Smoke Signals

Railways have been a feature of our landscape for nearly 200 years. Like the canals, whose economic rationale they destroyed, the railways created massive feats of engineering, iconic architecture, and immediately recognisable structures and patterns within our townscapes and countryside.

The steam engine, with its semi-human characteristics – that chuffing heartbeat, the boiler door face - and the rails which so comfortingly limit its invasion of our world (but please don’t mention HS2) have also infiltrated every aspect of our culture. Literature abounds in railway imagery – The Railway Children (Nesbit), Anna Karenina (Tolstoy), Murder on the Orient Express (Christie), Night Mail (Auden). All of these have film versions but film-only classics include such wonders as Brief Encounter, Closely Watched Trains, and The Titfield Thunderbolt. Small boys collected engine numbers, Baby Boomers gathered at the ends of platforms with Ian Allan books, anoraks and shoulder bags. Model railways made clockwork, then Hornby 00, a household name and today, a visit to a heritage railway is a popular family excursion.

Of course, the end of steam in the 1960s changed the level of fanaticism, but the railway press still thrives, and many Baby Boomers still watch the railways, attend nostalgic railway clubs, and love to travel behind modern as well as steam locomotives. Environmentalists applaud the railways as a green method of transport and watch the conversion of fuel to hydrogen and batteries with interest.

Technology has also caught up with that most quintessential and picturesque of railway buildings: the signal box. But let another member of Team Terroir explain.

Individual railway company identity was always significant from the very start of the Victorian railway boom. Each company developed its own particular style, its stamp, its favoured colour scheme, and much remains of this heritage in towns and villages across the country. One distinctive building, however, is becoming much, much rarer, and that building is the signal box. Many have been demolished, some preserved, but only just over a hundred still perform the function for which they were built over a hundred years ago.

Early railway companies employed Police Constables not only to maintain law and order but also to regulate the movement of trains. They were there to prevent accidents. Train technology was in its infancy and accidents were commonplace. Constables were responsible for operating the signals and they can be likened to officers in Borough and County forces who performed point duty at busy road junctions, often operating road traffic light signals. When the time came that railway companies employed their own signalmen (and men they were), separate from the police, the nickname of ‘Bobbies’ remained.

As technology moved on, ‘remote’ signals were constructed, connected by wires to a specific signal cabin. And so the signal box was born, evolving from the 1860s huts and towers housing railway policemen, to a building housing the signal mechanism, and where the signalman could remain warm and dry during a lengthy shift.

As railways expanded during the 19th century, each station would have its box, sometimes two. Signalman needed physical strength to pull the levers which linked to interlocking rods and worked the points up to 350 yards distant, or linked to wires that changed the angle of the semaphore signals which could be up to a mile away.

Most of the work was in sight of the box, either in sidings and goods yards or, in busier stations, on through-lines and platform tracks, which all needed protecting to ensure no two trains found themselves on the same piece of track at the same time. In open country and on main lines, this usually required the building of signal boxes every two miles or so, all needing staffing, and provision of drinking water and coal (for heating).

Clear sightlines from the signal were needed, and space below for all the levers, interlocking and wires. Thus the signal box evolved for the most part as a structure not unlike a small two storeyed cottage with pitched roof.

The classic ‘cottage’ style signal box. The ‘cottage’ has large windows for good sightlines, and stylish ornamental roof details, which have also been used over the more modern toilet extension! The brick built box below contains the bottom part of the lever frame and the mechanical interlocking equipment, with wires and rods emerging at ground level to link to signals and points.

Below: a selection of classic signal boxes

Row 1 (Top row), left to right: Shipea Hill, Cambs; Littlehampton, W Sussex; Holt, Norfolk. Row 2, left to right: Kirkconnel, Dumfries; Brundall, Norfolk, Petersfield, Hants.

Row 3, left to right: Chartham, Kent; Ketton, Rutland; Park Junction, Gwent. Row 4 (Bottom), left to right: Dudding Hill, north west London; Woodside Park, north London; Ruislip, west London.

And some rather more quirky boxes:

Row 1 (Top row), left to right: Reedham, Norfolk; Selby, North Yorkshire, Knaresborough, North Yorkshire. Row 2, left to right: Goole, East Riding; Bopeep Junction, East Sussex; March, Cambs

Row 3, left to right, Boston, Lincs; Canterbury West and Canterbury East, Kent. Row 4 (Bottom), left to right: Hexham, Northumberland; Llanfair PG, Anglesey; Wylam, Northumberland

Technological developments have, however, remained a constant theme in railways as in all other forms of transport. From the 1920s, it was no longer strictly necessary for the signaller to have line of sight, as panels within the box would light up to identify exactly where the train could be found; (all that was needed was sufficient investment).

Architecturally, the 1920s amalgamation of the private companies led, on the Southern, to a distinctive art deco influenced design, called Streamline Moderne (below).

The Second World War led to reinforced flat roofs and brick build to remove the risk of fire from wooden structures.

When British Railways came into being in 1948, there were still over 10,000 mechanical boxes in existence, but the rate of technological changes increased rapidly. By the 1960s, just four modern boxes controlled all movements between say, Warrington and Motherwell, a distance of some 200 miles. And now, with digitalisation we are moving to an era of Railway Operating Centres (ROC), when, for example, a signaller in Cardiff controls the trains between Chester and the North Wales Coast.

Examine a railway map of the UK and one sees immediately that older signal boxes are now geographically peripheral. In England, go to Cornwall, to Sussex (Bognor Regis, Littlehampton, and Hastings, for example), to Kent (Deal, Sandwich, Minster), to Norfolk (King’s Lynn area), to Lincolnshire (Ancaster to Boston and Skegness), the Cumbrian Coast from Carnforth to Carlisle or north from Settle through the Pennines to the Scottish border.

Wales proves similar, with boxes remaining beyond Llanelli to Carmarthen, or Llandudno to Holyhead; Scotland, too: from Stranraer to Ayr, and along the coast from Dundee towards Aberdeen.

There are surprising clusters of boxes remaining however, for instance the line connecting East Anglia with the Midlands, linking Felixstowe and its container trains to the bulk of the country. Between Manea (west of Ely) and Frisby to the east of Leicester, there are no less than 15 signal boxes. It is not uncommon to find trains following each other every few minutes.

To stand near the Frisby box is to hear what seems like the continuous ringing of bells. Not for the signaller the song of birds, but brief moments of silence between either passing cars or warning bells. On this line the signaller is often hard put to note and respond to the rush of messages relayed from adjoining boxes.

Of all the buildings developed specifically for the railways, the signal box holds a special place as the railway artefact most instantly recognisable in the landscape. Signal boxes have become a staple of heritage lines, helping to recreate an idyllic view of England. Network Rail has also cooperated with Historic England to produce an inventory of over 150 listed boxes (some part of larger complexes), 86 of which are still used for their original purpose (https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/iha-signal-boxes/).

Nowadays, less than 200 working signal boxes remain, and by 2050 there will probably only be those boxes which control trains and boats on the Norfolk Broads, at Reedham and at Somerleyton. Or will a local group, determined to maintain their local heritage, ensure that those remaining today will still be there, a graceful or intriguing memorial to our railway heritage?

Image: North Norfolk Railway

An Autumnal Jumble

Two days ago, I received this photograph from the North Wales section of Team Terroir. The accompanying message read “Very late foxglove … maybe another blog on late flowering plants?”

Three journeys were precipitated by this idea. The first was a visit to The Moors (English Team Terroir’s local green-escape, and frequently featured in this blog). The second and third journeys circumnavigated Terroir’s gardens (one in north Wales and one in southern England). Like our modern climate, the results were confusing.

Let’s start with the gardens. Both had been frost free until the start of November. Both are fairly sheltered. Both have fairly similar elevations (the Welsh garden at 80 m and the English at 100m). Of course the Welsh garden is further north than the English garden, but also considerably further west, and only 20 miles from the sea. You also need to know that the Welsh team are the better gardeners!

Here is a sample of the late flowers in the Gardd Gymreig.

You may say that it is hardly surprising to have nerines or fuchsias flowering in the autumn, but in this garden, all the above have been an unexpected, if welcome addition, to the November display.

The English garden is less floriferous but the message is the same: we are surprised to see you.

The hydrangea heads are normally well coloured until after Christmas, but it is unusual to get a fresh bloom in November. The Salvia Hot Lips is technically a cheat, as it is cheering up the front garden of a neighbour, but the element of surprise is the same, although the profusion of flowers has probably been helped by the prodigious quantities of rain which have fallen recently.

Assuming that there would be an equally surprising range of flowers in bloom along the path through The Moors, Terroir set off in anticipation of a stimulating stroll. Unfortunately this assumption was utterly erroneous, and the herbaceous colour palette was based almost entirely on an array of green/brown leaves and seed heads. After some searching, a few late flowers were spotted lurking in the undergrowth (see below), and there may have been others even better hidden. Indeed, on turning back to take a better photograph of the single red campion flower, I was totally unable to find it again. Why this contrast with the exotics of the garden? We would appreciate comments and suggestions in the box at the end of this blog. If you can’t find it, click on ‘read more’ and scroll back down to fill in your thoughts.

The walk was not without interest, however. The variety of seed heads and berries provided a varied and sculptural and/or colourful display.

But it was the trees which were most varied and unpredictable. Considering that it is already early November, many seem slow to lose their leaves.

The English oaks were still in full leaf with plenty of late summer greens and only a few turning to autumnal yellow.

The American oaks which someone has planted here (probably Red oaks, see below left), were anything but red, having already lost many leaves whilst of a pleasant but unspectacular yellow/brown colour. The equally non-native Norway maple (second from right), which usually puts on a spectacular show of brilliant yellow at a bend in the path, is still green; the native field maple (below right) has gone totally autumnal.

The willows and poplars are a mixed bunch. The poplars (see below, upper row, left and centre) are either bare or have retained their upper most leaves. The sallows (upper row right) are still late summer green but their long leaved, weeping, cousins (lower row and immortalised in William Morris’ willow bough design) seem to have lost the plot completely .

The self-seeded forest of alders is largely denuded of leaves, but those with space to expand (below left) still retain their summer leafy glory. The dogwoods just seem to be confused.

Down by the laid hedge, the hazel has regrown vigorously and retained the enormous leaves which the wet weather seems to have encouraged. A neighbouring blackthorn , also in full leaf (below right), is clinging to a last remaining sloe. As with the holly, this year’s cornucopia of fruit has already been eaten.

Sadly, the chaos which is autumn 2021 feels like a metaphor for COP 26 in Glasgow. Already we have lost our ash trees (below left and centre: a dying ash and the lesion caused by ash die back disease). Is it too late to retain the stately beech (below right)?

Would the Tudors have switched off the lights?

How do we keep the lights on?

What did the Tudors ever do for us? I’m being England-centric of course, but I think most of us would suggest that they came up with a lot of important stuff. Apart from sectarianism, greed, identity politics, slaves, wars and so on, they also contributed literature, poetry, drama (albeit the bane of most modern school children’s lives), a debate on how to pronounce ‘renaissance’ and a whole clutch of modern historic novels.

A collection of 16th century talent. From left to right - Sirs Walter Raleigh, Philip Sidney, Edmund Spenser and Thomas Wyatt. Only Sir Thomas appears not to be a fashion victim.

As far as I can see, they also sustained a degree of complexity, intrigue, misinformation and complications which we would readily recognise today. I’m sure they would have handled the global nuances of climate change no better or no worse than we will attempt to do, this coming weekend.

But what started this train of thought? It all commenced with a day out in London and a visit to the British Library to view its ‘Elizabeth and Mary’ exhibition: ‘Royal Cousins, Rival Queens’ (https://www.bl.uk/events/elizabeth-and-mary).

Those Tudor complexities impacted on the day immediately. There are three Queen Marys in this exhibition - the eponymous Mary Queen of Scots, her mother Mary of Guise (Queen Consort to Scotland’s James V), and Mary Tudor (Elizabeth’s half-sister and Queen of England and Ireland from 1553 to 1558). We just about managed to cope with all this, but even our historian companions acknowledged the degree of confusion, as well as the need for transliterations of the Library’s very generous display of Tudor documents.

Staggering out, we came upon a different complication: where to sit to rest our weary backs and eat a much needed sandwich. When you find an empty bench, there is plenty of splendid stuff to look at, but the British Library is visually dominated by a sort of frieze or human tapestry of mini work stations all crammed with – presumably – students making use of the free electricity, free heating, free wifi and clean toilets, things which student accommodation may not always provide. No readers’ card is required for this area!

What does this cost the British Library? What is the benefit? I doubt this audience spends much in the café and nothing in the shop. It’s obviously popular but, although it is obviously valued, does it make sense in terms of energy consumption and carbon reduction?

After an afternoon spent in the wonderful carbon sink which is Highgate cemetery – a light canopy of ash with an understorey of grave stones – we ended up in the Sky Garden at around about dusk (https://skygarden.london/). This is probably a very good time to visit as London is beginning to twinkle whereas it is quite difficult to see the garden.

Yes, we were all underwhelmed with the design and content of the latter. A heavy dependence on Liriope, ferns and palms did not compensate for the prices at the bar. It appears static, uninviting, inaccessible, dense and dark. Perhaps it looks better in broad daylight but the photograph below right seemed to sum up the approach - a green background for the views of London and some expensive ‘hospitality’.

London-by-dusk, however, was a wholly different experience. The images, below, which range from south west to south east, do their best to replicate our - enjoyable - experience.

Top row: left - view down the Thames with Southwark Bridge, the Millennium Bridge, Blackfriars Bridge and Waterloo Bridge; centre - London Bridge and tower blocks; right - London Bridge station and the Shard.

Bottom row: left - HMS Belfast and City Hall; centre - City Hall and Tower Bridge; right - Tower of London and Docklands high rise

It’s spectacular, popular, and a real, capital city draw. One amongst us commented that when he started work in the area in the early 2000s, the newly completed Gherkin (centre of the image on the left), towered over all the surounding buidlings.

But it did make us ponder our carbon bank balance, and we will probably need to make some huge changes. The, ‘Oh it’s all right we’ll just use hydrogen’ perspective will, it seems, only make a modest contribution to the problem in the short term. So we are faced with compromises and decisions on what it is we value and what we choose to change or do without. Terroir is happy to live with wind turbines, for instance, unless and until something better can be organised. To us, knowing their contribution to ‘green energy’, is part of their human value in the landscape. Other’s would disagree, of course.

We enjoyed lit-up-London. Do we enjoy it enough to sacrifice something else so that we can keep the lights on, so to speak? We enjoyed the British Library experience. Did we enjoy it enough for the BL to keep the students and their laptops fired up, as part of that experience?

What would the Tudors have done? We’re pretty sure they would have kept the Tower of London. But we daresay they would have blown out most of the candles.

Arch 42

When does a connection become a barrier? A river, transporting goods from hinterland to the sea, is a serious barrier to people and goods who wish to cross from one side to another. Great for ferry operators of course and, eventually, great for civil engineers, when bridge technology caught up. Interesting that Thames passenger craft, with the exceptionof the Woolwich Ferry, now tend to go up and down stream rather than from one side to the other. We can be an adaptable lot.

Roads are another classic: as technology changes, so a cart track adequately connecting two market towns can develop into a roaring dual carriageway, blighting its environment and dividing communities as surely as a river. Again, good for civil engineers, good for online shopping and deliveries, but ghastly if you live close by, and dodgy if your best mate and local shop are on the other side.

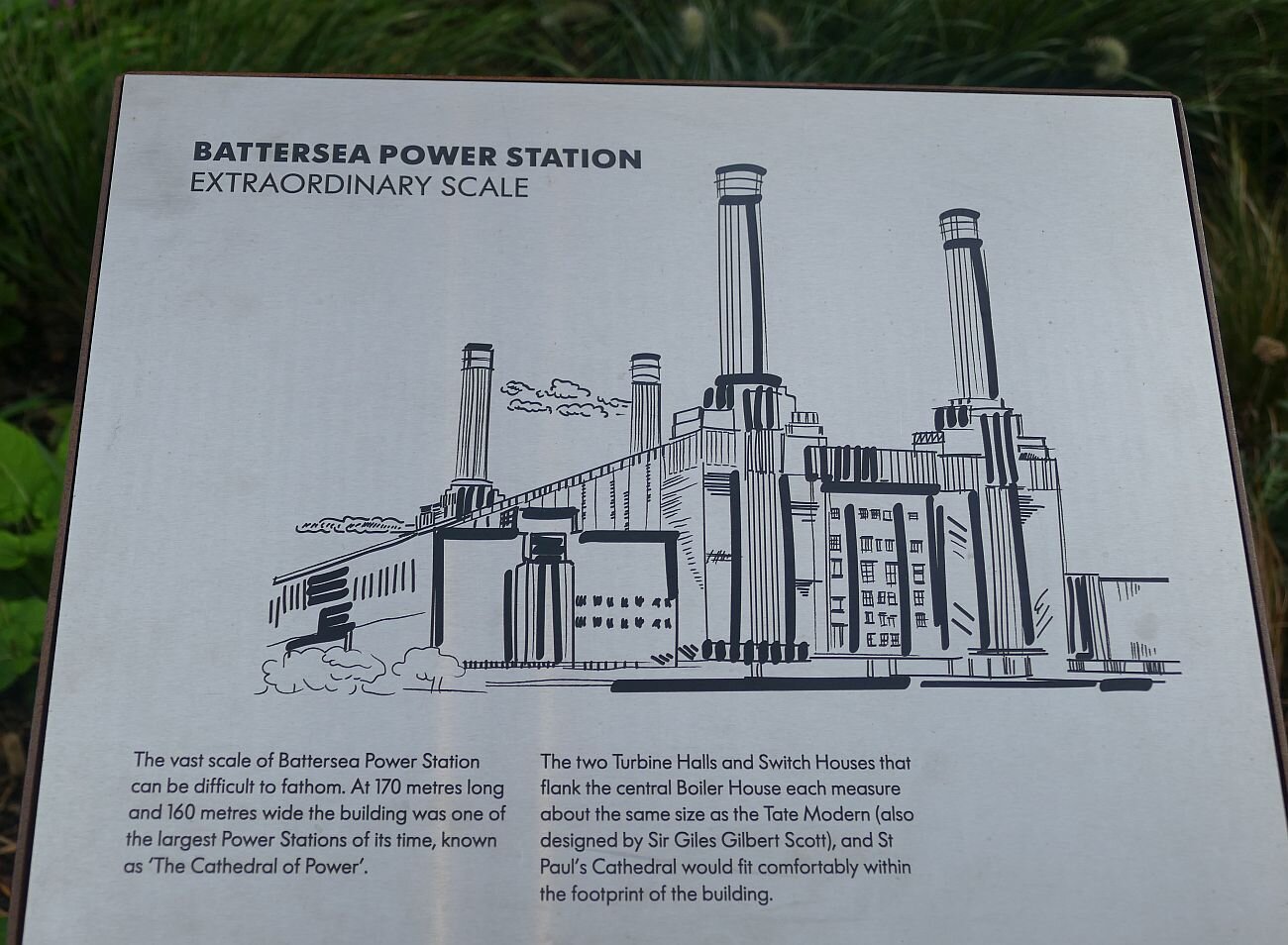

Terroir regulars will know that we recently visited an area of major urban regeneration, centred on Vauxhall, Nine Elms, and Battersea, on the south bank of the River Thames. Connections – mostly railways and bridges - have been major factors in the rise and fall of this former marshland.

Drainage seems to have been the first major technology to transform the Nine Elms area, followed by the economic impact of proximity to a major city, willing and able to buy the fresh fruit and veg grown in the developing market gardens. But, as in much of Britain, it was all change when the railways arrived.

An ambitious London and Southampton Railway, soon to become the London and South Western Railway, picked Battersea/Nine Elms as its location for the first ever London railway terminal. The neo classical station building was opened in 1838. Any modern commuter will shake their heads in wonderment at the choice of location, as anyone wanting to go to central London (and presumably that was everyone, unless your destination was the declining Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens) would need to complete their journey by road, or ferry from Vauxhall to London Bridge. The road journey via the London Bridge crossing would be about 3 miles; it would be even longer, and more expensive, via the local Regent (toll) Bridge.

In these conditions, it is not surprisingly, that things changed rapidly. Ten years later the station closed and moved to Waterloo and the Nine Elms site was developed into a massive goods depot, carriage/wagon works, and a locomotive depot. By the mid 1850’s other companies were interested in the area. The London Brighton and South Coast Railway soon joined the melee and other industry followed, as noted in the ‘Big House on the Prairie blog’. With technological changes, late 20th century decline was inevitable; by 1974, New Covent Garden was relocated to the area, but it was not until the 20-teens that serious regeneration plans were formulated.

Left: Ordnance Survey of 1913/14 'Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland' https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

Right: Google Maps © 2021

A significant objective of the regeneration project was to improve the links between the Nine Elms Opportunity Area and Central London, and to ‘create central London’s new urban district’. But, despite the demolition of the railway yards and all related industrial works, it was essential to retain the actual railway line, which must have become a bit of a thorn in the side of the regeneration project. Running right through the development area, the elevated line created a substantial barrier between Nine Elms to the south east and the American Embassy/Battersea Power Station area to the north and west. You can see the line running through the two images above.

Enter Arch 42. In railway times, Arch 42 was a stables, and later used by carriage fitters. Subsequently, the arch was taken over by a fruit and veg seller and then a mechanic. But the need to provide a strategic pedestrian access between Nine Elms and Battersea Power Station has now given Arch 42 a completely new role. You can now walk into it – and out again on the other side. The London Borough of Wandsworth are working hard on giving it some razzamatazz - it is as yet a work in progress - and there is a fascinating video on the development of this new, must see, railway arch at https://nineelmslondon.com/features/arch42/

So, please, join Terroir on a walk through London’s ‘new urban district’. We will walk from the newly opened Nine Elms Underground station, via the newly opened Arch 42, to the newly opened Battersea Power Station Underground station (see last week’s blog for our views on station naming). This is high rise land, so beware of a crick in the neck as we peer upwards at the unfinished townscape. Much of the green space has yet to be created so wear comfortabe shoes as there are currently limited opportunities to sit in the sun and relax. But there is the occasional cafe for a quick refuelling stop, although don’t expect economy prices.

Below: everybody wants to stress the area’s new connectivity.

Here is the new Nine Elms station. Next door was the site of the Vauxhall Motor Works, now a Sainsbury’s supermarket.

You may think you are moving from the old to the new, high rise zone, but low rise fruit and veg have been around the area since the 1960s. Note a last outpost of old fashioned housing, the rainbow zebra, fruity hoardings, the railway arches, the facade of one of the market buildings, market vehicles in the shadow of the new tower blocks and the railway line barrier, with the brave new world of apartment living beyond.

Moving on and, look, we are in Arch 42, looking back whence we came. Turn round and you will get a glimpse of where we are going.

Obviously, there is a way to go yet with finishing Arch 42 on the Nine Elms side. But on the Battersea side, a small landscape has been created to integrate the Arch into the existing urban environment. Obviously its very new, but we think the bug hotel is a great detail. Sadly, access has been only half thought through. Terroir photographer is standing (left) on the ramped entrance, but someone forgot the steps for those who don’t need a ramp. The ideal position would have been next to the sign post, particularly for the athletic types who approach from that end. Already, the desire line is being beaten through the planting (right) by those who opt to enter the arch by the shortest route - round the railing, through the planting bed, and finishing with a quick leap down from the retaining wall. We are not being over critical; we were only there five minutes and watched it happen.

We are now in Embassy land, a three dimensional landscape with serious, residential cliff faces all around us. We expected to see ravens and pergrine falcons at every turn. We were disappointed, but cheered by some minor attempts at using colour and detailing. We do not include the embassy in this critique, of course, but that can be found in the ‘Big House on the Prairie’ blog of two weeks ago.

As we turn westward, away from the embassy area and towards Battersea, we enter a zone of somewhat older building and a more mature townscape, full of cafes, residents and curious sculpture.

Here the streets and apartments have room for vegetation, some enhancing ground floor spaces and public realm, some more private but reaching vertiginous heights (centre and right).

Some is more traditional, ornamenting a private, ground floor, ‘off street’ patio (left), another climbs public steps in more a modern, airy design, while a third appears to be suffering from being placed in an apparent wind tunnel (right)!

The final landmark on our walk to Battersea Power Station station is the larger portion of New Covent Garden market, brightly coloured, large, unashamedly wholesale and commercial, but about to be dwarfed by more high rise accommodation.

But what’s this? A long, thin rectangular sign announcing the name of Battersea Power Station station? If you want to find out why Terroir is so amused by the discovery of this photograph (yes, it’s ours), you will have to read last week’s blog!

A Residential Power House

Last week we admitted that the opening of two new London underground stations had triggered a long overdue visit to the American Embassy and the Battersea Power Station redevelopment. Neither of the stations featured in the ‘Big House on the Prairie’ story but if you thought you had escaped a nerdy railway blog, we are afraid that you are about to be disappointed. There has been so much fuss and commotion in the press about the ‘Battersea Power Station Station’ that we thought we would take a look on our way to the eponymous new development.

To be honest, one of us was slightly disappointed. As far as we could see, there is not a single name board where the word ‘station’ is actually repeated. From all the media to-do, ‘one of us’ had assumed that this would be the case. On enquiry, ‘one of us’ has been reliably informed that roundel name boards do not normally include the word ‘station’. Nine Elms station roundels just say ‘Nine Elms’. And here is a picture of perfectly legitimate Battersea Power Station Roundel.

But the underground techies will tell you that the names on station portals, for example, do include the word ‘station’. See below for the Nine Elms example. But - and this is the bit that you might just want to stay awake for - close examination of BPS station reveals the complete lack of station portal signs. All we could find on the outside of the building were roundels, and they just said, ‘Underground’. Where are we? Moscow? Colliers Wood? No, there’s a socking great power station looming in the background; it must be Battersea. What a fudge. Embarrassed by having a station sign which says Battersea Power Station Station? Well, let’s just leave it off altogether. One of us is not amused.

Thankfully, a lot of trouble has been taken with the interior of the station (see images below), although one wonders how long it will last in its shiny, new, loved up, state.

And the exterior sets a new trend in underground stations in architecture as well as anonymity. Capped in un-burnished gold, the nameless station is set in a streetscape of grey and silver. Let’s hope it remains memorable once the helpful hoardings come down, or no one will ever find it.

As you emerge from Alexandre da Cunha’s dawn and dusk underground, spare a glance for some of Battersea’s pre-regeneration remnants, tucked between the hoardings and portacabins. Battersea Park Road (aka the A3205) is as unprepossessing as ever, and I wouldn’t want to be sitting on the road side balconies of some of the pre-existing flats, but the Duchess Belle Public House on the corner of Savona Road looks like a welcome - and well used - survivor.

Leave the main road and turn left into Pump House Lane. However cynical you are about the Battersea Power Station development, the wow factor slaps you straight in the face. The clutter falls away unnoticed and, as you walk up between equally bold hoardings, your gaze is held by the eye catcher sculpture at the top of the access ramp (image below).

Now we can understand, if not forgive, the sacrifice of the view of this fabuous building from the London to Brighton railway line which runs to the west of the development. Who cares about shoe-horning modern, residential highrise between the power station and the railway, when you can attract your potential buyers as they arrive at a smart new underground station or, terrible thought, by car.

Reality kicks in though, as Pump House Lane leads you into Circus Road East and around the southern end of the Power Station monolith. Modern high rise fills out the regeneration plot to the south west and west of the power station and light fades as you enter the canyon which is Circus Road West.

There are many details which attempt to make the canyon attractive at a human scale, but there is no denying that it is shady and that lower level apartments on both sides will also share the limited sunlight.

We enjoyed the current retail offer – a bike shop of course, the lettings office, natch and, best of all, the Battersea General Store. What a delight of chocolate, champagne, macarons and harissa mayonnaise. To do it justice, the store also stocked a well-known brand of salad cream and tomato ketchup. We checked the prices against shops in less prestigious locations and suggest Battersea feels it can command a mark up of at least a 45%. We were also surprised to see considerable merchandise aimed at children. Is this really a child-friendly development?

Street details did their best to lift the mood:

But the real delight is completing the journey through the canyon, and falling out onto the riverside. This area suggests a much more inclusive sense of fun - especially if you bring your own sandwiches.

Between the power station and the Thames lies an open space of quite unusual variety. Paving, water, seating, planting, grassland, quirky art work, industrial archaeology, picnic benches, fresh air, views and, of course the mighty river itself, complete with constantly moving water traffic, and the Battersea Pier as a water bus stop.

At the moment, there is plenty of space for all. The renovation and remodelling of the former coal jetties, where boats once delivered vast quantities of solid fuel to the power station, had only just been completed when we visited and this has added significant additional space and an abundance of picnic benches. It will be interesting, however, to see how this ‘play ground’ handles a considerably higher footfall (or ‘bumfall’ on those deckchairs) on a summer Saturday afternoon, when the residential blocks are complete. Maintenance will be crucial, of course, not just horticultural, but all the boring stuff such as litter picking, sweeping and cleaning, to keep it in the fresh and inviting condition which we enjoyed so much.

Want to live here?

Maybe not if you like to hide your dirty dishes and don’t want a view of an office block.

Big House on the Prairie

For many centuries Vauxhall, Nine Elms and Battersea were on the ‘wrong side’ of the river Thames. Today, of course, Nine Elms is home to the American Embassy and Battersea to massive, upmarket residential development areas. What went right?

If you were in the entertainment business, south bank Southwark and Lambeth had long been significant locations, beyond the restrictions and regulations of the City of London on the north bank of the Thames. Shakespeare’s globe theatre came to Southwark in 1599. Vauxhall had its moments in the sun in the 18th and 19th centuries, as the location for one of London’s largest and most spectacular Pleasure Gardens. The first such Garden to open (in 1729), Vauxhall finally closed its gates in 1859. “Simultaneously an art gallery, a restaurant, a brothel, a concert hall and a park, the pleasure garden was the place where Londoners confronted their very best, and very worst, selves.” https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/vauxhall-pleasure-gardens

Nine Elms had a shakier start – as marshland – and effective drainage was not established until the Heathwall river was tamed in the 15th century. Despite the subsequent construction of local roads, significant development seems to have been delayed until the Regent (later Vauxhall) Bridge was constructed in 1816, followed by the big one - the construction of the London and South Western Railway in the 1830s. London’s first - yes, really, first - railway terminus was opened at Nine Elms in 1838. For the next 150 years, the area from Vauxhall to Battersea would be dominated by railways, water works, gas works, industrial works and, finally, from 1929 onwards, the building and operation of Battersea Power Stations A and B.

Ordnance Survey of 1893/94 'Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland' https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

The regeneration of the Nine Elms area has created, “the largest regeneration zone in central London” and will include “new public squares, parks and footpaths created alongside major improvements to local infrastructure” https://nineelmslondon.com/transformation/.

An extension to the Underground’s Northern Line has also been constructed and two new stations opened last month, namely Nine Elms and Battersea Power Station. This event finally triggered a visit from Team Terroir.

Designed by American architects Kieran Timberlake, the embassy brief required the establishment of “a new paradigm in embassy design by representing the ideals of the American government—giving priority to transparency, openness, and equality” (https://kierantimberlake.com/page/embassy-of-the-united-states-of-america) while also creating a core element in the regeneration of Nine Elms.

Approaching the site through the ever increasing canyons of high rise residential development, the first glimpse of the embassy is startling and other worldly.

Three sides of the building are encased in a brise soleil, described as a “crystal-like ethylene-tetrafluroethylene (ETFE) scrim… Its pattern visually fragments the façade while it intercepts unwanted solar gain. The design of this scrim works vertically, horizontally and diagonally to eliminate directionality from the building’s massing.” https://uk.usembassy.gov/new-embassy-design-concept/

Terroir suggests that this last sentence would not win an award for crystal clear English-English or even American-English. One of us also admits to a first impression of a large number of mosquito nets hung out to dry. But there is no escaping the fact that the building is memorable, characterful and entirely unlike anything which has been, or is about to be, built around it. Even the massive gates which accommodate such workaday activities as deliveries and maintenance provide an airy camouflage to the larger access points. Sadly, the machine gun toting police officers who guard all entrances are a grim reminder of the real world; they look totally out of place.

The pediment of the building is encased in gardens and here the designers have created a landscape which is simultaneously legible, restful, encouraging, stimulating, and animated by people, wind and water. The key elements aim to create a reminder of the American prairies and Nine Elms’ wetland origins. Species selection, however, is in no way restricted to the North American prairies or southern English marsh and wetlands. Euphorbias and echinops nestle up to the more American rudbeckias, but are none the worse for that. The extensive use of swamp or bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) in and around the wetlands looks very impressive but this Louisiana native does raise a smile when viewed in the historic context of a Thames south bank location.

A light canopy of trees adds height, variety and contrast to the landscape. Autumn foliage will become Fall colour thanks to a collection of non British oaks and maples, those swamp cypresses plus the occasional gingko to add a Chinese dimension to the planting and colour palette.

Terroir is not the first to consider that the main water body looks suspiciously like a moat, and indeed the open grassland and mounding around the play area, plus the elevation of the building above the gardens, could be construed as a Norman Castle on its motte and within its bailey. Are those mosquito nets actually cunningly disguised arrow slits?

Our morning in the Embassy Garden was a pleasure. Security was obviously an issue but there were some very subtle touches too. We leave you with a boundary hedge, gently disguising a ram raid ring of steel.

Chalking up the Hampshire Downs

Exton to Buriton

We left you last week with a rant about the conservation of the chalk rivers of south and east England. It’s not often that one region of the UK has a majority share holding in a global ecosystem, but even this obligation does not always concentrate minds on the long view. The short term costs of treating threats such as water pollution can appear far more scary than the long term, and less tangible, benefits of a beautiful, clean, biodiverse, trout stream. These chalk rivers are capable of delivering oodles of human physical and mental well being, as well as significant contributions to the longevity of the planet. Conservation work is underway, however, the Meon Valley Partnership is a case in point. http://www.meonvalleypartnership.org.uk

Back at Exton it is Day 2 of our Hampshire Downs trek; the river Meon looks as stunning as it did the evening before, and the village itself amply fulfills the expectation of ridiculously pretty domestic, rural Hampshire. The pub looks just as shut, but that was our fault for arriving at silly times.

Easing our feet back into fresh socks and well-used boots, we now face 14 miles of extraordinary chalkland variety. The map suggests considerably more woodland than Day 1, but only hints at a number of surprises which the walk has in store for us.

Old Winchester Hill was the first climb of the day and delivered bountiful rewards. The National Nature Reserve was stunning in terms of habitat variety - wild flowers, scrub, grassland - and abundant butterflies and other invertebrates. Above us, hang gliders caught and spilled the breeze and the rampart of the iron age hill fort appeared to encircle the hill top with a green choker.

The tapestry of agricultural landscapes which accompanies this section of the South Downs Way is exceptionally varied, but sometimes farming just will not pay the bills. Business diversification may become essential, when attempting to create new revenue sources from the capital land resource.

Below Old Winchester Hill, we found some classic examples of new uses for old buildings, and new incomes for under-earning land - and water.

A farmyard converted to art …

… and an old estate embracing fishing and glamping.

The second climb of the day, from Coombe Cross to the top of Wether Down (234 m), made Old Winchester Hill seem like a stroll in the park. Here the atmosphere was very different. This is Hang Gliding heaven and home to a variety of airborne gadgets and enthusiasts, as well as a trig point and a collection of communication masts and support gear.

The track down is hard and stony, like so many sections of the South Downs Way, and deposits you in an ingongruous mix of former MOD land, redundant razor wire, a small holiday complex and a new estate of sumptuous residences, each set in a garden the size of a couple of paddocks. Time to move on.

The Way now approaches Hyden Wood, a substantial mixed woodland with some spectacular beech stands which give respite to the eyes and a lift to the heart. But once again it is hard on the feet (none of that soft, North Downs mud), and the next couple of miles are all forest track and country lane. Clean for the boots but tough on the joints.

We also know what is coming next - the Queen Elizabeth Country Park, renowned for its gradients. The Way spares us all but the flanks of Butser Hill (remember that top height of 271 m?) but the track surface and the view on the way up that flank, are somewhat unpreposessing. Imagine the relief, therefore when we emerged at the top of a wonderful, grassy slope, which launched itself down the incline, calling out for us to follow. Better on a mountain bike, of course, but wonderful on foot too. Unfortunately, there is a tarmac snake lying in wait for us at the bottom of the valley. Just as we had to negotiate the M3 on our way from Winchester, now we have cross the A3 to attain the final ascent of the day, through the Queen Elizabeth Forest.

After the heady environment of the grassy slope, the search for the A3 underpass is a real anti-climax. Downland turf turns to urban concrete and the noise levels are rising all the time. We hurry through the underpass and enter the thickness of the forest, expecting an enveloping peace to fall at any moment. But the Way lies parallel to the dual carriageway and the constant, yammering roar of massed internal combustion engines follows us for nearly a mile.

Finally the clamour fades as we begin the long plod up the tree-encrusted chalk of War Down, tired now and tripping on the flint and tree root track. Cresting the last rise, we tip over the edge of the down and into the welcoming arms of a car park, complete with waiting back-up vehicle. We don’t even have to walk off piste to reach Buriton village but are driven straight to the pub.

We have completed the 1987 extension of the South Downs, from Winchester to Buriton. The next stage will take us to West Harting Down and into Sussex. But we will keep that for another time.

After a long draft of St Clements, even the main occupant of the pub car park can raise a smile.

South Downs Way - the Hampshire Downs

Southdown thyme: “ ’You don’t get nothing like that in the Weald. Watercress, maybe?’ said Mr Dudeney.”

Rudyard Kipling, Rewards and Fairies

Last winter, Terroir relatives, while battling with Covid Cabin Fever, announced that they were going to walk the South Downs Way, from west to east in September 2021. Would we like to join them? We said we would.

Given that a lot of us think we know what to expect of the South Downs Way, it is surprisingly unpredictable and idiosyncratic. Is it similar to the North Downs Way? No. Well, that’s that one out of the way. You want detail? The South Downs Way has less mud and a whole lot more easy-to-reach seaside.

But both chalk ridges share some basic characteristics which are significant in the development of the ancient network of tracks and paths which underpin the modern long distance trails. Chalk drains freely and is easier to clear of woodland than the heavy soils of the clay Weald lands and a pastoral economy, based on sheep, is feasible. The chalk ridges also provide height (North Downs top height is 294 m/963 ft on Leith Hill and South Downs 271 m/889 ft on Butser Hill). This provides great visibility if you feel threatened, need to build a fort or just want a great view of the Isle of Wight or London.

Kipling’s 1910 story, ‘Rewards and Fairies’, illustrates the ancient tensions between the “messy trees in the Weald” and Shepherd Dudeney’s “bare, windy chalk Downs”. If you want a feel for the contrasting magic of the chalk lands and the clay Weald, ‘listen in’, as the children Una and Dan do, to the discourse between Puck and the ‘half naked man’ (The Knife and the Naked Chalk).

By the latter part of the 20th century, the need was felt to understand and conserve landscapes, resulting in the National Parks movement and creation of Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The development of the Sussex Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) and the South Downs Way (SDW) were understandably interwoven. The trail was approved in principle in 1963, the South Downs AONB established in 1966 and the SDW finally opened in 1972, linking ‘chalk’s end’ Eastbourne, in East Sussex, to the village of Buriton in – shock horror – not West Sussex, but just over the border in Hampshire.

With the increasing rumble and ground swell to turn the Sussex Downs and neighbouring Hampshire Downs AONB into a National Park, the two Natural Beauties transformed into Conservation Boards and Joint Committees until they finally metamorphosed into a single South Downs National Park butterfly in 2010. The South Downs Way was already there; it had been extended from Buriton to Winchester as early as 1987.

Apart from the dry walking conditions (of which more anon), the South Downs Way is also unusual amongst National Trails for being largely bridleway. It is hugely popular with cyclists to the extent that alternative routes and walker-only sections have had to be invented. The Way is extraordinarily well signed but anyone who is poor on pictograms or colour blind could find navigation a nightmare.

Terroir had been pottering around the Sussex end of the SDW for decades, either section-walking or incorporating lengths into stunning, downland circular rambles. Access can be surprisingly sustainable, with careful use of trains and – the increasingly infrequent - buses. We seldom go the extra mile(s) to the western, Hampshire end, however, so we elected to join the walking party at the beginning of the expedition and hike from Winchester to Exton, and then Buriton. Here is the expedition story.

Winchester to Exton

The support team dropped us in Bridge Street, central Winchester, where the starting point, a silvered wooden block, buried in Salvia ‘Hot Lips’, lies outside the City Mill and, possibly more importantly, a cafe (both closed when we were there!). Illustrated at the top of the Blog, the block’s spiky, orange ‘hair cut’ actually represents the alarmingly exaggerated path gradients which await us.

By necessity, the first mile is urban, but no one can argue with a stroll along the River Itchen, before a short amble through some embarrassingly mixed, Winchester-fringe, architecture. The initiation ceremony continues with a hellish crossing of the M3, but despite feeling like prisoners, we survive and emerge, relatively unscathed, onto gently undulating chalk farmland. A classic, chalkland, fruiting hedgrow completes the PTSD healing process (despite a certain urban fringe unmanaged look), with massed privet, hawthorn, blackthorn sloes and rose hips.

Two things struck us about the day’s walk. The defined chalk ridge which characterises the Sussex section of the Way, is lacking here and reminded me more of a domesticated Salisbury Plain, than the South Downs. The northern-based members of the party also commented on this rolling plateau/valley combination rather than the chalk scarp-and-dip slope with which we are all more familiar.

The second factor which particularly struck the south easterners is the large scale of the agricultural landscape and its accompanying architecture, in comparison with the far smaller and more vernacular domestic buildings of the villages and outlying cottages. To us, it read as though the villages had retained their pre 20th century quaintness, while new infrastructure (piped water, drains, electricity etc) had eliminated draughts, leaky roofs, smokey kitchens and outside privies, and 21st century maintenance techniques had retained and enhanced the charm and beauty of a former era. Meanwhile, agriculture had, with a few exceptions, moved forward to embrace much larger scale operations, with vast fields of wheat, barley and oilseed, plus massive investment in machinery, in additives to keep the thin chalk soils producing, and in massive, functional buildings to support the whole operation.

Upper row: the domestic and vernacular. Lower row: the changing scale of agriculture

As we moved eastward we did re-discover grassland as the slopes steepened around Beacon Hill. Some was ranch-style improved pasture, bright green with fertiliser, but other areas supported the dull greens and browns of more diverse meadow, and verges fulll of wild flowers.

The final walk, down Beacon Hill towards the village of Exton, was enhanced by the anticipation of a pint well-earned (even across all that improved grassland - above, far right). Earned, maybe, but delivered? Nope! The pub had just shut! But here was the River Meon, flowing through the heart of Exton as the Itchen flows through the heart of Winchester. These crystal clear, chalk rivers are not only beautiful, but extremely vulnerable to pollution including chemical runoff from agricultural land. Of the 200 or so such rivers known of globally, 85% are found in southern and eastern England. That is one heck of a responsibility which we are currently not addressing as well as we should. https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/habitats/freshwater/chalk-rivers

Below: Exton and the River Meon

Next week: Exton to Buriton

A Landscape of Ill health

I never thought I would write a blog like this.

This one is very personal, although the landscape of ill health must be an environment which has been familiar to many of us at one time or another. Whether it’s man ‘flu, measles , or malaria, the landscape of ill health is the context in which you start feeling ill, seek help, sweat it and, hopefully, start to recuperate and/or adapt your lifestyle to make management easier.

I can understand if you don’t want to read this blog - it’s a strange and sensitive topic - but I felt I needed to record where I had been, during a recent bout of ‘ill health’ and what, if anything, had helped me along the way.

The journey started in the floriferous garden of a friend. Already strange pains were running around my insides and I didn’t have the energy to wander around the abundant and colourful beds, but sat in the sun soaking up the ambience. We left after an hour and went home. By 8pm, we were in A&E.

The entrance to this particular A&E isn’t easy to find but the hospital has painted the most visible outside wall a bright, bright shade of red with the word ‘EMERGENCY’ painted across it in white. It works. It is cheerful, simple, informative and actually makes you feel rather important.

Inside, the waiting area is high-ceilinged, a cross between a modern church and a barn, with serried ranks of chairs drawn up below. I could see no pictures on the wall, or few helpful notices, apart from an electronic information board presenting ghastly statistics on how long your wait was likely to be. Hell probaby has boards like that (‘five hours to the boiling oil cauldron’) and the uplift from the red wall outside vanished immediately.

The waiting area chairs are unappealing, too, with their straight lines, which does nothing to make the intermittent scatter of uncomfortable people look more homely. There are as many, sometimes more, healthy companions as would-be patients, so it’s difficult to gauge the actual numbers. The worst aspect of the chairs is the occasional armrests which make it impossible to lie down. I assessed the floor. No, I would just fidget, moan and wander around.

Across the floor lies reception and the nurses’ station, with security guard sitting at the back. The nurses are efficient, competent and understanding. It looks professional and, most of the time, unintimidating. A real boost to the patient. Every time I took a pain relief amble, I was immediately asked if I was ‘all right’ (I knew what they meant) and then they reassured me that I was first on the list for triage. I appreciated this, of course, but there is no information on how long the patient in front of you will take to pass through the exit doors of triage heaven.

Just as I was thinking that I could stand the wait no longer, my name was called. As I stood, I noticed another couple had also got up and would get to the Triage door before me. They slipped through and the door slammed in my face. Pathetically I knocked and hoped for reinforcements, but finally the door reopened and the ‘other’ couple were politely ushered out. We were in!

The triage room was large and clinical, which was fine, although I felt as if I were being auditioned rather than assessed. Next call was a blood test and we passed into the medical back-of-house to start on another, and hopefully therapeutic, journey. This area reminded me of an Arab Souk or a medieval market, with small booths for particular specialists or purposes and other areas where people, desks and equipment spilled out into the main market place. This layout seems to have served humanity well for hundreds of years.

We progressed further to ‘find me a bed’, which turned out to be a consulting room couch in a small space with a glass front wall. Here I was put on a drip and plugged into a bag of painkiller. A sensible doctor arrived and so, eventually, did a couple of boxes of useful looking pills.

We were discharged around midnight and struggled to find our way out of the medical souk, locate an exit door and, finally, find the car. The car park cost us £5; this would have been free in Wales or Scotland. We could afford to pay, but even in my befuddled state I felt that others might consider this a real hardship. Yet without that car park revenue stream, the Welsh Health Service seems to be doing as well, if not better than the English. Has England missed something?

Just before 2 am, we were back. Sadly, nothing had changed - for me or the hospital - except that there were fewer patients by then and a shorter triage queue. There was a wrangle about whether I needed another blood test. No-one took a decision so we carried on anyway, to find a ‘bed’. This cublicle was even smaller - like a very down-sized version of a French Formula 1 hotel (or, possibly, a cell). Space for just a ‘bed’ and a chair, with toilet ‘across the hall’.

Between fitful bouts of sleep, we made room for another drip (water - thank godness - and an anti-sickness drug) plus a couple of codeine pills for good measure. By 5 am nothing much seemed to be happening so we decided it was time to get out. It was mentioned that this might not be a good idea. ‘You haven’t been formally discharged’. We looked at each other. An Anglo Saxon expletive hovered, unspoken, in the air. A form was signed. We were going home. And, once we found a ‘way out’ sign, we were going in the car, parked in an ‘unofficial’ but free space.

Once home, the landscape becomes comfortably familar, but limited. From my bed, I can’t see out of any of the windows. The ceiling is less than stimulating and not even the geraniums on the wall can inspire any kind of emotion. Rumpled bed sheets aren’t attractive either but for the first twenty four hours I am mostly asleep and don’t care. From then on it’s the solace of home which matters.

The bathroom is still ‘across the hall’ but there are only two of us in the house. The bed gets made, the floors are hoovered.

Although I may not have cared about the bedsheets, I was disturbed by a new landscape, which now accompanied me, created entirely within my slightly delirious head. If I closed my eyes, a collage of beautifully formed images emerged - buildings, views, people, letter boxes, cats - there was no end to the show. As I lapsed slowly into sleep my brain told me stories so real that I raised a hand to take a pen or open a box. Only to find the images were not there. Then to find that my hand never actually moved either. What had triggered in my brain to take this extraordinary action? Although not threatening, I was glad to wake today with only an external landscape to navigate.

Finally, I was booked for a scan at the local surgery. The ambience in the waiting room feels much more communal. The ceiling is lower but not claustrophic. The chairs break ranks and curve around and across the room. There are lots of relevant and friendly notices and posters which creates a positive vibe. People come and go, creating life and movement. Looking at an annoucement that three practices are now working in a group, we were struck by how this reflects wooded Surrey; the key words in each surgery’s name are ‘Woodlands’, ‘Hawthorns’ and ‘Holmhurst’. But best of all, the large plate glass window lets in the sun and I can see the nodding heads of ornamental grasses, blowing in the wind, just outside.

Shall I go back to bed? No, I think I feel strong enough to watch a little television and look out of the window.

A Contested Landscape

Part 2 - Enclosure

by Keren Jones PhD, CMLI, Dip LA (Glos)

The next great milestone in the Shropshire story of conflict over land and property was the Tudor dissolution of the monasteries. The first parish records of 1536 record there were around 800 religious buildings in England and Wales, yet four years later there were none. For those of us with an interest in all things landscape, the dissolution was to ultimately be a mixed blessing as it also marked the birth of the English Garden, and with it, the birth of what was to become, much later, the landscape profession. As demolition made land available for large, new country houses with large parks and deer enclosures, the new landowners were often absent or did not need to earn a living off the land. This meant that adjacent land was often put to aesthetic uses, rather than being cultivated. These changes proved to be a mixed blessing for my Shropshire family. Those wedded to the old ways lost out as their rights to common land were eroded, but other members of the family gained new employment on the grand estates.

Various branches of my family lived on the summit of Brown Clee and became known as out-commoners. In exchange for the rights to grazing, cutting turf and collecting wood, they would have been subject to a modified form of Forest Law, which meant that they were not allowed to disturb deer that ate their crops.

They had to follow very precise routes, known as Straker Ways, from their homes to the grazing areas on the Clee. Many can still be traced as sunken or hollow ways. This was the way of life that was now at risk.

What began with the Tudors and Dissolution, escalated after the Civil War. Although the war had impacted on and divided communities and families across England, it was the subsequent fight between rich and poor over land enclosure that was to have a lasting and permanent impact on people, place and nature. Initially Shropshire was less affected by the Land Enclosure Acts, because of its pastoral nature. Since the 1600s any enclosure of arable fields had been mainly achieved by stealth, as a farmer bought out rights. Matters became contentious, however, when the remaining stretches of moor and marshes started to be enclosed. These areas were subject to over 70 different acts, and as a result many landless squatters became homeless.

My Brown Clee ancestors were amongst those who had to fight for their rights when, in 1809, a local enclosure act was focused on the common land around nearby Stoke St Milborough. The Lord of Earnstrey, tried to obtain extensive allotments on the west flank of Brown Clee, including rights to a Royal Forest.

Earnstrey’s actions had an impact on many small holders and landless labourers, but the commoners’ resistance meant that common land on the Clee Hills still remains today, even though it is not as extensive as it once had been.

On the other side of Brown Clee and the Earnstrey Estate, lies the Burwarton Estate, still one of the county's largest private estates not open to the public. In the 18th century it passed to Viscount Boyne who created an Italianate House, formal gardens, pleasure grounds and an extensive landscape park, all sited to take advantage of the rugged upland scenery. At the time, my great, great grandfather was a young boy living in Burwarton, and very likely became part of the gardening and construction force. He was the first known gardener in our family.

His eldest son, my great grandfather, also learnt to work the land from a very young age, developing skills as a gardener at the Dudmaston Estate, near the River Severn south of Bridgnorth, and within the remnants of the ancient Royal ‘Forest of Morfe”.

But the world was changing. Industrialisation was spreading its tentacles from what was to become the Birmingham and the Black Country conurbation. My great grandfather would have seen the first steam trains hurtling past Dudmaston making their way down to Bewdley.

Then in the 1880s - having lost his wife to tuberculosis – the struggle of making a living in the place that had been our family’s home for generation became too much. He left his two children with family relatives, and broke the pattern of living off the land to start a new life in Middlesex.

Nick Haye’s ‘Book of Trespass – Crossing the Lines that Divide Us’ looks at all the contemporary issues which have developed around land and boundaries over time. He finishes as I will, by dwelling on what he calls the alternative stories that threaten the established land histories. These alternative stories are “the stories of the commons, folk stories, the stories that come not from the castle but the plains, the collective voice of the people … these are the stories, that consecrate an alternative story of the land”. (Nick Nayes, 2020).

In this spirit, I want to finish by touching on an extra layer of richness in this local landscape and community narrative that my family would have shared and passed down through the generations. For Shropshire hill country is the land of giants, fairies and witches. Folklore is rooted in the landscape. Here is just a couple of the many myths and legends:

Long, long ago when the earth was new there were two giants looking to make a home. When they found Shropshire they decided to create a large mound where they could live and see for miles around. However, the giants that lived here fell out and threw stones at each other across the Clee Hills.

Later, when the young Saint Milburgh from Wenlock Priory, fleeing from a pursuer, fell from her horse on Brown Clee, a new holy spring appeared on a site where she fell. It gushes with water to this day.

These stories that combine historical fact and community myth and legend shape how we relate to the landscape, as well as what we see when we visit. By studying the past we can gain a better understanding of why it is as it is, what is important about the landscape for local people and also perhaps better appreciate that what we see is not as idyllic, equitable or sustainable as it might seem at first glance. In so many ways the landscape I have learnt to love epitomizes the view of Anne Whiston Spirn, in her book ‘The Language of Landscape (1998): “Landscape is not a book to be read once and thrown aside, for not only does it have a new story to tell everyday, but it has many stories.” This blog captures a mere few of those stories which I have had the pleasure of discovering.

What next: My journey of discovery started over ten years ago with collecting and archiving information, records, letters, photographs and any other snippets of material I could get my hands on. Some argue that this act of archiving is akin to the folk art of quilting:

"Like quilting, archiving employs the obsessive stitching together of many found pieces into a larger vision". Goldsmith K, 2011, Archiving is the New Folk Art, Poetry Foundation, 19 April, 2011.

I feel that now is the time to tell the stories which I have discovered. I am immersed in the process of creating a book series, entitled ‘Archives to Art’. It has become six stories, one for each of my grandparents, and a fifth which is about their relationship with land and landscape. There is also sixth story which is intertwined through all of these, and has emerged, unexpectedly. It is the narrative about my own journey - exploring the details in the archives, visiting places and talking to people - and turning archives into art.

A Contested Landscape

Part 1 - Invasion

by Keren Jones PhD, CMLI, Dip LA (Glos)

I am delighted to be asked by Terroir to contribute a guest blog – one that draws on my passion for both landscape and family history.

Over the years, as I collected my many family stories, I increasingly wanted to better understand the context in which they were made. My own personal journey into the past has also made me think a better understanding of the past can help us have a better understanding about some of the big issues we face today. Inequalities in access to land and nature is one of those hot topics that has been very much in the spotlight as a result of COVID lockdowns. To explore this issue further, I have chosen to talk about the story of land and landscape of the Welsh borders, and how, as ownership changed overtime, so did the fortunes of ordinary people depended on the land for their livelihoods.

Through dedicated genealogical sleuthing I have confidently traced my ancestral line in Shropshire through nine generations, and also found that my family name goes back to the beginning of the local parish records in the 16th century.

My forebears lived in, and around, Farlow, a small hamlet on the north-side of Titterstone Clee, whose name originates from the Saxon word for “ferny bank”. Farlow sits within a beautiful mixed landscape made up of upland pasture and lowland fields, which are peppered with farms, cottages and small holdings that originate from between the 16th to 19th centuries.

Where the slopes get steeper pasture turns into woodland, whilst lower down, near the old water courses, there is arable land and hay meadows.

It sounds idyllic, but the backstory of the Clee Hills is one of contested land ownership, privatisation and the erosion of common ownership. This is Border Country in every sense of the word. For those who were poor and living on the margin, the loss of their rights to access common land had a big, and irreversible, impact on their ability to make a living and put food on the table.

As my research became more extensive and involved frequent visits and walks in this beautiful countryside, I began to feel deeply connected to the Clee Hills and surrounding areas. Terroir explains why. Although Terrroir’s own origins stem from the word terra, the Latin for land, it doesn’t just mean the physical site or the visual landscape, but all the nuances that go with it. In South Shropshire I was discovering a terroir that wakens all your senses, especially a sense of being and a sense of place. Through the lens of family history, I had found a landscape narrative comprised of many rich layers, laid down in a line that stretched back to ancient times. To understand why this landscape is contested, I needed to look beyond the family story itself.

The first humans to arrive in Border country were ice age refugees, who had hidden in the caves of the Pyrenees. As it got warmer, the animals they hunted migrated north and, in pursuit, so did their hunters - now nomads in transit. Encountering the Great Wild Wood that cloaked much of Britain, they gradually carved out regular hunting and trading routes. Farlow sits on one of these ancient roots, known as the Clun Clee Ridgeway, that eventually terminates on the banks of the River Severn and the wider world.

After these nomads, came the first settlers and the first significant human land grab. These Celtic, Iron Age people, built a swathe of hilltop forts across the upland of South Shropshire, including several in the Clee Hills, of which one is Nordy Bank sitting at a natural vantage point and still intact. One of the imprints on the landscape that has lasted through time. It is a large, circular, enclosed area with stunning views, and thousands of years after it was built, was repurposed as a location for the open air gatherings of primitive Methodists. These were often long, all-day camp meetings of public praying and preaching, activities which my Wesleyan great, great aunts and uncles probably participated in with fervour.

From the Iron Age onwards, invasion after invasion continued to impact on the land. 55BC marked the arrival of the Roman’s in Britain, and though slow to conquer the Welsh Borders, a century later they were well established. Despite the aggressive land take, there were certain natural resources that the Romans believed couldn’t be privatised: air, sea, rivers, roads, parks, wasteland, cattle pastures, woodland and wild animals. Despite showing some respect for aspects for the natural world the Roman Empire proved to be unsustainable and eventually crumbled, as well all know.

The way of life of the newcomers, the Anglo-Saxons was very different, including how they farmed. My history lessons as a child told me that Anglo-Saxon settlement was more organic and less impactful than that of the Roman Empire. Although we now know that the transition from a nomadic to a settled way of life was one of the biggest historical milestones in climate change caused by the human race, there are lessons to be learnt from the Anglo Saxon approach. Their farming was a collective endeavour, which was localised, rather than centralised. Boundaries constructed were for protecting animals, not restricting the movement of people.

It was the Norman invasion of 1066 that marked one of the most dramatic changes on the relationship between people and the land in our country. William the Conqueror was adamant that all land, including all natural resources, belonged to the Crown. Much of South Shropshire became designated as Royal Forest, which overtime transitioned into Deer Parks with ditches, pales and stone walls to keep the landless out.

As a result the landless in South Shropshire were pushed into the marginal upland areas of the Clee Hills. On the southerly slopes of Brown Clee, at Heath, there is a small Norman Church, surrounded by lumps and bumps of a deserted village (one of many such villages). This is where the indigenous people migrated to, in order to survive.

As the climate deteriorated in late Medieval times, however, these higher marginal areas were abandoned, or turned to pasture – a process accelerated by the Black Death and resultant dramatic reduction in the overall population.

For many, the transition to pastoral farming did not result in better living and working conditions. During my research I found an academic paper studying the records made in 1524 about the people in Farlow and Stottesdon, and whether they made enough money to pay a lay subsidy to the King. Only a handful in Farlow, were able to do so: “nearly all the people of the area were in a state of wretched poverty, and the rest very close to that state”.

The roots of inequality in access to the land and to natural resources were now firmly established.

Part 2 - Enclosure next week

Imberbus

Way back in the 70s, I can recall a geography field course in Dorset. Our lecturer stood on the edge of a muddy track (it was probably in the Lulworth Ranges), reading out excerpts from Thomas Hardy. Behind him, on the MOD equivalent of a field course, rumbled assorted tanks. None of us was listening to Hardy; all of us were glued to the tank manoeuvres and the sheer incongruity of the situation. I have harboured an ambivalence to both Hardy and the MOD ever since.

Around that time there was a tendency to diss the MOD for negative impacts on its huge estate, particularly with regard to access, nature conservation and heritage. I was not overly surprised, therefore, to find that a committee had been set up in 1971, chaired by Lord Nugent of Guildford, ’to carry out a review of land in the United Kingdom held by the Armed Forces for training areas, airfields and ranges wherever situation [sic], and land used for any purpose in national parks and areas of outstanding beauty and along the coastline, except for dockyards and port installations’. https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1975/jan/17/defence-lands-and-national-parks

The Nugent Report was published in 1973, and is credited with a recommendation to appoint a MOD conservation officer. I suspect they also appointed a conservation savvy PR officer as, from memory, it was soon after, that we became increasingly aware of the extraordinary biodiversity which the MOD’s restricted access requirements was harbouring - although it was not until 2017 that the BBC’s Springwatch gave it the final seal of public awareness and approval by filming at Porton Down! https://www.gov.uk/guidance/defence-infrastructure-organisation-estate-and-sustainable-development#history

I was pondering this history while travelling on bus route 23A. The 23A used to connect various parts of east London with various parts of central London, but now has a much reduced timetable. Currently operated by the Bath Bus Company, the 23A runs a very frequent service but only on one day of the year. Welcome to the IMBERBUS.

This extraordinary day out is a bizarre partnership between transport fanatics and the MOD, who own the deserted village of Imber, in Wiltshire. According to the excellent Imberbus website – do take a look, particularly if you like history and/or buses (https://imberbus.org/introduction/) – the idea was concocted ‘On a cold winter’s evening back in 2009, over a few pints in a Bath pub, [when] four transport professionals discussed where the most unlikely place would be to run a bus service. The answer was a place that the public were not normally allowed access to and so the idea of running a bus service to the village of Imber on Salisbury Plain was born’.

Imber was once an isolated, rural village on Salisbury Plain, dependent on agriculture and supporting trades. Recorded in Domesday Book, by the latter part of the 19th century (see extract from 1899 Ordnance Survey below) it included various farms, a windmill, a school, an inn, a smithy, a Manor House (Imber Court), the parish church of St Giles with substantial vicarage, a Baptist Church and a shop. The ordnance survey map of 1922 records remarkably little change over the previous decades apart from, sadly, the inevitable addition of a war memorial, plus a wind pump and allotments. A rich store of old Imber photographs can be found at http://www.imbervillage.co.uk/imber-then.html

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland' https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

Significant changes were afoot, however. The War Office had been buying land to the east of Imber, for military training manoeuvres, since the late 19th century and physical damage to the village was recorded as a result of expanding activity prior to the First World War. By the late 1920s, the War Office was purchasing a number of farms around Imber, and bought most of the village, finding ready sellers at a time of agricultural depression.

The shadow of WWII caused another significant hike in training activity in the area, with a similar increase in damage to the village. On the 1st November, 1943, at a crucial point in the war itself, Imber’s landlords held a meeting in the village schoolroom and gave the villagers 47 days’ notice to quit, prior to using the village itself to train troops for street fighting. An interesting exhibition in the Church records that villagers assumed, or were told, that they would be allowed to return after hostilities ended, but no written records of such a promise could be found.

Today, Imber is a very different place. The church remains as a haven for wet visitors on open days and opens every year to celebrate St Giles’ day. Some other original buildings still remain and many others have been added to provide training facilities for warfare in built environments. The Baptist church was demolished in the late 1970s, but the grave yard with its yew trees remains.

Other original buidings are identifiable by their brick construction. The pub, below left, and the blocks known as the ‘Council Houses’, below right, are obvious, if now very sad, examples.

The original Manor House, Imber Court, still retains some of its grandeur, despite a few interesting additions (below right) but must look very different on military training days. We felt that the list of instructions had been followed meticulously.

Other former village buildings now mingle with the more recent MOD structures (below).

The village-scape has changed drastically too. The annual bus invasion is a delight but other signs are a constant reminder of the new Imber ‘inhabitants’.

And the village setting must also be very different. Gone are the open views, the occasional orchards, and the village gardens. Some grassland (one could hardly call it pasture or meadow) and hederows remain, but trees and shrubs have taken root in other areas and the village stream, known as the Imber Dock, is invisible, in summer at any rate.

It could be said that the MOD has destroyed one Salisbury Plain heritage and replaced it with another. Bus enthusiasts flock to Warminster to travel on the buses of their youth or, to a lesser extent, their parents’ youth. Many also come ‘for the ride’ and to take advantage of one of the few days per year when Imber village is open. It is also a rare occasion to take a trip across areas of the Plain usually closed to civilian traffic, and to partake of the glorious tea-and-cake-fest provided by the villages such as Market Lavington and Chitterne which lie beyond the Military ‘Danger Area’. So, perhaps one could construe this to be a very, very modest nod to providing some public access and, if not Salisbury Plain heritage conservation, at least military heritage interest and interpretation.