do more harm than good and this is a serious issue. We were incandescent over an episode of BBC’s Countryfile, which appeared to be supporting mass planting of a single non-native conifer, in Northumberland. I thought we got over that approach last century.

Tree planting will be and should be one of the pieces in the carbon control jigsaw but, as with peat, it’s not as easy as it looks. Tree planting must use appropriate, preferably native - and locally native - species and mixes, or our wildlife and ecology will be sunk. It must also take into account other landuses and habitats, which may actually be more valuable than new tree planting - yes, really - otherwise our ability to sustain, diversify and also feed ourselves will be significantly damaged. It must be in an appropriate place in the landscape, taking into account our love of the hills, views, access, and the needs of human beings, or our history and society will go down too.

To do all of this, we must have appropriate leadership, support and guidance from our government and its advisers. We must learn lessons from the Corona epidemic. And we must do it on a global scale.

End of rant, but it is rather important.

Pond Life

If last week’s blog discussed the environment of Thornton Heath’s present day fishy experiences, then this week’s sequel will focus on a historically watery habitat. We are going from Thornton Heath’s fish shops to Thornton Heath Pond. We will return, via a new open space opposite the station, to complete our circuit.

The maps included in last week’s post clearly show that, in the 19th century, the heart of Thornton Heath lurched eastwards, from the original hamlet around the Pond to the station, and then beyond again to the newly-created, semi-circular High Street. The pulling power of the Victorian railway system was, in all senses of the word, vastly superior to the speed, comfort and carrying capacity of the Victorian road system. Today, of course, road transport is favoured, but it also delivers a significant, negative environmental impact. Thornton Heath High Street, originally a product of train travel, appears to have responded well to regeneration works but what has happened to the road transport dominated ‘Pond’?

It is a good mile from the High Street to the Pond so, after our exploration of Thornton east, we save our legs and take a bus to go west to the Pond. To be honest we got the wrong bus so come upon Thornton Heath Pond from the south rather than from the east.

Approaching Thornton Heath Pond along the old London to Brighton Road you cannot but believe that this vast gyratory will be a polluted, noisy, dusty, litter-strewn, cracked paving, broken tarmac-ed, and unpleasant experience.

© Google Maps 2021

To reach the centre you have, by necessity, to cross busy roads. Threading your way over a traffic ‘skerry’ (island is too comforting and romantic a word) with an untidy growth of poles supporting traffic lights, signposts and cameras, it is at best uninspiring and at worst confusing and downright depressing. The only nod to local identity – a kind of low, urban, metal hurdle adorned with golden baubles and announcing ‘ornton Heath Pond’ - has already been adapted to carry the modern equivalent of fly posting.

Emerging on the other side, there is another scatter of vertical elements and lumpy skerries but the impact is both surprising and altogether more pleasing. Dimensions, materials, spacing and sight lines have created a sense of arrival and of calm. Who would have thought that the centre of a roundabout could become a destination, a place to sit in the sun, a place to watch the shadows etching patterns on the ground, a place to admire the daffodils, tulips, new leaves and blossom. One of the boulders even turns out to be a Croydon Stone.

The remnant of the pond lies at the other end of this almost-bean-shaped traffic island. A path, delineated by low brick walls, offers a pleasant promenade down into the grassy bottom, which is itself edged by further walls or vegetated banks. It doesn’t take much to imagine it full of water. Considerable efforts have been made to decorate the walls, and the perimeter trees on the ‘banks’ provide structure, shade, interest and significantly dilute the impact of the circling traffic (although I might not be saying that during a wet and non-Covid rush hour).

Some would say that the perimeter banks, the planting areas and even the grassed area within the ‘pond’ itself are neglected and weedy, but in spring time we find them totally inoffensive, indeed a real bonus for a heavily urbanised area of south London located in the centre of a roundabout. The impact of a wide selection of native wild flowers, all blooming, all self-generating in their rough grassy matrix, gave enormous pleasure. We logged red dead nettle (Lamium purpureum), groundsel (Senecio vulgaris), dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), shepherds purse (Capsella bursa-pastores) chickweed (Stellaria media), daisy (Bellis perennis), forget-me-knot (Myosotis arvensis or similar garden escape!), yarrow (Achillea millefolium), buttercup (Ranunculus acris) and an umbel which the photographer slipped in without identifying…).

We will revisit later in the year to see how this landscape copes with other seasons.

Also on the plus side, I did find subtle evidence of maintenance. The path edges had been cleared, trees maintained, and there was precious little litter. An extraordinary range of people were either walking though or sitting and enjoying the sunshine and the delights of such an unusual open space. Even the noisy bunch of young men who turned up to sit on the walls were soon relaxing, quietening down and generally merging into the magic of the environment.

Perhaps the lonely, off-centre, tree-less, commemorative planter fails to make the grade. Perhaps the place is a nightmare in the dark, perhaps …. But on that day, in that weather, at that time of year it was an extraordinary, surprising and pleasant experience.

But there is another open space we need to visit before we take the train home.

Walking up Brigstock Road from Pond to Station we pass more street murals which do exactly what they are meant to do and reinforce our upbeat mood.

Opposite the station, we come to Ambassador House. We will let the Thornton Heath Chronicle (online edition, 28/10/18) make the introductions:

‘The iconic Thornton Heath eyesore Ambassador House is being squatted by a collective of artists, The Chronicle can exclusively reveal.

The group of five have taken over the vacant building which has been empty since it was bought at auction in October 2012 by Red Wing Property Holdings Ltd … .

The group wants to open up the redundant office space to the community and has begun putting in place precautions to meet health and safety requirements as well as setting up an account to pay for the utilities.

Ambassador House was was[sic] once a busy hub, with offices used by CALAT, the Met Police, and Croydon council.’

How interesting. But back to the Thornton Heath Chronicle online (6/12/19):

‘Last year the council launched a competition to transform the Ambassador House forecourt.

A year later this is the result – a mural and and an unfinished garden. …

Following the announcement of the winners, a collective of architects, public consultations were held resulting in a grand design. A mural was painted and then months spent creating a garden by the bus stop which is full of weeds …

Then out of no where the forecourt was back in the spotlight. The council had done a deal with Timberland as part of its Nature Needs Heroes campaign with Croydon rapper Loyle Carner declaring plans to green up the area. The forecourt was cordoned off and transformed in to a trendy venue with marquee and a concert stage and the public hurriedly invited on a week day to look at the plans, though to the untrained eye looked much the same plans. …

The latest date to install and launch the square is April 2020. Watch this space!’

So we did watch this space and this is what we found.

It’s bright, it’s fun, it’s brash and in your face. It’s so much better than a weedy bus stop. It’s also lunchtime. Where are the people? It’s pretty much empty. It’s long and thin, and feels tight, small. To us, back from the sunshine over Thornton Heath Pond, it feels drafty, lacking focus and depth. We are probably being very unfair; It’s probably heaving in the sunshine, on a weekday, when there is an event on, when the shops are open. But today? It lacks the spontaneity, the people, the nooks and crannies of the Pond. It feels more like a thoroughfare than a place to linger. The Pond was obviously used as an access - it’s in the middle of four major roads for goodness sake, and walking through is a far pleasanter experience than walking around - but it also felt like a place where you could ‘dwell’ for a moment or for a while.

So, sorry Ambassador House. We want to pick up a wrap or a samosa from one of those exciting shops in the High Street but its too far in the wrong direction, so we’ll find something in equally multi-cultural Broad Green on our way to East Croydon Station. This space is too well-tailored, too sterile for our current needs. Espeially when the station building, wrapped in scaffolding, can’t contribute anything to the street scene either!

So we will bid you farewll with a taste of some of Thornton Heath’s best banners.

An uproar of amazingness

Fish for supper? Fancy a surprising south London suburban stroll? Welcome to Thornton Heath.

The reason we went to Thornton Heath was to look at some art work at the station, of which more later, but having arrived by train it seemed churlish, and unlike Terroir, to go home after just viewing that mosaic on platform 1. So we climbed up to the High Street and spent a few hours exploring the wider suburban landscape. It’s quite an eyeful.

St Alban the Martyr’s Church

Building started in 1889 but contined in stages until 1939. It is listed grade II

Architects: William Bucknall & Sir Ninian Comper

But let’s start by going back a bit. In case you don’t know, and that may be quite a lot of you, Thornton Heath is in south London, just to the north of Croydon. One of the better known local landmarks is Thornton Heath Pond, not because you can picnic or feed the ducks there (you can’t) but because of the adjacent bus depot and the number of red London buses which carry ‘Thornton Heath Pond’ as their final destination. But it does sound delightfully rural, atmospheric and a worthy - if somewhat mythic - destination, just like the Purley Fountain, to the south of Croydon. And, just like the Purley Fountain, Thornton Heath Pond, is now the centre of a very busy roundabout.

In August 2018, the Croydon Advertiser asked the inevitable question, ‘Why is there no water at Thornton Heath Pond?’ (https://www.croydonadvertiser.co.uk/news/croydon-news/no-water-thornton-heath-pond-1939675). Part of the answer went as follows:

‘Centuries ago, before the busy roads were built, Thornton Heath actually was a heath. Acres of common land stretched across the area, and the ancient grazing land was used by Medieval farmers to feed their animals.

Their livestock could also take a drink at the watering-hole at the heart of the heath which would later become the eponymous Pond.

The area – now part of London's most populous borough – was once a rural and isolated spot.’

The London to Sussex Road (now the A23 London to Brighton road) also passed by the pond and is probably the reason the area became famous for highwaymen. An interesting Wikipedia article (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Thornton_Heath) suggests that Dick Turpin was associated with the area (via a local aunt - families, eh?) and that a ‘plot of land at the Pond became known as Hangman's Acre. Immense gallows loomed on John Ogilby's Britannia maps of 1675, and were still present in a later edition in 1731.’ The account goes on to suggest that in the 17th and 18th centuries Thornton Heath was ‘a desolate valley with lonely farmsteads sheltering desperate outlaws, with the hangman's noose the only recognised authority.’

The other local activity of note is commemorated by Colliers Water Lane, a local street name which still exists, and whose origins were linked to the romantic sounding Great North Wood. Remember, however, that this area is culturally both the south of England and ‘south-of-the-river’, so that the Great North Wood didn’t even get to Watford, but stopped abruptly on the south bank of the River Thames. The Colliers were charcoal burners who, according to the Wikipedia article, burnt timber from the Norwood Hills, using cooling water from the adjacent Norbury Brook. The concept of ‘north’ must have had a deep psychological impact on Croydon and the south. Wikipedia continues, ‘Smoke and high prices made the Thornton Heath colliers unpopular. With their dark [presumably in the sense of grimy?] complexions, they were often portrayed in the popular imagination as the devil incarnate.’

Back to the Croydon Advertiser: ‘In the early 19 century the well-to-do started to build their grand houses along the London Road [or, as William Cobbett described them less politely, ‘stock-jobbers’ houses’] , and the village surrounding the pond began to attract tradesmen.

New tastes and wealthier citizens led to the one-time watering-hole being given an upgrade – formal railings were installed to circle the water-feature, which became the decorative heart of the area.’

What the Croydon Advertiser forgot to mention is that, prior to the 19th century ribbon development, the land surrounding Thornton Heath had been enclosed (in the 1790s), and had become a landscape of small fields, farms, woodlands and the occasional orchard; no doubt very bucolic but enclosure meant that the control of the land would now have been in the hands of a very small number of people.

With the development of the Surrey Iron Railway (Croydon to Wandsworth section) in 1803, and the Croydon Canal (Croydon to New Cross via Forest Hill), in 1809, both passing close to the south of Thornton Heath Pond, plus the existing importance of the London to Sussex road, probably made investment in the Thornton Heath Pond settlement an attractive proposition. Instead of agricultural improvements to his newly enclosed fields, a beneficiary of the enclosures, one Thomas Farley, ‘converted allotments of land and sold them as freehold property. As a result, by 1818, the hamlet around the Pond had become a considerable village containing 68 houses’ (Wikipedia). One suspects that it was not quite the windswept heath which the newspaper report implied.

The sign of the Thomas Farley Public House, High Street, Thornton Heath

The pub has closed but, perhaps appropriately, has been converted into residential accommodation.

But it was the Victorian railway boom which initiated the major conversion of Thornton Heath from urban fringe to full on south London suburbia. Where railway lines had not been routed through existing settlements, stations such as Thornton Heath (constructed in 1862) were built in the middle of farmland. Again, those who had done so well out of the enclosures, recognised that they were sitting on prime real estate and, within ten years, the area of housing around the station was larger and more significant than the road hub, almost a mile away, around the Pond.

The maps below tell their own story, with the railway stimulating residential development far more rapidly around the station than around the pond/village/highway combination.

Ordnance Survey 1894/95 Revision, showing both pond and railway station

Pond - blue circle Station - red circle

All map images 'Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland' https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

21st century Thornton Heath has a far more diverse demographic than the community which formed around the station in the late 18th century. But times are tough and, in 2010, most of the area between and around the station and the pond was recorded as lying in the more deprived end of the multiple deprivation spectrum. By 2015, the situation worsened but some improvement is shown in the 2019 statistics. Indeed Croydon Council has been working on the regeneration and improvement of the Thornton Heath environment since 2016 and around £3 million pounds has been invested, on shop and building front improvements, on artworks and on open space. The methodology behind this work deserves a blog in its own right but, for now, Terroir will take you on a tour of the delights of Thornton Heath and try to demonstrate why we so enjoyed our morning of sight seeing.

If you arrive by train, look out for two things.

The first, left, delivers a bit of a mixed message.

We are happy to be welcomed to Thornton Heath, but are wary of the anti-climbing device on the top of the wall!

This, right, is what we have actually come to see.

It is one of 14 such roundels currently adorning 11 stations around London.

The roundels are the work of Artyface, founded by Maud Milton in 1999, ‘to provide high quality, legacy public art’ with community involvement at its core. Her website is a delight (https://artyface.co.uk/wp/) and if you ever need cheering up, just take a browse.

The Station roundels project was developed out of a partnership with Arriva. Maud and team worked with 3,000 members of the relevant local communities to create the designs for the first 13 roundels which are all noth-of-the-river, mainly on the London Overground.

The most recent roundel has been devloped for Govia Trains and the Thornton Heath community. The detail is phenomonal and tells its own story.

Leaving the station for our ‘well we might as well take a look while we’re here’ expedition, we turn to the left to head east - away from the Pond. Turning around to take a photograph of the 1860s station building, we are gutted to find that it is encased in the warm embrace of extensive scaffolding. A bad start for the photographer.

Our next discovery was the clock tower and the Croydon stones. The clock tower, which also seems to feature as an iconic bus stop, in a similar manner to the Pond, was erected in 1900 to celebrate the new century. According to the Thornton Heath Chronicle, it suffered a minor arson attack last year but appeared, to Terroir, to be in good condition last Saturday. Neither were there any signs of the ‘street drinkers’ who the Chronical reported to have been plaguing the area.

Left: the Thorton Heath Clock Tower

Below: one of the Croydon Stones

After this sedate history lesson, things really began to hot up as we rounded the corner and moved onto the High Street. It was a blast - first the murals, then the building facades, and then the shops themsleves.

We turned off up a side road, to see what went on behind the behind the High Street and were taken aback - again - by the extraordinary contrast offered by the suburban streets. How could anywhere so close to that vibrant, brightly coloured and noisy high street be so quiet and so calm. We could hear the birds singing and we couldn’t hear the traffic. How is it done?

We walked up hill, discussing how we would like to live here, as long as there was a park or open space nearby. As if by magic, we came across the entrance to Grangewood Park. As we entered, the magic did rub off a little, however, as the steep gradient put paid to our day-dreams of spending our twilight years here. If any octogenarians were to make it their daily walk, they would certainly be very fit. Grangewood Park is a relic of a much older estate which was originally part of, guess what? the Great North Wood (https://www.thorntonheathchronicle.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Grangewood-Booklet-v6.pdf). Today the southern lodge is boarded up, the scattered trees look tired (and what is that tent doing in the second picture from the left?), the ground flora is trampled down and the soil looks heavily compacted. Spring seems a little far away, although a Monkey Puzzle tree and some sparkling new gym equipment do lift the spirits.

We zig-zagged back through more amazingly peaceful - and clean - streets, spotting our favourite bits of suburban architecture.

Back on the High Street, we had to face up to the big question. Why were there so many fish shops? We don’t mean fish and chip shops or fish restaurants, we mean wet fish shops, fishmongers, shops that sell fresh fish. Some just sold fish, some sold fish and a variety of groceries or vegetables. We wouldn’t have been surprised if the newsagents had had a fish counter. Why is Thornton Heath fish heaven? If you know please put a comment at the bottom of this blog.

Talking of which, we will postpone the rest of our voyage through Thornton Heath until next week, as there are one or two suprises still to come. But we will leave you with an image of that evening’s supper. It was by far the best fish we have had in ages.

Home Ground

An Englishwoman, an Irishwoman, a Welshman and a ‘British’ woman were all sitting around their respective dinner tables having a Zoom meal. It was the time of the Rugby Six Nations tournament and the conversation between the Welsh and Irish contingent was animated, emotional, patriotic, fervent and loud. Suddenly Irish turned to English and asked why we didn’t exhibit the same degree of loyalty to England. There was quite a long, deep pause as we marshalled our thoughts.

While we are waiting, I will just mention that the ‘Briton’ present is so-called because she is linked by birth, domicile, emotional connections and genetics, not only to Surrey, but also to the Isle of Wight, Yorkshire and Ayrshire. In the interests of balance she is often pigeonholed as the token Scot, but on this occasion she adopted an English perspective (current domicile and birthright). As another aside, we are all white and British or Irish born.

Much of what came out of the pregnant pause will be picked up again in future blogs. I’m referring to things like never thinking we were the underdog, not having to fight for (in this case) Celtic identity, culture, language or independence; things like guilt over the empire (so often identified with the English if not, actually, factually correct); things like the adoption of the cross of St George by football fans; things like being economic migrants within our own country and having lost our roots or strong feelings of identity for a particular region.

The final question, from Ireland, was, ‘Well, where is home for you, and with what area do you identify?’ It was a sudden, light bulb moment for England. The answer is Kent. It is the land of my fathers (most of my mothers came to London from the Midlands). Kent is not known for its prowess in rugby, but it is where I instantly feel at home and is the only county where I don’t have to spell my surname.

As a child I visited deepest Kent regularly. We were allowed free range of the local countryside as long as we rocked up at our grandparents’ cottage in time for meals. Somehow, I absorbed an innate emotional, ecological, botanical, geographical, historical, architectural, cultural, literary, agricultural and (being Kent) horticultural afinity, and a deep appreciation of Kentish landscape and community. Many, many years later, on a visit to Hughenden Manor (which is in Buckinghamshire), we walked down an avenue of beautiful coppiced hazels. I instantly felt a warm rush of comfort and nostalgia for Kent. I instinctively knew their shape and form and what they stood for in the history of the Kentish landscape. You may think this is bizarre, but it was a wonderful feeling of coming home. Snowdonia does it for the other half of Terroir. So it’s not romantic tosh after all?

Coppiced hazels used as an ornamental avenue along the drive to Hughenden Manor

The hazel coppice, backed by the brick and flint wall, could easily be taken for a Kentish ensemble, rather than the entrance to Benjamin Disraeli’s home near High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire

This feeling was revived, when we went for a walk in a National Trust Woodland on the Surrey side of the Kentish border. No, we’re not purists; English Terroir feels pretty comfortable in Sussex and the Kent/Sussex/Surrey borderlands too, despite greater difficulties in surname spelling.

Walking into Hornecourt Wood feels like slipping on a favourite old glove and, in landscape terms, you instantly recognise every aspect of the history and ecology of the space around you. But you don’t have to be a local or an ecologist to appreciate the delicate beauty of a deciduous wood in spring. The wood anemones were at their best, low-lying but proud, massed but not in your face, stunning but delicate. The beefier bluebells were doing their best to catch them up and already a blue miasma was creeping over the ground, but the bridal wind flowers (Anemone nemorosa) were the stars of the show.

This is ancient semi-natural woodland, defined by being consistently shown as woodland from the earliest maps to the present day (1600 is taken as the starting point). At Hornecourt, it’s a southern classic: a mix of hornbeam which is easily coppiced to provide small ‘round wood’ for poles, fencing, hurdles and so on, and, at a lower density, oak ‘standards’ which grow up as single massive stems to provide construction timber. It’s been a while since that management system has been in operation in Hornecourt, and the hornbeams are growing bigger while the oaks are falling, creating a horizontal sculpture park, studded with their star-like roots. Even the occasional hornbeam has toppled over.

The sculpture park effect is also turned to vertical effect by many of the standing oaks displaying a spectacular range of burrs which are outstandingly visible in springtime.

The hornbeam is as delicate as the wood anemones at this time of year and their opening buds are hanging down like tiny, lax, cocktail umbrellas, while their catkins fatten, lengthen and release their pollen, to the disquiet of Terroir’s hay fever sensitive receptors.

Hornbeam bark is smooth to the touch, a simple garment, elegantly worn.

Hornecourt Wood isn’t all fairy glades, catkins and picturesque burr oak, however, and its topography hides some interesting and alternative evidence of former times. As background, you should know that the wood is just a small part of a large agricultural estate, donated to the National Trust around the middle of the last century; there are five main farms spread over three parishes. To a public which is used to the Handbook listings of heritage buildings and spectacular countryside, this is a side of the National Trust which is less well known. The estate is located in the farmlands of the Low Weald and the wood tumbles down a low escarpment to the sticky clays of the Weald below. A classic Wealden gill also tumbles through a steep-sided valley within the wood, and low-key plank bridges provide pedestrian access.

But there are warning signs of alternative or additional uses. It’s like stubbing your toe on a stone which shouldn’t be there. A rhododendron clump and a few cherry laurels are out of character; stands of birch regeneration, standing out like sore thumbs, have probably taken root in an area cleared but not restocked; there is the shock of an inner core of conifers, including what looks to me like western red cedar, a native of the Pacific coast of north America; new plantings of native hardwoods stand in regimented rows, even-aged and as yet un-thinned – the tell-tale tree shelters still lurking in the light-loving bramble undergrowth.

A quick chat with the National Trust confirms these findings. Apparently the wood was once managed for pheasant rearing – no doubt as an additional source of income at a time when local biodiversity was not sufficient justification in a working landscape. Pheasants are not lovers of draughty copses and the laurel may have been encouraged to provide cover and shelter.

The Trust experimented with ‘commercial’ plantings of conifers again, no doubt, following the practice of the time and chasing the available grants. Thankfully, they were limited to the interior of the woodland and the gill valley, no doubt to conserve the visual amenity of the ancient wood within the landscape.

Again, management aspirations and grant funding changed and much of the coniferous timber appears to have been felled to be replaced by native hardwood species, with the pioneer birch trees leaping in to colonise peripheral open spaces. No doubt the pandemic has entirely destroyed the timetable and budget for any plans to manage these young trees, such that they can integrate into the classic habitat which gives the rest of the wood its richness and beauty.

The National Trust has Terroir’s every sympathy. Woodland management is wonderfully rewarding on all fronts except financial. Until we can adopt a Natural Capital approach, whereby the ‘stocks’ and flows’ of natural resources and services can be assessed in monetary terms, and accounted for on a par with traditional evaluations of goods and services, mangement of magical places such as Hornecourt Wood will be an uphill (pun intended) struggle.

Terroir will leave you with two thoughts. The Zoom dining quartet (particularly the Celts) wish it to be known how much they appreciate living in England, despite their apparent fierce attachment to their mother lands!

Meanwhile those with a fierce attachment to their English forefathers delight in the sculptural impact of the historic remnants of a neglected, south east English, hornbeam-and-hawthorn hedge.

The Art of Lockdown

One of the inspiring experiences of lockdown has been the artistic endeavours of friends, family and colleagues, and it is with great pleasure that I have ‘curated’ (how posh) an exhibition of their works completed during the last 12 months. Some of the contributors have been creating artwork for many years, some only started in lockdown. All have been working within the confines of a pandemic. Many have sold their art at open studio or similar events, but the majority would probably classify themselves as producing art for the sheer pleasure of creativity and, for some, for the adventure of exploring their own artistry as a response to Covid-19.

The experience of curating turned out to be terrifying. I looked up the definition of the expression ‘to curate’ something, to see what it was that I was trying to do. Words such as select, organise, look after, present, interpret and display came up again and again.

Selection has been easy and involved emails to friends and colleagues who I knew were painters or artists. My brief asked for ‘something that you might have created over the last year which has some relationship to landscape, environment or society, however tenuous’. Thus the process of selection of the potential artists was down to me. The selection of the artworks, was (largely) down to the artists. I have accepted everything which was sent me. I was aware that some I contacted had been involved in portraiture but, knowing my background, they felt that the link to ‘landscape and society’ was just too tenuous; thankfully I managed to convince one artist that portraits are important too.

It was the requirement to organize, look after, present, interpret, and display which was so stressful. My own creative experience relates to working with actual, live landscapes. This can be onerous: the responsibility of creation must be taken seriously, and comes with responsibility to client, user and environment. But the curating or management of that landscape is also, in my experience, a joy which brings immense satisfaction. So why the tears and fears connected to this blog’s endeavours? One dictionary defintion continued: ‘typically using professional or expert knowledge’. Ah. So obvious. I am trained to handle landscapes which are alive in a biological sense and are physically anchored into our external environment (I can even handle the occasional house plant) but am a total amateur in curating artistic representations of and refections on ‘landscapes, environment and society’.

So, forgive me if I have made a poor job of exhibiting my friends’ and colleagues’ work. Not only am I inexperienced in presenting and displaying artistic output, but am constrained by the technlogy of a blog platform, on which my grip is tenuous to say the least. If admiration and enthusiasm were enough, then this would be a superb ‘exhibition’, but I know that in the curating sense this is not true! Please enjoy as best you can. My contibutors deserve better but I also know that, despite my ineptitude, their art will speak out for them.

Elizabeth Ellison

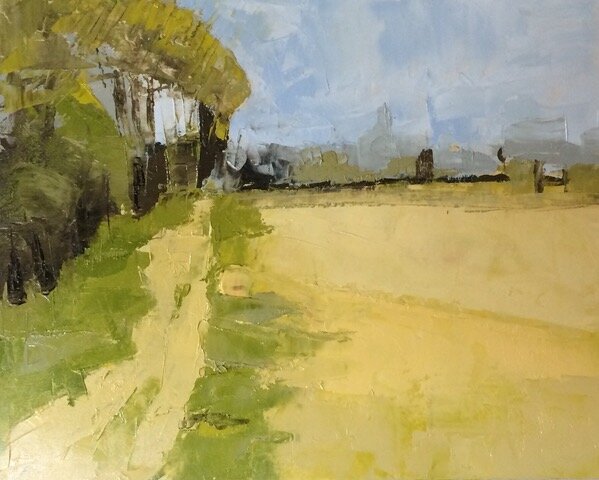

Regular walks started last year, usually walking up and over/under the A264, and the railway line, towards the farmland, and Rusper. I took photographs, (too cold to sit about) and resolved to paint small and fast, so no dithering or overworking. Found it helped to prepare sketches, mix all the paint first, and allow myself no more than 40 mins. Nothing too challenging or long term, but as they say, you have to put the paint on!!

Oil paint on board, palette knife

Size 24x18cms

Prepared throughout 2020

March

April

May

June

July

August

Carole

Instagram: @calligraphysurrey

I belong to a calligraphy group and last year the theme for our summer project was ‘CELEBRATE' and the format was a folded book made of a single sheet of paper. I wanted to use the letters of the word ‘celebrate’ but also wanted to specify what I wanted to celebrate. As lockdown happened about the time I started thinking about the project, I chose to celebrate trees, as they became my close companions during lockdown walks.

The large colourful letters spell tree names starting with the letters C E L E B R A T E and although I tried to use mainly native trees, a eucalyptus managed to sneak in.

The tree names were written first with a chisel brush and gouache paint. Then I folded the sheet of paper into its book shape and on each page I carefully wrote a different tree quote in pencil.

Gwilym Owen

I signed up to a lockdown art class, to do something, to motivate myself to attempt some art, and maybe to learn some new skills. I painted from photographs.

Fly Agaric Toadstool

Watercolour on paper

Starling

Water colour on paper

Stanage Edge, Peak Distict

Pen and ink on paper

Maureen Ford

Instagram: @maureen_ford22

Redhill redevelopment during lockdown. Charcoal drawing on paper.

The building site was a mass of linear, vertical, horizontal and diagonal lines and structures with contrasting tones. Having sketched the demolition of the Co Op store decades ago I couldn't resist taking multiple photos and sketching this view.

The painted version is executed using acrylic paint on paper emphasising the contrast of cold greys with the warm colours of the plant.

These are two of the portraits made during lockdown when Clive Myrie and Lesley Garrett engaged in fascinating conversations while sitting for Skye’s ‘Portrait Artist of the Week’ on Sunday lunchtimes. The portraits were fascinating, challenging and demonstrated a wealth of talent by participating artists who shared their work online. portrait artist of the week skye arts

Lesley Garrett, Pastel pencil on paper

[A Yorkshire phenomenon, ed]

Clive Myrie, watercolour on paper

Born on the ‘other side’ of the Pennines [ed]

Walking the footpaths and fields during lockdown and watching the seasonal changes to the fields brings a stability to the everchanging scenario of lockdown.

The sheep are moved to different fields when the foraging becomes scarce. Each sheep has a character of its own, be it curiosity or resignation.

Sheep in a turnip field.

Pastel pencil on paper.

Locked in or locked out?!

Reminders of a bright hot summer

Acrylic paint on paper

Zosia Mellor

I retired from practice as a Chartered landscape architect and have thoroughly enjoyed having time for pastimes. I really enjoy painting …! Before lockdown we travelled a great deal, however last year I did enjoy exploring different corners of England.

Landscape:

Darenth Valley in Kent

Fresh Food in Lockdown

Blackheath Farmers Market

: the market ran throughout both lockdowns and it was a wonderful outlet on a Sunday morning. I was struck by the vibrancy of the colours of this vegetable stall and the jumble of shapes and textures.

This painting is acrylic on board measuring 30 x 20 cms.

Field Mushrooms

: during lockdown walks for exercise I collected these field mushrooms. I enjoy painting seasonal subjects and lockdown has definitely heightened my awareness of the changing seasons.

I used acrylic paint on acid free card measuring 30 x 20 cms.

Rob Thompson

I wasn’t sure if I should include more of Rob’s work (see Blog 18 Cynefin), not because I was worried about over exposure (!) but because in my view he sells enough of his work to make him a professional. Rob thinks this is very funny. So Terroir has compromised and we are pleased to include some paintings he produced to support Snowdonia Donkeys, a charity dedicated to promoting human and equine health and well-being, through working and walking with donkeys. https://www.snowdoniadonkeys.com The two images below were created for, and donated to, a secret post card raffle. If you were generous enough to donate to the raffle and received either of the donkeys shown below, please let us know!

Before you go… thank you so much to all our contributors. When we started working on this blog post, Terroir had no idea just how rewarding, stimulating and throughly enjoyable this curating business was going to be. I hope you - our readers - are able to enjoy this lockdown art as much as we have.

… don’t forget to visit the gift shop! Most of the art shown above is for sale and, if you like their style, the artists also have a store of other treasures. If you are interested, contact Terroir at blogterroir.net@gmail.com and we will pass your details on to the relevant artist or atists. This aspect of producing art was never mentioned in the definitions of curating, and Terroir certainly didn’t embark on this project with this in mind. But, if any of our artists are starving in a draughty garret, we are very pleased to help!!

‘Chilly Finger’d Spring’

Spring - such an obvious name! So delightful that the English language settled on a word so simultaneously descriptive, self-evident and cheering. But there are other names, of course. Here are a few: vernal equinox, emergence, daylight saving, the start of British Summer Time, clocks spring forward, seed time, spring fever, primaveral, vernalagnia, frondescentia, repullulate, Chelidonian winds. No, Terroir’s vocabulary is not that extensive and we owe a debt of gratitude to a wonderful page on the BBC website: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/rMcWv9V1wWWNXxmbLkQW5P/12-spring-words-to-celebrate-the-new-season

Spring is also a time of religious celebration: Easter, Pacque, Ostern, Πάσχα, Pasg, A 'Chàisg, Cásca, Easter Tide, paschal festival, Pesach, Nowruz (Iran), Holi (Hindu), Vaisakhi (Hindu/Sikh).

Some aspects of spring are best avoided, however: gowk-storm (snow fall or gale which coincides with arrival of gowk or cuckoo - Scottish dialect), lamb-storm (spring thunderstorm at lambing time), blackberry winter (American spring cold snap). Again, thank you BBC.

More secular celebrations tend to get less exciting names: Easter holidays, spring break.

Terroir has spent many late winters watching for the signs of spring. We are not very good at phenology - the study of biological cycles and how they are influenced by seasonal variations - because we never keep proper notes. The only key information we can remember from year to year is whether the garden daffodils are out for St David’s day. 2021 qualified for an ‘only just’; one miniature bloom was sacrificially plucked for the Welsh lapel.

For some time now the old-fashioned enjoyment of a warm spell bringing an early clump of snow drops, or the traditional agony of a cold snap delaying the first pussy willow buds, has been tainted by the spectre of climate change. Phenology has become witness to a sad confusion of seasons and global influences. Watching the quickening of the local landscape from dormancy to a riot of activity is no longer the simple pleasure of our childhoods.

Lockdown, however, has changed our attitudes to spring even more thoroughly than climate change. And, so, this year we kept a pictorial record of our journey from winter to spring, from Christmas to Easter, from winter solstice to vernal equinox.

Our pictorial voyage is exhibited below, in fairly strict chronological order. We have broken it into three sections in accordance with our crazy, traditional calendar which does it’s best to ignore the lunar cycle, although the relationship between the moon and the earth is perhaps the most steadying influence in our currently topsy world.

January: a revealing month, showing details and patterns which are either hidden or overshadowed by the riots of spring growth, the ripening of summer or autumnal reveries. We found natural sculptures, spots of colour, fungus and seed heads, the loss of an old hedgerow tree veteran, extremes of weather and, yes, new life.

February: a month which started well but rapidly became the victim of strong meterological contrasts. The days continued to lengthen, but none of us in Terrior-land really noticed as the snow fell to a mixed reception. We - adult humans and nascent nature - bided our time until, finally, the sun came out again.

March: sunshine, cold and long. The gardens did their best to cheer us up, but the countryside held its breath, drab khaki beneath the yew, juniper and pine. Farmers and schools started work again, and finally, finally the rest of us were rewarded with green shoots, early blossom, thoughts of eggs and spring flowers aplenty. At the end of the month the sun came out and so did we.

“… for the choir

Of Cynthia he heard not, though rough briar

Nor muffling thicket interpos’d to dull

The vesper hymn, far swollen, soft and full,

Through the dark pillars of those sylvan aisles.

He saw not the two maidens, nor their smiles,

Wan as primroses gather’d at midnight

By chilly finger’d spring.”

John Keats Endymion Book IV

I think Keats would have hated climate change…

Happy Easter/Spring Break to you all. May the English and Northern Irish ‘Rule of Six’, the Welsh freedom to roam, and staying local in Scotland bring health and happiness.

Life and Death on the Fringe

The concept of the favourite aunt or uncle has always seemed a tad too sentimental for the likes of Terroir. We had no shortage of appropriate relatives. Between us we can muster seven uncles (of which four share our DNA) and twelve aunts (of which a mere five are genetically connected). The arithmetic is interesting, I agree, but multiple marriages (in sequence, we are not aware of any bigamy), plus an extra family lurking in the shadows, make for the usual complicated familial links. Some we never met, or even knew about as children. The known uncles and aunts were loved and appreciated but never promoted to ‘favourite’ status.

One set of relatives, however, has always generated an irresistible magic (one of Scary Great Granny’s daughters married into the clan – see Booth map blogs) and some years ago, I promoted a first-cousin-once-removed clan member to Favourite Cousin. No one could accuse Meg of being saccharine or a cliché. I first consciously met her when I was maybe six or seven years old, she in her early 30s, a tall figure in a beautiful summer dress. She knew how to engage with children - and also how to buy them presents. I still have that wooden jigsaw puzzle of the United States of America. I rated her as special from then on and was never disappointed. I hope she will forgive me for promoting her to ‘favoured’ status.

Last month, Meg died at the age of 92. I was uncharacteristically upset. The funeral was a Covid 19 limited edition, but with space for Terroir amongst the congregation of 30 max. The location was the Cotswold village of Ilmington, where Meg had previously lived for many years.

Why had Meg chosen Ilmington as her favoured terroir? It turned out that Ilmington had chosen her. A cousin (obviously not on the Terroir side, to whom such things do not happen) had left Meg a house in the village (a joint inheritance with someone else). Possibly scenting internecine warfare, the house was put up for sale, but the transaction later fell through. Realising the house was rather special, Meg and husband upped sticks, left the south east and moved in. They were right about the house and, fortunately, right about the village too.

Ilmington depicted on an Ordnance Survey map of 1897

The contours to the south west of the village rise inexorable up Campden Hill to the top of Ebrington Hill (731 feet above sea level). The gardens of Hidcote and Kiftsgate lie on the lower, western slopes of the hill.

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland' https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

Ilmington is described as a Cotswold Fringe Village. This seems to be an established typology, relating partly to geography (Ilmington is on the very northern fringes of the Cotswolds) rather than a derogatory comment on village character. It is also noted as the highest village in the Cotswolds and lies at the base of Ebrington Hill, the highest point in Warwickshire. I can bear witness to a certain draughtiness which becomes apparent when the sun goes in on an otherwise fine March morning.

Apart from its immediate attraction as a honey-coloured Cotswold village (however fringe), two specific things strike me about Ilmington. One is related to food and drink, and the other to architecture and buildings, both an integral part of any discourse on terroir.

Farmers have probably been cultivating the Cotswolds since the Neolithic period (from about 6,000 years ago) but Terroir’s sources of information stem from a slightly more recent era. Go to http://www.fabulous-50s.com/memories/oral-histories.html and you will find a rich seam of oral history called ‘Ilmington Remembers the 1950s’, inspired by celebrations for the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee in 1977. The stories are captivating, and revealing about post-war Ilmington life, which very much revolved around agriculture and its supporting trades and activities.

Two things stand out. During a time of continued food rationing, when other communities were still struggling to find a sufficiency and variety of nourishment, it appears that the village had plenty to eat. Gardens and allotments were the norm, obviously well tended and productive, even to the level of providing a suplus for sale (there is a mention of one family producing over a ton of potatoes in a year). Blackberries were foraged for eating or selling on. Meat was avalable - often in the form of rabbit, but a more traditonal Sunday roast did not seem uncommon and there was a butcher in the village as well as a grocer. Local farmers had dairy herds and there is mention of milk available as well as fruit for making puddings. No one seems to mention hunger, and many comment on having enough to eat.

The other recurring theme relates to orchards. Lots of orchards. There is mention of plums grown locally, but the product of the apple orchards seems to have made the biggest impact, with many farm workers reported as receiving considerable quantities of cider as part remuneration for their daily labours!

The maps below show that orchards were significant thoughout the late 19C and though to the interwar years of the 20C. Both oral history and mapping confirm the importance of the orchards in the early 1950s, but by the end of that decade, surveys show the bginning of reduction in area. The orchards today are sad remnants of their former glory, more so perhaps than even in Kent or Herefordhire. Some of Ilmington’s orchards are extant but derelict, others converted to alternative uses including housing.

Terroir has, however, just ordered some refreshment from a renewed interest in the apple harvest resulting from remaining trees, and we will report back on the apple brandy and dry gin in due course.

All map images reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland' https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

Satelite image of Ilmington today.

A new tree-scape now characterises Ilmington but it is still possible to pick out where the orchards used to be.

© Google Maps 2021

Railway gricer alert: check out the route of the Morton-in-Marsh to Stratford Tramway, a horse drawn system authorised in 1821 to supplement the canal system, and visible on both maps of eastern Ilmington and on the satellite image.

Terroir is in possession of another document relating to food, this time a substantial cookery book, produced in 1982 to raise funds for the Ilmington Church Roof Fund. I can still remember Meg flogging us a copy in a determined effort to do her bit.

We can’t find a single recipe with her name on it, but it is obvious that diets have changed a lot since the Cider with Rosie era of the 1950s. Bacon Jack, Back-bone Pie and Soldiers Cake are now heavily outnumbered by Tonille aux Pêches, Bermudian Banana Fritters and Sole à L’Indienne. I leave you to draw your own conclusions on the changes in lifestyle and demographic.

But I also mentioned architecture and housing, and those honey-coloured, marlstone Cotswold buildings. Unsurprisingly, Ilmington is a very attractive village (excepting the draughts). Unsurprisingly it is also heavily regulated. The Cotswolds were designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) (aka be innovative and outstanding before you even think about trying to build a house) in 1966. It was the 14th AONB to be designated and I’ve not begun to work out why it took them so long.

In 1969, nearly the entire village was designated a Conservation Area (apply for permission before you do nearly anything). When this designation was reviewed in 1995, there were 41 listed buildings or structures in the village (check your bank balance before contemplating modifications). Today, there are no less than 61 such listings!

An analysis of these buildings offers a fascinating insight into the agricultural heritage of ilmington and also to the extraordinary level of change which has occurred in the village since the 1950s. Out of the 61 listings, 58 are Grade II. Of these, I would suggest that over a third relate to the village’s agricultural heritage. No less than ten are described as ‘Farmhouse’ and the remainder are barns, outbuildings or cart sheds. Structures related to the religious life of the parish mop up another 10 listings, leaving less than 50% for other forms of residential buildings (which seem to range from cottage to Dower House) and the Chalybeate well head (see below). What a heritage. And, in case you are wondering, Wikipedia tells me that ‘Chalybeate means mineral spring waters containing salts of iron’.

As an aside, it is no surprise that this area comes very low in the England deprivation indices, with the main exception of ‘physical and financial accessibility of housing and local services’ (http://dclgapps.communities.gov.uk). Even in the 1950s, the oral history accounts often mention the wait for council housing, although it also records that such did exist in village. Today, private house prices in Ilmington are only slightly below typical prices in the south east commuter belt.

Only two buildings manage grade II*: the grandiose early 18C Manor House (think Doric Columns and a pediment on top to attic height) and the earlier 16C ‘Ilmington Manor with attached Barn’. The latter is much more to my taste, particularly because of the down-to-earth and very functional attachment.

Which leaves us with a single grade I listing, the Norman parish church of St Mary. This deserves a blog in its own right, but a mention of the embroidered apple map is essential. Created by resident June Hobson, the map is a copy of a 1922 plan which identified the locations of all the orchards in the village (https://www.cotswolds.info/places/ilmington.shtml). The church is also famous for its wood carvings by Robert Thompson (no known relation to Rob Thompson, the artist/architect, featured in the Cynefin blog, last month). Not only did he create the pulpit and pews, but carved his signature mice in eleven places throughout the church (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ilmington)

I sat in one of Robert Thompson’s pews last week, saying goodby to favourite-cousin Meg. Although she had temporarily left Ilmington (a decade in a life of 92 years counts as temporary in my book) to live closer to essential amenities in Stratford upon Avon, she had chosen to return to Ilmington for her final farewells and for her ashes to be interred next to her husband, in the church yard. It has been a great privilege, not only to have known Meg, but to have actually been related to her. A Grade I human being resting beside a Grade I Norman Church.

Privet Land

Although privet was an integral part of a Terroir childhood, it was many years before I realised the stuff had pyramidal spikes of white blossom, or experienced that heady, heavy, almost sickly perfume which emanates from the flowers. I suspect I caught up with the follow-on black berries even later. How come I was so ignorant of such basic aspects of this native shrub (Ligustrum vulgare)?

Flower image: © David Birch Privet flowers DSCF5484 https://www.flickr.com/photos/hedgerowmobile/328836044

Berries image: © versageek European Privet (Ligustrum vulgare) https://www.flickr.com/photos/versageek/1563369131

Like so many of us, I was a suburban child. The only privet I knew was the privet hedge which formed the boundary to so many semi-detached front gardens. In our area, Ligustrum ovalifoilum vied with Golden Privet (Ligustrum ovalifolium ‘Aureum’) for most-favoured hedge status. A 1950s and 60s summer did not hum with the sound of an electric lawn mower, but rattled with the sound of a push mower, and a pair of shears chopping the privet hedges into perfect vegetable rhomboids. No flower was ever allowed to appear on these hedges, so no whiff of potent perfume or tell-tale berries.

As a nearly-teenager I spent more time at the overgrown, more distant, end of the back garden. Here a neighbouring privet had been forgotten and run wild. Here I discovered the privet secrets of flower and scent. Such was the universality and uniformity of the sterile front garden privet hedge, that the shock of the fecund floral discovery was akin to finding out how babies were made!

My childhood privet landscape was one of inter-war, speculative, private housing development.

The urgent need for housing following WW1 created vast acreages of suburbia. The ‘Addison Act’ of 1919 and subsequent Housing Acts in the 1920s and 30s, ensured the construction of over a million local authority houses.

In 1923, the speculative builders of private houses joined in, adding a further 2.8 million ‘middle class’ homes. This was my domestic inheritance landscape: a ‘Tudoresque’, three bedroomed semi-detached, of brick cavity wall construction, with pebble dash and tiled roof, small front garden and bigger back garden. The house was fitted with electricity, gas, tiny kitchen, bay windows at the front, topped with a gable, French doors at the back, an inside bathroom and separate toilet. Two designs were often offered: ours had a curved bay and arched storm porch while Granny and Aunt J (Scary Great Granny’s daughter and grand-daughter - see the Booth Blogs) had a rectangular bay and matching storm porch. Subtle. Garages were an optional extra and ours had been built of asbestos but with the classic wooden double doors. Looking back, and looking at pictures of ‘typical’ spec-built estates, I realise that chez Terroir was at the smaller end of the size range; indeed my bedroom was not much more than 6 foot by 6 foot square.

From memory, the classic front garden featured a low brick wall, topped off with either looped chains or backed by the aforementioned privet hedge. By the 1950s, the uniformity was already being eroded. The low brick walls lasted well, but I have only faint memories of the looped chains and the privet hedges were definitely on the decline.

The images below are a classic selection of inter-war speculative private housing, in this instance as found in Terroir’s current home town. These all have the classic gable, over the two stories of bay windows, something which was missing form Terroir’s childhood estate. On the other hand, these tend to have a single, shared access to garages behind the houses. The density was often lower in the childhood estate, offering space for a garage beside the house, sometimes with a side passageway through to the backgarden, as well. Obviously, there have been significant changes to the front gardens, although low walls and hedges are not completely absent.

Since achieving some sort of adult status, Terroir had not given the suburban privet hedge much thought. Interest was revived recently, however, by the discovery that some of Sheffield’s allotments are surrounded by privet. We don’t mean neat, waist high hedges around the external site boundary. We mean that every two allotment plots are corralled within massive privet ramparts, at least 4 metres high and a couple of metres wide. Thankfully the plot sizes are generous, as nothing grows within the shade of these evergreen barbarians.

Now on constant hedge alert, we soon saw that the remains of privet hedges are alive and well. Not just in Sheffield but throughout the towns and cities of England and Wales.

Finding information on the history of the privet hedge has been tricky, however. Histories of modest 20th century domestic architecture are not difficult to find. But details of standard garden finishes, are much harder to track down. Were the looped chains a figment of my imagination? What sort of fencing was used to divide the residential plots? Was that front garden privet hedge a hangover from the 19th century or was it a purely inter-war feature? Why did Sheffield plant them around their allotments?

Some references we have found. Ian Waites, in his evocative book ‘Middlefield – A post war cou ncil estate in time’, talks of cut-throughs – ‘narrow channels of privet, wall and fence’ - where children would disappear and reappear as they crossed this Lincolnshire estate. The Municipal Dreams website (https://municipaldreams.wordpress.com) remarks that ‘The privet hedges remain a characteristic feature of Nottingham’s interwar council housing’ (Nottingham’s Council Housing by Bus and Tram Tuesday 19 June 2018) and ‘Some original privet hedges survive to mark the plot boundaries’ (Lincoln’s Early Council Housing 16 June 2015).

We will continue to research the history of the privet hedge but we would be grateful for any further information, whether circumstantial, anecdotal, or academic, which readers can contribute. If the comment box below is not visible, please click on ‘read more’, scroll down to the bottom again (sigh), and share your knowledge. We look forward to hearing from you.

Heavenly Bodies

What makes you choose one block of flats over another?

Location, obviously. And as an aside, the famous phrase ‘Location, Location, Location’ was not invented by Kirstie Allsopp and Phil Spencer, presenters of the eponymous TV programme, but by one Harold Samuel, property developer, in 1944. But then I expect you knew that.

Before lockdown, a good urban location might have been defined as a town centre, close to railway station/transport hub, shops, cinema, cafes and restaurants, for that authentic city experience; no car needed.

After lockdown, a flat may be the last place you want to live, the train station may no longer be relevant, parking may suddenly be more important and access to green space top of the agenda.

So how does a pre-Covid development of ‘luxury apartments’ sell itself? The one Terroir has in mind must have seemed a sure fire thing when it was planned in the 20 teens. It is literally opposite a good commuter railway station, right at the edge of the town centre, and with a cinema/restaurant complex, aimed at boosting the evening/night time economy, going up just across the road. Oh, and an international airport 20 minutes away (flight path not an issue). What more does the pre-pandemic, go-getting singleton or couple desire? The outdated sales blurb talks of good transport connections (well you will certainly get a seat on the train these days), retail therapy (currently closed), pubs and restaurants (if they ever re-open), and wonderful local countryside (true but car - and thus parking space – essential).

Terroir visited a two-bedroom show flat last summer. Considering this seems to be the most expensive apartment block in town, we were surprised to find: no separate kitchen (washing up in full view from living space); en-suite to master bedroom seriously reducing wardrobe space, no cat-swinging room in either bedroom, and a tiny balcony overlooking either a main road or the railway line (great for railway gricers, I suppose - see last week’s blog). Oh and we forgot to mention, and I quote, the

· Porcelanosa wall tiles in bathroom and en-suite

· Integrated Bosch appliances in the kitchen

· TV/FM Sky Q points to living room and master bedroom

· Stylish bathrooms with Roca bath and chrome Hansgrohe taps and fittings

Call us old-fashioned but we don’t understand a word of that.

So, lets go outside and take a look at the greenspace. On three sides the block is bordered by a main road, a sizeable but inaccessible railway embankment, and a second block of flats, still under construction. Out front? The building is separated from another main road (on the other side of which lies the under-construction-cinema site and the town centre) by an irregular space which has just been ‘landscaped’. We have to say, it did make us smile. And brought out the worst in us, too.

Let’s try to be positive, to begin with, at any rate. Topiary seems to be the order of the day, creating a green passage between the building and the main road. I love the way the cypress seem to flicker and dance like flames in the sunshine while the bay laurel ‘guard of honour’ keeps pedestrains on the straight and narrow.

But is it really going to work? I give it one summer to impress potential purchasers of the remaining flats (let’s stop calling them ‘apartments’) and by next year the maintenance regime will have started to ‘level down’ the whole thing.

Let’s take it apart.

The Cypress snake: these things grow fast and furiously. Keeping them in shape (literally) will take consistent and sympathetic trimming. Neither adjective is in common usage with the average commercial residential grounds maintenance team or, perhaps more accurately, the budget of the contract manager. The image to the right of the snake depicts a hedge of Cypress ‘Green Hedger’ which is cut back twice a year just to keep it in this simple form.

The conical bay trees (laurus nobilis): their natural shape is neither conical nor noble and they will need ongoing care and attention to keep them to this shape and size. The bay illustrated to the right of the newly-planted specimen grows in a garden about 500 m from our conical friends.

The yew bomb, cannon ball or heavenly body: so heavily clipped that we could not even begin to identify its species, so let’s assume Taxus baccata. Again, they don’t grow naturally like this. The Taxus baccata specimen on the right of the newly planted yew ball is neighbour to the non-conical and expansive bay tree, shown above.

The Euonymus (Euonymus japonica ‘Bravo’): no we are not expert Euonymus growers, that is what it says on the label. Already reaching for the sky, this shrub can, according to the Royal Horticultural Society, grow to 4 m high (yes, really) and spread to 2 m wide. And there are smaller varieties, so why use this one? The right hand image is a different variety but shows the same enthusiasm for vigorous growth.

The Mexican Orange Blossom (Choisya ternata) is no slouch and can quickly grow to well over a metre. It’ll be fun watching it fight for space with the canonball yew. And, oh horror, ‘they’ have included a Photinia fraseri (Little Red Robin). See Blog 3 (12th November) for why I dislike this plant so much.

I actually like the inclusion of Nandina domestica aka Heavenly Bamboo (it isn’t a bamboo, it’s in the Barbary family, most of which are types of Berberis). I’d like it even better if the contract supervisor had spotted the condition of some of the plants. Maybe they just haven’t done the snagging meeting yet… .

There are even a few trees, their trunks making a pleasant contrast to the other vertical elements which include flag poles and ‘for sale’ signs. At least these uprights will probably be removed in the fullness of time.

The choice of location did make us laugh, however. Some branches are already wrapped lovingly around a couple of lamp fittings and one tree is so close to the building that its juvenile boughs are making a concerted effort to climb through an adjacent window.

But there are good bits. A few cheerful daffodils (more would have been nice, of course), a herd of Bergenia (Elephants’ Ears), tough critters with cheerful flowers; they can also spread with alarming rapidity but only require brute force to get them back under control again.

I imagine, by now, that you are getting my drift: if left under-maintained, this formal and sculptual luxury apartment-selling landscape will quickly become a spectacular, if unsophisticated, jungle. Terroir has no problem with landscapes and gardens developing, and this particular landscape may well need changing, thinning, and/or restructuring to create a long term setting for the building. It needs to be both appropiate to the site (narrow, linear space, close to two main roads, plus heavy footfall between station and town centre etc) and to the management company’s budget. The problem will be if no-one manages the residents’ expectations, for when their cypress snakes and soldier bay trees, develop into common or garden trees and shrubs.

Walking the Line

As Chris Baines (environmentalist author and campaigner) once said, “Whoever heard of the Society for the Protection of Slugs”?