Downing or Drowning?

As political open spaces go, the garden behind 10 Downing Street must currently one of the most infamous. Access is extremely limited, of course, but the number of images on the internet does make a digital visit remarkably easy.

Gardens are powerful allegories and have always played a role in politics and the search for influence and control. What does this one in London SW1A tell us?

Originally, the garden had power stamped all over it. But prior to becoming the haunt of our political leaders, Sir Anthony Seldon’s history of Downing Street suggests a more modest inauguration. (https://www.gov.uk/government/history/10-downing-street). Apparently the Romans created their Londinium settlement on Thorney Island, a marshy piece of land in an area now called Westminster. No one made much of a go of the new community and Seldon suggests it was ‘prone to plague and its inhabitants were very poor’.

But lo, a series of kings arrived (Canute, Edward the Confessor and William I), and a great abbey was built. Government and the Church had arrived, and this section of Thames-side was now ‘on the map’.

Seldon also reports that the first building known to be on the Downing Street site was the medieval Axe Brewery. What glorious irony.

Then Henry VIII got involved and, via various political manoeuvrings, created the spectacular Whitehall Palace immediately adjacent to what is now Downing Street. Of course Henry needed a place to hunt and the area which later became St James’ Park, was laid out and enclosed.

From Van der Wyngarde’s View of London, 16th Century, British Library

Remnant walls have been discovered embedded in the dining room of No 10 and in the garden. (https://londongardenstrust.org/conservation/inventory/site-record/?ID=WST027a). With this shift of royal influence to Whitehall, domestic residences were soon being constructed around the Park and the Palace, for those wishing to live close to the power source.

In 1682, one George Downing obtained the lease and engaged Christopher Wren to build a cul-de-sac of terrace houses. Seldon comments, ‘It is unfortunate that he [Downing] was such an unpleasant man. Able as a diplomat and a government administrator, he was miserly and at times brutal.’ Seldon continues, ‘In order to maximise profit, the houses were cheaply built, with poor foundations for the boggy ground. Instead of neat brick façades, they had mortar lines drawn on to give the appearance of evenly spaced bricks. In the 20th Century, Prime Minister Winston Churchill wrote that Number 10 was: “Shaky and lightly built by the profiteering contractor whose name they bear”’. You just couldn’t make it up.

And here comes the exciting bit. Thanks to the London Gardens Trust, we can report a first mention of a Downing Street garden: ‘a piece of garden ground scituate in his Majestys park of St. James's, & belonging & adjoining to the house now inhabited by the Right Honourable the Chancellour of his Majestys Exchequer’. https://londongardenstrust.org/inventory/picture.php?id=WST027a&type=sitepics&no=1 Even more exciting, there is a picture, painted by one George Lambert at around the time of Walpole’s residency.

© Museum of London

As you can see, the image depicts the formal, rectilinear, controlled expanse of a fashionable, early 18th century garden. Two be-wigged gentlemen stand amongst straight lines – railings, paths, steps, lawns, trees – all backed by a substantial brick wall which clearly separates politics from St James’s Park. The only light relief as a classical looking statue, set into the wall, and a small black dog. This is a garden in corsets; the rolling English Landscape tradition has yet to happen and 20th century domestic gardens are not even a twinkle in anybody’s eye.

From then on, the houses on Downing Street were constantly remodelled, joined together, improved and extended, a process which continues today.

George II tried to give the house to First Lord of the Treasury Sir Robert Walpole. Sir Robert turned him down but suggested it become an official residency and actually moved in, in 1735.

Extract from ‘A New Pocket Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster 1797’ British Library

But what about the gardens? Looking at the Google image below, there have been radical changes. The Downing Street grounds have been cut off from St James’s Park and have, to some extent, embraced informality. The whole area behind house numbers 9 - 12 Downing Street has been combined into a single unit of about a quarter of a hectare. Earl Mountbatten has his own space, overlooking the Park.

Google Imagery © 2022

The ‘front garden’ is visible – just - to all and sundry, and goes for the formal, short grass, bedding plants and hanging baskets combination. Perfect for that sweeping shot from television cameras. No chance of Terroir getting in to get some more attractive shots.

This back garden is no longer a statement of power and influence in its own right but a utility which has been forced to cater for a multitude of functions. These functions include the garden as play area for young families (Blairs, Browns, Camerons, Johnsons), as a place to grow vegetables (Michelle Obama’s influence on Sarah Brown), a setting for important visitors (including the Barak Obama/Cameron barbeque for military personnel), as stage for state visits and formal events, asan occasional venue for London Square Open Gardens Weekend, as a resource for the increasing numbers who work there and, now, as a Covid facility for fresh air, meetings, explanations, apologies, thanks and other forms of showing appreciation to the in-house team.

As a result, it is appears that the garden has a bit of everything except a cohesive design. From recent internet images, we have spotted a mix of small trees, large shrubs, whole shrubberies, herbaceous planting, perennial planting, bedding plants, hedges, bulbs in beds, bulbs in grass, raised beds, urns, yards of Wisteria, mounds of roses, lots of close mown lawns, assorted path surfaces and two ghastly municipal style lighting bollards. Oh and a huge terrace for, err, sitting out on.

It also appears that the garden sports some massive plane trees but this is actually a ‘borrowed landscape’ and these classic Londoners lean in and peer down from outside the garden walls.

View from Horse Guards Road of the ‘borrowed plane trees’ and the back of 12 Downing Street Google Imagery © 2022

It’s all maintained by the Royal Parks. Do look at this YouTube video (https://youtu.be/RMwL3GYtqjo) to get a real taste of what it takes to keep the space immaculate for any ocasion, with or without warning.

What does this horticultural jumble tell us? I would suggest:

A lack of respect for open spaces; you can take a virtual tour of the inside of 10 Downing Street (https://artsandculture.google.com/u/0/story/twXxuEIPr4FZJA) but not of the garden.

A failure to demonstrate good design.

An own goal for lack of sustainable management and biodiversity.

A lost opportunity for British horticulture.

A return to a good old fashioned head gardener.

Are we too harsh?

Perce-Neige

Snowdrops: the first flowering bulb of spring. What’s not to like?

When the Head Gardener of Gatton Park in Surrey takes you on a tour of the garden’s snowdrops, in advance of their first ‘open day’ of the year, snowdrops deliver at their delicate best. Set in a Capability Brown landscape perched on the North Downs, and accompanied by stunning views and the scents of Daphne and Sarcocca (Sweet Box), it’s a pretty sensual experience.

But is this delicate, early spring flower (the snowdrop, not the Sarcocca which is anything but delicate), able to overcome the clichés and past associations which follow it around?

Snowdrops in poetry are definitely seen as symbols of hope, purity and solace. I do have problems with the Romantic poets, however. Try Wordsworth (1770 to 1850):

From To a Snowdrop

“Chaste Snowdrop, venturous harbinger of Spring,

And pensive monitor of fleeting years!”

This ‘chaste’ thing is quite something for a flower which, in a stiff breeze, is quite happy to flaunt its frilly underskirts. What is the first thing we do when up close and personal with a snowdrop? Turn a flower upside down to admire the delicate floral layers within.

Tennyson (1809 -1892) was also a fan of the snowdrop purity angle. Think of this famous two liner from

The Snowdrop

“Many, many welcomes,

February fair-maid!”

or this extract from

The Progress of Spring

“Wavers on her thin stem the snowdrop cold

That trembles not to kisses of the bee”

No way was Tennyson going to identify the snowdrop with a knight in shining armour or a king’s courtesan.

Christina Rossetti (1830-1894) (technically brilliant, but in my view very capable of schmaltzy platitudes) actually fares better:

Another Spring (first verse)

“If I might see another Spring

I’d not plant summer flowers and wait:

I’d have my crocuses at once,

My leafless pink mezereons,

My chill-veined snowdrops, choicer yet

My white or azure violet,

Leaf-nested primrose; anything

To blow at once, not late.”

Or

The First Spring Day (again Verse 1)

“I wonder if the sap is stirring yet,

If wintry birds are dreaming of a mate,

If frozen snowdrops feel as yet the sun

And crocus fires are kindling one by one”

At Gatton Park it’s the fiery aconites which this year out-compete the crocuses, and we’ve already commented on the sweet smelling Daphnes even if they are D. bholua rather D. mezerium/mezereons.

The Hellebores (below left and centre) and a witch hazel (below right) also contribute to the spring show.

Despite the best efforts of the Romantics, or possibly because of them, the Victorian snowdrop began to develop a darker personality. Some suggest that, as snowdrops became popular to plant in graveyards, the flowers became associated with bad luck and a harbinger of death rather than spring. (https://escapetobritain.com/snowdrop-history-galanthus-nivalis/)

The 20th century snowdrop, however, seems to have survived this bad press and became a very popular addition to gardens and parks as well as poetry. Enthusiastic amateur and professional horticulturalists have developed many new varieties with subtle differences in the size of flower and the pattern of green markings on and within the blooms. Gatton Park features Galanthus elwesii and G. ‘Flore Pleno’ as well as G nivalis.

Perhaps it is not surprising, therefore, that 20th century Snowdrop imagery seems to be much more robust, and references to purity have tended to shift to more sombre themes.

East Coker, No. 2 of T S Eliot’s Four Quartets (surely tautology - how likely is it that there would be three or five quartets?) is, inevitably, rather disturbing but, in my view, very exciting and, in this extract, very pithy about hollyhocks:

“What is the late November doing

With the disturbance of the spring

And creatures of the summer heat,

And snowdrops writhing under feet

And hollyhocks that aim too high”

(Please don’t tread on the flowers).

My favourite Snowdrop discovery, however, is Louise Gluck’s Snowdrops - perfect for a 21st century in pandemic.

“Do you know what I was, how I lived? You know

what despair is; then

winter should have meaning for you.

I did not expect to survive,

earth suppressing me.

I didn't expect

to waken again, to feel

in damp earth my body

able to respond again, remembering

after so long how to open again

in the cold light

of earliest spring”

Many gardens open to the public in February to display their collections. Terroir will be going back to Gatton Park on Sunday 6th February. This is not a woodland garden display, but rather a spread of snowdrops naturalising through the Edwardian flower and shrub beds, under massive veteran trees, or spilling down grassy slopes. The ’drops trim the Brown landscape with green and white lace, showing that once more, snowdrops are able to remember,

“how to open again in the cold light of earliest spring“.

See you there.

Heaven and Hell

Thanks to Covid rules, Terroir spent a surprising amount of lockdown time in the village of Chaldon, perched high on the North Downs in north east Surrey. Whilst our Bubble visited in the residential care home (once the Rectory, below right), Terroir paced the lanes and footpaths, tarried in the Church of St Peter and St Paul and puzzled over historical enigmas.

There is enough history in this tiny village to fill a book. In fact, that book is no. 7 in the local Bourne Society’s series of Village Histories http://bournesoc.org.uk/.

Both the Bourne Society and its publications can be highly recommended. Village Histories No 7 (‘Chaldon’) fills nearly 200 pages with the results of extensive research and fascinating images of old maps, documents and photographs of village life and historic buildings.

But, as with all good books, it leaves some questions unanswered. Two questions have been niggling Terroir: who created the earliest known English wall painting, on an inside wall of the Parish Church and, what is behind the curious statistics relating to those who lost their lives in two world wars?

Before we tackle these issues, however, we can provide you with a taste of Chaldon’s back story. The village is only 17 miles from London’s Hyde Park Corner, and extremely close to Surrey’s only major east/west route (Chaldon is a mile from the so called ‘Pilgrims’ Way’ to Canterbury, and less than 5 miles from what is now the A25). Yet the village remained an agricultural hamlet with few amenities until after World War I. Despite archaeological finds representing 5 prehistoric periods, despite documentary references which may date back to AD 727, despite a mention in the Domesday Book, despite underground ‘quarries’, despite the arrival of the railway in nearby Caterham in 1856, Chaldon remained, for centuries, a largely agricultural community. In 1801 the population was around 100, rose to 280 in 1891 and then dropped to only 266 in 1901.

Yet, sometime prior to 1200, someone (or perhaps some people?) painted the most extraordinary picture on the west wall of the Church, a building which nestles close to one of Surrey’s many north/south trackways, at the northern tip of the modern village. At some point the painting was whitewashed over, but was rediscovered in 1870 and has subsequently been cleaned, restored and conserved on more than one occasion.

To quote Village Histories No. 7, the picture “is without equal in any other part of Europe. It is thought to have been painted by a travelling artist-monk with an extensive knowledge of Greek ecclesiastical art. The picture depicts the ’Ladder of Salvation of the Human Soul’ together with ‘Purgatory and Hell’”. It is, to the modern eye, exceptional, astonishing, visceral, blood curdling and stomach turning, and, in the phraseology beloved of Michelin guides, well worth the journey.

I doubt that Terroir’s desire to know more about the artist will ever be satisfied.

Terroir’s second niggling question also arose from a visit to the Church and has been exercising the Terroir mind for some time. We have asked around for views but, unusually, have decided to blog about this issue before reaching a conclusion, in case others can offer any thought on what follows.

A stone memorial on the south wall of Chaldon church commemorates those who died in WWI. Seven names are recorded including two of the then curate’s sons who died within three days of each other at the Dardanelles in 1915. A seond memorial tablet (left) commemorates the brothers’ military service in the Wiltshire Regiment.

The Chaldon Village Council website (https://chaldonvillagecouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Chaldon-Matters-Winter.pdf) suggests that the roll of honour should actually include 10 names, so there is yet another mystery for which Terroir would welcome an explanation.

A third church memorial, in the form of a window, commemorates those lost in World War II, with 16 names including that of Lance Corporal John Harman VC, nephew of the William Harman who was commemorated on the WW1 Memorial.

There was something unusual about this window and it took a moment to realise that this was the first war memorial Terroir has seen where the list of names for WWII is longer than that for WWI.

The most popular theory to account for this apparent anomally, and indeed one which occurred to ourselves, is an increase in the population of Chaldon due to the expansion of the village during the inter-war years. This was a time when speculative builders constructed housing estates throughout Brtiain, and this uncontrolled building boom did much to prompt the post WWII planning regulations (we touched on this in last year’s Blog 21 - ‘Privet Land’).

On reflection, however, Terroir is still not convinced that this is the sole cause of Chaldon’s greater number of WWII deaths. Surely the Chaldon 1920s/30s expansion occurred in all the local villages? We cannot think of a village without some evidence of the classic ‘Tudorbethan’ design of the period (below left) but somewhat pared down for the construction of council houses (below right).

We also visited a number of local war memorials (online and in person) and nearly all demonstrate the usual pattern of, sadly, many more names carved on the original WWI memorials, than were later added to commemorate losses caused by WWII.

A summary of our ‘research’ to date is presented below. This is where you all have a good laugh at our cod stats. Yes we know we don’t have nearly enough data to make any of this significant, and no we haven’t listed our sources, or checked how comparable our data is. Talk about off the cuff. But, even at this stage, the investigation hints that it is very unusual to have more people die in WWII than WWI. It also hints that it is hamlets and villages with few inhabitants, which may not follow the typical pattern. At any rate, we are willing to stick our necks out far enough to say that we don’t think it is necessarily to do with inter-war village expansion, which was not exclusive to Chaldon.

We will continue collecting data but for now, we beg for comments from those who know far more than we do, about Surrey villages and their heroic contribution to two world wars.

Common History

OK, so let’s tackle the elephant on the heath before we get stuck into this week’s blog.

No doubt all Terroir readers know this, but just to be certain, common land is NOT owned by ‘everybody’ or the ‘community’ or the ‘commoners’. It will be owned by someone (eg the Lord of the Manor) or, more often these days, by some body (such as a local authority or the National Trust), who are responsible for managing what happens to it.

By a happy coincidence, Terroir recently visited Limpsfield Commons and also obtained a copy of Shirley Corke’s posthumously published book of the same name.

Shirley Corke’s detailed and quite extraordinary history of the Commons is the result of a historical landscape survey, commissioned by the National Trust in the 1990s. If you want to experience the life and landscape of lowland common land through time, want an exemplar in how to research and interpret a landscape, or live locally and want to delve into your local history, then this is the book for you (and no, we’re not on commission!) https://limpsfieldsurrey.com/2021/12/07/limpsfield-commons-new-book-on-our-beautiful-common-now-available-for-purchase/

Limpsfield parish is in the far east of Surrey, right on the Kent border (and is none the worse for that). It is geologically diverse, stretching down the scarp slope of the North Downs (lovely views), over the intervening ribbon of Gault clay (spring line villages), back up onto the Greensand Ridge (more in a bit) and then down again onto the clay lands of the Low Weald. Limpsfield Common and Limpsfield Chart are, like so many commons in Surrey, located on the Greensand.

Here’s an image of what it looked like around 1893.

Extract from Ordnance Survey, One-inch to the mile, Revised New Series Revised: 1893 Published: 1895. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland' https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

The concept of a Surrey Heath is often perceived to be a heathery expanse of acid sandy common land, once grazed and now rapidly disappearing under a sturdy layer of post war, upstart woodland or housing, or a thinner veneer of military training land or golf course. Limpsfield’s commons do illustrate much of this but Corke’s history may imply a more complex history than many of us realised.

What has Limpsfield got today? Predictable, perhaps, the short answer is trees – lots and lots of them - and a golf course. Both Limpsfield Common and Limpsfield Chart are registered Commons, are open access land and are owned by the National Trust. The High Chart is none of these and is privately owned but at times it’s hard to tell the difference. All three areas are heavily used by walkers, strollers, dog exercisers - in other words anybody who fancies a breath of fresh air. There are public footpaths everywhere, and a plethora of forest rides and tracks on the High Chart which obviously get well used too. There is the Greensand Way, the Vanguard Way and even the Romans had a ‘way’ here in the shape of what is described as a minor Roman Road. Is this the Roman equivalent of a ‘B road’, or our modern historians’ denigration of what the Romans did for us?

Below - Limpsfield Common: lots of deciduous woodland, tracks and paths, car parks and welcoming signs and golfers; there is even some remnant heather.

Below - Limpsfield Chart and High Chart: Limpsfield Chart is not dissimilar to Limpsfield Common but as you move into the High Chart the scale changes and so does the woodland. Here is Ancient Replanted Woodland, with stands of ‘exotic’ conifers amongst the native and deciduous species. There is evidence of ‘commercial’ forestry and Forestry Commission grant schemes. But the easy access and woodland mix still makes for a grand afternoon out.

Back in the 11th Century, Limpsfield Estate belonged to one Harold, he who met his end when opposing William of Normandy at the Battle of Hastings. Subsequently, William I (aka William the Conqueror) gave the estate to the monks of Battle Abbey. By the 14th century, this Abbey outlier seemed to be fairly prosperous, and a document of 1312 makes mention of dovecots, water mills and fisheries. Corke notes that the list of woodlands is long. Three of these woods (Chert, Echenwode and Stafherstwode) “are common to all tenants of the manor both free and unfree throughout the whole year for their animals”. There is also mention of other woods which could offer rights of pasture, and seasonal ‘pannage’ ie for pigs to feast on fallen acorns at the appropriate time. In addition, documents indicate the presence of arable land, meadow and pasture, but Corke points out that there is no mention of open ground or of heath, gorse or furze.

The 15th century has been interpreted as one of neglect and decay and, by the Dissolution of the Monasteries (including Battle Abbey, of course), there Corke now finds reference to extensive areas of heath and furze. The customs which protected (or limited!) tenants’ rights, and the value of the commons (probably supporting a mixed landscape of woodland, underwood, and wood pasture, as well as arable and open pasture) were clearly being flouted; change would have been inevitable. The reduction of the population during the Black Death, suggests Corke, may also have resulted in the conversion of arable to heathland.

It is tempting to talk about many other fascinating aspects of Commons – reductions in area due to encroachment, of ‘digging’ (for clay or other useful products), of changes in agricultural and silvicultural practice, of social, economic and legal changes, but I will not steal Shirely Corke’s thunder and leave her to entertain and inform you on these topics.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, under the ownership and stewardship of the Leveson Gower family, the somewhat fragmented estate was being partially reassembled, but despite many other changes, the commons are still windswept open spaces, although the march of recolonising deciduous woodland can just be detected by the early 20th century.

In the 1920s, however, the Leveson Gowers bought out a number of commoners’ rights, and made the commons available for public ‘air and exercise’, to be managed by a committee of local people. In 1972, Richard Leveson Gower gave the Commons to the National Trust (https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/limpsfield-common). The High Chart – always wooded - remained as part of the family’s nearby Titsey Estate. By the 1960s, the return to woodland is pretty much complete.

All map images reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland' https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

To summarise a book of some hundred pages, and with extensive illustrations, in three paragraphs is ridiculous. Buy it, read it, and lose yourself in the world of an ancient estate. And don’t worry about the technical stuff (avowsons, copyhold, dottards, firbote and Frankpledge). There is an excellent glossary at the end.

Mining the Past

January is supposed to be the most difficult month of the year. Limited daylight, limited sunshine, limited garden and allotment time, inhospitable weather. Friends with Covid, friends with ‘the’ cold, the perceived need to detox after Christmas. The BBC reminded me recently that there won’t be another bank holiday for over three months, although Terroir sees this as a mixed blessing, as extra days off just seem to breed bad temper over the health, social, moral and legal implications of a day out.

Today, I am admiring the sunshine picking out the frost on neighbours’ roofs and the skeletal details of a sycamore tree creating its own sculpture garden and converting its backdrop (uninspiring urban architecture) into works of art. Get your kicks where you can. But yesterday, I spent the day in a sunny Northumberland, courtesy of the Terroir photo library and last summer’s lighter lockdown restrictions. Welcome, I hope, to a little uplift, to a virtual day out.

Hadrian’s wall (above) is a magnificent symbol of Northumberland (and Cumbria of course) and, as we were staying in Greenhead, which is pretty much at the midpoint of the wall, we spent our first few days wallowing in, on and around Roman remains. Here are a few classic tourist pictures.

As time progressed and as we read and visited more widely, mining became a recurrent theme, a sort of ground bass, if you will pardon the pun, to our visit. You will probably know all this, but Terroir was surprised at the variety and longevity of local mining and quarrying. Key commodities were limestone, sandstone, iron, lead, silver, zinc, lime, clay and, of course, coal. Mining has been going on for a long time in this area. A useful Historic England publication (https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/iha-preindustrial-mines-quarries/heag223-pre-industrial-mines-and-quarries/) suggests that Northumbrian communities as far back as the Iron Age had been quarrying stone for round house construction and for quernstones with which to grind flour.

Of course stone quarrying must have expanded significantly with the arrival of the Romans but production must have gone into overdrive after Emperor Hadrian landed in AD122 and ordered construction of a wall from Wallsend on the Tyne in the east to Bowness on Solway in the west.

Below: views of the dolerite Whin Sill cliff (which provided a natural route for much of the wall) and adjacent stone quarries.

Stone quarrying continued after the Romans left, with much plundering of the pre-cut, Roman wall-stone as well as production of newly quarried stone.

Below - some post Roman uses for the local building material

From left to right: Thirlwall Castle 12th century with subsequent alterations, listed Grade I/Scheduled Monument. Featherstone Castle 13th century with subsequent additions and alterations, listed Grade I. Greenhead Parish Church 19th Century, listed Grade II. Greenhead Methodist Church (now youth hostel), 19th century.

Quarrying contiuned into modern times with, unsurprisingly a rather mixed impact on the environment.

Below left - an artist’s impression of Cawfields Milecastle. Below right - an artist’s impression of Cawfields Quarry, located just under the Whin SIll, and where later mining of the Sill’s hard dolomite (great for road surfacing) destroyed the Roman structures above.

But where did the iron, lead, silver, zinc, lime, clay and coal fit in? Two aspects got us interested in these commodities. One was a day spent exploring Haltwhistle and the other was the Newcastle/Carlisle railway line which passed within yards of our accommodation, although Greenhead Station itself had been subject to Dr Beeching’s cuts in the 1960s. We’ll use these two settlements as examples of how pervasive mining used to be.

The railway is a particularly early route which opened in phases between March 1835 and July 1836. Such was the value of local products, and the need to get them to ports and markets, that transport improvements around Carlisle and Newcastle were being planned from the second half of the 18th century. A Carlisle/Newcastle canal was seriously considered. But once railways became a realistic option, and despite significant opposition to this noisy, smoky new-fangled transport, there was really no contest. Railway infrastructure was a fraction of the cost of canal building.

Coal had been mined at Haltwhistle since the 1600s and around Greenhead since at least the 1700s. But, thanks to the Haltwhistle Burn, the town also had significant woollen and corn mills, lime kilns and brickworks. The coming of the railway revolutionised all these local activities. But Haltwhistle was also located relatively close to the north Pennine lead ore area with production centred on Alston and Nenthead. Exporting both lead and the associated silver by road was slow and costly but the promise of a rail head at Haltwhistle changed the eonomics - and the industry - dramatically. Apparently lead was being stockpiled at Haltwhistle before the railway even opened.

Below, left to right: history of Haltwhistle and historic view of the Station; Haltwhistle Station today; ‘The rise of industry’ information plaque.

In today’s post industrial era, things are much quieter. Despite the loss of Greenhead’s station, the railway still functions as a strategic, coast to coast link, carrying mainly passengers and the occasional nuclear flask en route to Sellafield's reprocessing plant.

Above: the flask train passes through another classic Carlisle and Newcastle Railway station; this one is Wylam, to the west of Newcastle.

But the railway faces competition now for the honour of transporting walkers and visitors to the beauties of the wall. It may only run in summer but route AD 122 (geddit?) is an excellent way of travelling between Hexham and Haltwhistle via Greenhead and the must-see highlights of Hadrian’s massive construction project.

The Boxing Day Walk

The Boxing Day Walk: a magical British tradition when happy families scuff their Wellington boots through drifts of frosty, fallen leaves, enjoy the simple pleasures of walking through our wonderful, picturesque countryside before returning, invigorated and at peace, to a classic yet multi-cultural repast of cold turkey, cold roast potatoes and cranberry sauce (all of American origins) and chutneys (from our Indian empire). For once, let’s celebrate, and not berate ourselves, for our traditions.

Alternatively…

For starters, the Terroir Boxing day walk was technically not on Boxing Day but on ‘Substitute Bank Holiday for Boxing Day’. But, despite the nomenclature and lack of frost, we did indulge in some rural magic.

This was a walk rich in history, in ancient woodland, traditional coppicing and Sites of Scientific Interest. Rich in ancient monuments, Roman roads, listed buildings, vernacular architecture, large houses and small cottages. Rich in former hop gardens, orchards, pack houses and parkland, old sand quarries and other allusions to the rural economy. There were old trees, young trees, deciduous trees, coniferous trees, parkland trees. There were Shetland ponies, horses, cattle, and, if you read last week’s blog, you will already be acquainted with the very large, black bull. There were also some very fine views. All this in a walk of less than 4 miles.

But of course, if you travel with Terroir, there are always issues.

One of the most spectacular vernacular buildings on our route was an 18th century water mill, located on a brook (obviously), in a shallow valley, with substantial mill ponds engineered to provide sufficient energy to drive the water wheel.

The mill was converted into a house sometime in the first half of the 20th century and listed grade II in 1958. It was on the market in 2015 (3 recep, 6 beds etc etc) for a guide price of £2.75m.

Terroir approached the mill with anticipation, expecting at least one attractive view of a fine building. Sadly, this classic mill of brick and weather board, and mansard roof, is now largely invisible, hidden as it is, behind high board fencing and hedging. The images above are about the best we could do. Those below show some of the boundary detailing.

Why would you buy an expensive house and then hide it from view? We all like our privacy, of course, but most of us live in villages, towns or cities, and have little scope for 360 degree seclusion. Granted this house and (large) garden are surrounded on all side by public rights of way. A modicum of discrete fencing and hedging would be expected. This mill conversion, however, squats behind high fences which almost entirely hide the plot from passing walkers.

Terroir sees a number of issues. Those with fine houses of architectural merit are often pleased to allow glimpses to others. This may, I suppose, stem from a desire to display their particularly fine accommodation, but I think this is over cynical and many want to allow others to share in the delight of a fine house, a vernacular working building nicely converted and/or a piece of history which makes the British countryside so attractive and interesting. This is our heritage too.

These structures are also an intrinsic part of our landscape: built of local materials (wood, clay bricks and tiles), positioned to exploit natural topography and renewable energy, created to process locally grown grain to supply a local-ish market. As such, a mill is a significant piece of its wider local context. The mill and its raison d’être is part of what makes this part of south east England characterful, distinctive and precious. But this one has been cut out of the view by its fences and can no longer make its contribution to our cultural landscape.

And that view comes with the house for free. Well, actually, probably not – it probably increases the house price significantly. So why block it out? We can’t see this listed building, but neither can those who live in it, see the wider view. And if they do go out to enjoy the wider landscape, they can’t appreciate their house; their heritage home is as much hidden to them as it is to us.

And of course, what we do see, residents and passers by alike, are those very overbearing fences and thuggish laurel hedges. Potentially see-through iron gates are blocked off, footpaths turned into high security alleyways and side entrances guarded by massive timber structures, so big and heavy that a crude postern gate has had to be added.

On a positive note, one of these paths has been designated as a permissive bridle way. The ironic consequence, however, is that anyone on horseback could probably see over the fence while riding by. Those of us on foot cannot. Where public rights of way do provide lovely views of the mill pond (part of an SSSI but classified as ‘Unfavourable/Declining’ when last surveyed), anxiety over the dam structure has led to a crude attempt to dissuade access (below right).

As a nation, we try to honour our natural and built environment. The mill is already valuable enough to encourage its conservation via the Listing system, but users of public footpaths can no longer see it. Such fencing may deter thieves, but there will always be unintended consequences and such screening provokes huge curiosity about what wonders may lie within. For the passing pedestrian, the temptation to climb on anything which will provide view over the barricades must be very tempting indeed!

2022 - A New Way?

Which route should we take in the coming year?

Ambition versus feasibility? Will you challenge or stick to the footpath?

Whichever you choose, good luck and best wishes for 2022.

It’s a Christmas Wrap

It was a very simple question: ‘please send a picture of your favourite wrapping paper’. Inevitably, the response was invigorating and varied in terms of both designs and commentary.

Original 1960’s wrapping paper ‘rescued from a junk shop on the banks of Cenarth Falls in West Wales’. ‘It is so nostalgic which is what Christmas is about for me … I was brought up with a make do and mend mindset … . Every year the paper was saved and recycled … and still is.’

Seasonal vegetation was a popular theme. All these are recyclable and the holly on the right is also made from recycled paper.

‘Not sure I have a favourite. Haven’t bought … paper for a couple of years as I bought a load … for about 10p a roll.’ ‘[I’m] using this one.’

The charity volunteer: each shoe box is covered with a different design of wrapping paper (and is filled with goodies for those who may not get anything else on Christmas day).

© A Lankester

A trio of more diverse habitats; the bird theme is very strong. The wrapping in the middle is not recyclable but at least it is on its second or third Christmas.

The creatives:

‘In an ideal world I would have decorated plain brown paper, but the world has not been ideal this year!’.

‘I always come back to using brown paper either with big name labels cut from the previous year’s Christmas cards or as here, decorated with paint brushes’.

The eco-warriors. And a number of you mentioned recyclable/plastic free tape.

Whatever your taste in parcel paper, Terroir hopes that you have someone to wrap for and someone who is wrapping for you.

With very best wishes for a relaxing, enjoyable and peaceful Christmas.

Briefly Bradford

When we announced we were going to Bristol, friends and neighbours were envious.

When we announced we were going to Dundee, people admired our sense of adventure and knew about the Tate Gallery.

When we said we were going to Bradford, everyone thought we’d lost the plot completely.

To be honest, we went to Bradford because Grand Central was offering cheap train tickets, but we also wanted to visit Saltaire, and had ‘things to do and places to go’ across Yorkshire from Leeds to Sheffield and a lot of points in between. The more people scoffed at our destination, however, the more determined we became to see something of Bradford itself. We can hardly be said to have made an exhaustive exploration of the city, but we did spend time walking the streets in day light, at dusk and after dark.

So this is a starter blog about Bradford. Were we mad or just ahead of the game?

We have to admit that at first glance, Bradford does not overwhelm. Our brief visit to Halifax, for example, immediately placed the mill town on the ‘need to spend longer here’ list. Bradford doesn’t do that but there is a lot to see. Bradford’s cityscape and architectural heritage comes in all shapes and sizes, from industrial heritage, once-proud commercial and trade edifices, Yorkshire corporate pride, theatres, schools and places of worship. It is also in all states of repair from actually under demolition, to derelict and unloved, used but shabby, in good nick, recently-renovated, or even brand new.

Two things became very clear, however. This is a city where migration has played a major part in its history and development. And this is a city where buildings created by one community have been frequently reconfigured to fulfil the needs of another.

But let’s start at the beginning. According to various sources (eg https://www.visitbradford.com/history-of-bradford.aspx and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bradford) Broad Ford, later Bradford, was first settled in Saxon times.

Bradford Cathedral (right): worship on this site may go back to Saxon times, although the current buiding dates from the 15th C onwards

Bradford had become a small town by the Middle ages and, over the next couple of hundred years, continued modest growth and started a bit of a speciality in wool trading. Spinning and weaving was a local cottage industry.

The 18th century saw the development of manufacturing using local natural resources such as iron, coal, limestone, and sandstone for construction. The wool industry mechanised, transport improved (water ways and turn pikes) and, hey presto, by 1850, Bradford had become the wool capital of the world. ‘Worsted’ was their speciality, considered stronger, finer, smoother, and harder than ‘woollen’ cloth.

Below: Bradford Wool Exchange - a classic Victorian homage to industry and entrepreneurial activity

Migration was part of this story. The first to arrive in any numbers were from Ireland. The Irish started to arrive from 1800 onwards but the biggest influx occurred in the 1830s and 40s. Discrimination was rife, as were terrible living conditions, illiteracy, and low wages, as the better paid jobs appear to have been reserved for the locals. By 1851, around 10% of Bradford’s population had been born in Ireland.

In 1829, the first textile trader arrived from what is now Germany. This was the start of a very different sort of community – many (although by no means all) were wealthy, successful and influential, adding synogogues to the protestant and catholic churches which were already diversifying Bradford’s religious architecture. By 1841, one in eight people had been born outside Yorkshire and 24 out of 52 ‘stuff merchants’ had German names.

The second half of the 19th Century must have seen a terrific building boom in Bradford. We found evidence of the many substantial Victorian structures which supported and celebrated Bradford’s industrial and trading status.

Below: the magnificent, Italianate City Hall

One particular area, however, provides a substantial architectural memorial to the influence of migration. German owned warehouses started to spring up in an area now known, unsurprisingly, as Little Germany, immediately to the north east of the town centre.

The images below, and the mural of Hockney at the start of this blog, illustrate just a small sample what we saw; some buildings are forlorn and decaying, others converted to appartments or modern commercial uses. All are, or were, ornate, massive and oozing confidence.

At the start of the Great War, some Germans left, some were interned, some served in the British forces and many of Bradford’s Jewish community are thought to have changed their names.

Post World War II saw the start of the next big flow of migrants, this time from India (which then included Pakistan and Bangladesh). During the late 1940s and early 1950s Muslim men came to work in Bradford, although the city’s first mosque didn’t open until 1959. By the ‘60s and ‘70s most Asian men had decided to stay and sent for their families to join them. There are anecdotal reports of whole villages reassembling themselves in Bradford. Some West Indian families also came. By 2011, Bradford`s population was 522,452, of which 26.83% were Asian and 24.7% muslims.

Places of worship seem to have inspired the most creative and flexible attitudes to buildings. Although new churches, mosques and synagogues have been built, many structures which started as a home for one faith have been reworked for the use of others.

Churches, for example, have changed denominations or been transformed into mosques or temples, while secular buildings such as hotels and cinemas have been – well, converted, if you will pardon the pun - for religious use.

Bradford was established as a City of Sanctuary in 2008, and continued to live up to that name in 2016 by taking a large proportion of the Syrian refugees given asylum in the UK as a result of the Syrian civil war.

I doubt that this level of diversity has ever been easy, but it does make Bradford interesting. Our short visit was very worthwhile and leaves us curious to return.

This is also a short blog, and apologies for failing to mention the Italians introducing ice cream, Russian Orthodox Jews, German pork butchers, Belgium refugees, Basque children fleeing the Spanish Civil War, the 1939 Kindertransport arrivals, Indian lascars (seaman), Vietnamese Boat People, the large Bradford Polish community and probably many others unknown to Terroir.

Many thanks to a fascinating Historic England Document, ‘Migratory History of Bradford, which supplied much of the detailed above information: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiLyMG4hOb0AhVQKewKHe8IAEcQFnoECAIQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fhistoricengland.org.uk%2Fcontent%2Fdocs%2Feducation%2Fexplorer%2Fbradford-timeline-doc%2F&usg=AOvVaw1dQD9Xmw9TJ-C8kQJg4mlg

Salt and Society

Google ‘Titus Salt’ (1803 - 1876) and you will come up with a range of key words and topics which may well chime with our conception of who Sir Titus was and what he sought to achieve.

‘Manufacturer, politician and philanthropist’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Titus_Salt)

‘Largest employer in Bradford’ but ‘Bradford gained the reputation of being the most polluted town in England’ (https://spartacus-educational.com/IRsalt.htm)

‘alpaca hair’, ‘produced a new class of goods’ and ‘Saltaire [became] … the most complete model manufacturing town in the world’ (https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1900/Salt,_Titus)

But read the histories more carefully and you will find that the story was, inevitably, far more complex than many of us might perceive. Did Salt make a lasting difference? Was he interested in philanthropy or was it a form of social engineering? And what is his legacy?

Most commentators appear to agree that Titus Salt, a man of relatively humble origins, was truly appalled by the conditions prevailing in Bradford in the first half of the 19th century.

After two years as a wool-stapler or wool trader in Wakefield, Salt moved, in 1822, to Bradford and eventually joined his father who had also set up as a wool-stapler. Salt junior seems to have introduced a Russian Donskoi wool, but found that the Bradford wool mills refused to handle this rough product, so he worked on creating specialist machinery which could handle the wool and set up a mill of his own.

By 1836 he had four mills and, after the purchase of a large supply of alpaca hair, no doubt going at a knock down price for the same reason as the tangled Donskoi wool, he introduced a new alpaca textile and became a very wealthy man.

Meanwhile the population of Bradford had expanded hugely (an eightfold increase over the first five decades of the century) and conditions for the mill workers are reported to have been dire. Over 200 factory chimneys belching smoke, sewage polluting drinking water, outbreaks of cholera and typhoid and appalling levels of infant mortality (see https://spartacus-educational.com/IRsalt.htm for a graphic account of the conditions). Salt discovered that the Rodda Smoke Burner significantly reduced stack emissions but failed to persuade fellow mill owners to install it as he had done in his own mills.

Construction of Salt’s new model factory commenced in 1851 and took two years to build. The site was three miles outside Bradford’s polluted city centre on the banks of the river Aire, the Leeds and Liverpool Canal and the Midland Railway. A very rural and yet very connected site.

Map image reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

The whole site was listed as UNESCO world heritage in 2021 (https://saltairevillage.info/). Salt’s Mill, as the Italianate mill building is now called (listed Grade II*) (above), was designed by Lockwood and Mawson as a ‘Palace of Industry’. It faced the railway and ‘was to be, externally, a symmetrical building, beautiful to look at, and, internally, complete with all the appliances that science and wealth could command’. Money was no object and indeed, it is reported that ‘Lockwood and Mawson’s first design for the mill, costed at £100,000, was rejected by Salt as being ‘not half large enough’.’ (https://saltairevillage.info/Saltaire_WHS_Salts_Mill.html).

Today it functions as a Hockney gallery and retail space. When Terroir visited, the ground floor was full of colour, vibrancy, excitement - and lots of upmarket retail opportunities. Upstairs, the queue for the ‘Diner’ was far from exciting, so we went elsewhere.

Once the mill was up and running, a dining room was constructed and then 850 houses - hammer dressed stone with Welsh slate roofs - so that Salt’s 3,500 workers no longer had to commute by special train from Bradford. Each house had its own outside toilet, gas for lighting and heating, and a water supply.

Evidence of the outside toilets is now hard to find, although perhaps the structure with black door, image left, just might have been one?

The tight street grid (below left) of ‘through terraces’ are topped and tailed by larger dwellings (below right), like mini castles protecting their two-up two-down terrraces (below centre) from some unknown threat.

The tiny front gardens are as varied as anything can be in an area of blanket listed buildings (grade II*), located in a Conservation Area, located in a World Heritage Site. Even these designations are not proof, however, against the modern townscape horrors of parked cars and wheelie bins.

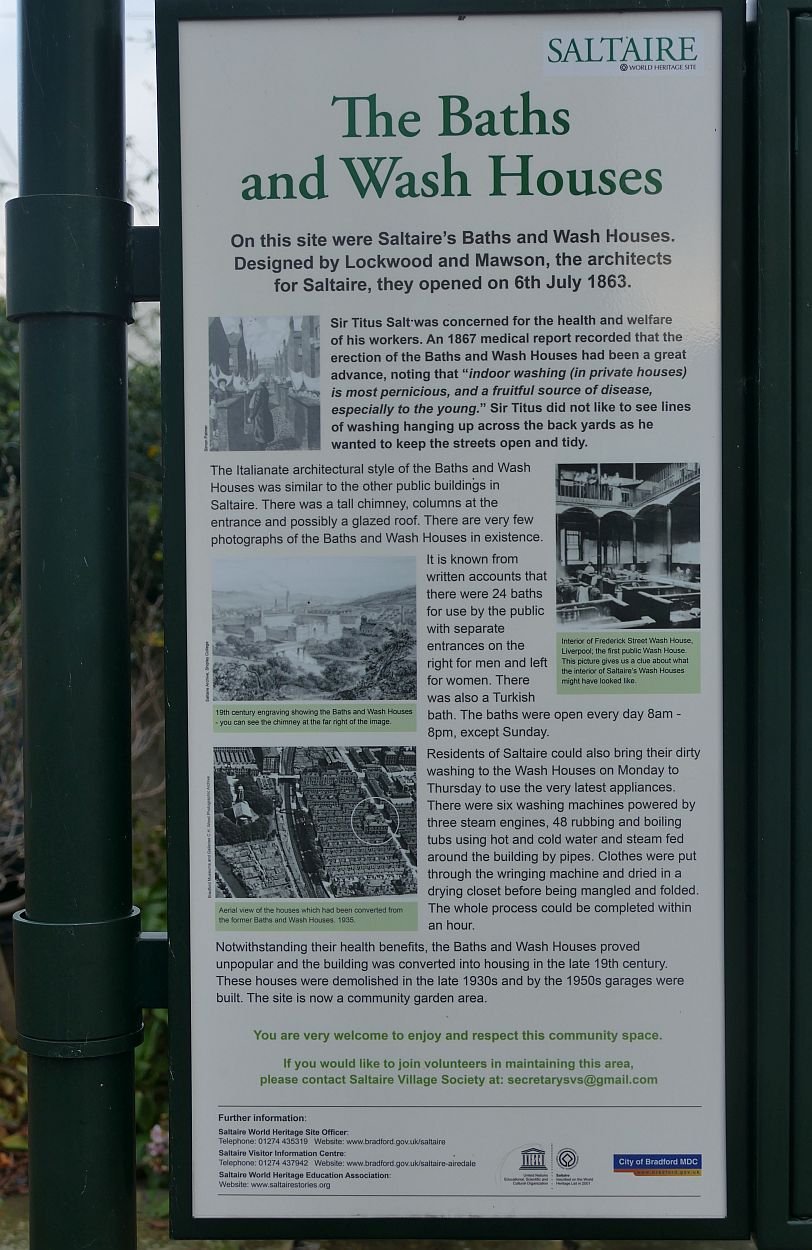

The housing areas were supplied with substantial bath and wash houses, but these were not popular. One suspects that the novelty of running water and gas heating in the comfort of one’s own home made lugging the washing down the street on a wet Yorkshire morning an unattractive prospect. The site of one such Bath and Wash House is marked with a well illustrated information board (below left) and the space is now planted up as a pleasant pocket park (below right).

There followed the addition of other amenities: the Congregational Church (now a United Reformed) (below left) and the Saltaire Institute (now Victoria Hall) (below centre and right).

There were also a school, a hospital (below left and centre) and alms houses (below right).

Were Salt’s motives purely philanthropic? Would his time, energy and money have been better sent improving working conditions for all, for instance through campaigning and legislation? Or did his model town show to best advantage what could be achieved, either voluntarily or by statute? We will return to this aspect later. What happened, one wonders, to employees who could no longer work in the factory through ill health or infirmity? The Alms houses are reported to have offered rent and tax free accommodation, plus a weekly stipend, but only for a maximum of 60 people. Was this sufficient? Were families thrown on the streets if the main bread winner died ‘in service’?

Other model villages have been accused of paternalism and even social engineering. (For instance, Helen Chance, ‘Chocolate Heaven to Tech Nirvana’, https://www.folar.uk/folar-talks). Chance and Terroir are not the only cynics. Wikipedia quotes David James (Oxford Dictionary of Biography)

‘Salt's motives in building Saltaire remain obscure. They seem to have been a mixture of sound economics, Christian duty, and a desire to have effective control over his workforce.’ James continues: ‘the village may have been a way of demonstrating the extent of his wealth and power. Lastly, he may also have seen it as a means of establishing an industrial dynasty to match the landed estates of his Bradford contemporaries.’

Does this matter, if 3,500 people had decent living conditions?

Today, after major regeneration in the 1980s, Salt’s building project has created a new town of World Heritage Standard, much of which consists of very desirable private residences. Property prices are low in Bradford, but Salt’s cottages sell for about double the price of similar sized property elsewhere in the City. Obviously location and architecture count for a lot, although this may be tempered by difficult parking and, as noted above, a heavily regulated environment.

But Salt left one legacy which still offers as much today - in terms of accessibility, health, social and environmental benefits - as it did in the mid 19th century. This legacy is Saltaire Park, now known as Roberts Park.

Opened in 1871, the 6 ha park was designed by William Gay. Gay was probably better known for his cemeteries but his parks, included Horton Park in Bradford (registered Grade II) as well as the Grade II Saltaire Park (https://www.parksandgardens.org/places/roberts-park-baildon).

Bordering the north side of the River Aire, Gay laid out the river side meadow as a generous, grassy space for cricket and croquet, bathing and boating and informal recreation generally. Making use of a slight slope behind, he created a promenade with bandstand overlooking the cricket ground, and serpentine paths winding through ornamental planting. Refreshment rooms were built into the bank below the promenade. A bronze statue of Titus Salt was added in 1903.

By the beginning of the 21st century, the Park was in need of some attention and a successful Heritage/Big Lottery Fund grant enabled a £1.3 million restoration project which was completed in 2010. Gay’s layout has been retained but the park now benefits from a new playground, rehabilitated Park shelters and lodge, as well as Gay’s - now mature - trees towering over rejuvenated planting and paths .

Cricket is still played, observed by Sir Titus himself and two of his alpacas, who appear to be checking the boundary to confirm four runs.

The project also included a replacement bandstand, as the original had been removed some time previously and its companion canons, one of which is reputed to have been fired at the Battle of Trafalgar, had been melted down as part of the war effort in World War II. The replacement artillery (below left) consists of two 19th century canons, produced in a Bradford Ironworks, although never used in anger. The bandstand is not only decorative, but multifunctional (below right)

Other significant restored features are the three, very decorative, park shelters (two examples below left and right) and the park lodge, rescued from dereliction and put to community use.

Gay’s now massive Corsican pines add grandeur and height to a site which lacks somewhat in level changes. Gay underplanted with hollies and one suspects that these have been massively reduced, controlled and managed to ensure tempting vistas within the park and views to and from the shelters (very welcome on a dreary December Sunday). Roses and magnolias must be a feature in spring and summer and the all-year-round mixed planting beds contributed to a very satisfactory winter walk. The restored promenade and serpentine paths make ‘access-for-all’ not just possible, but a real pleasure.

So why did Saltaire Park become Roberts Park? Many sources applaud Salt’s philanthropy, note that he was amongst the wealthiest of the Bradford textile ‘barons’, that he gave away perhaps half a million pounds to good causes during his lifetime, and that, although he did not invest in a landed estate as many others had done, he did provide his family with a comfortable family home (Crow Nest). At his death in 1876, his legacy was Saltaire model town, already famous for its humanitarian principles. But that was it; he did not leave his family any money. The estate went into administration in 1892 and was bought by a consortium of four business men, one of whom was Sir James Roberts. The mill and town retained Salts name but the Park did not.

Where did Salt’s fortune go? Textile prices were falling towards the end of 19th century, yet other mill owners survived. Was Salt a poor manager, incapable of technological change, or financial wizardry? Or did he put philanthropy (or his ego) before profit? I don’t know. Neither can Terroir comment on whether Saltaire had any long term impact on reform of working conditions or social security.

What Salt did leave, however, is Saltaire Park. Here is a legacy which keeps on giving, keeps on improving people’s lives and, thanks to enlightened management and the Lottery grant, probably benefits more people now than it has ever done before. Ironic about the name.

Final Offa

I wouldn’t blame you if you are thinking, ‘when will this walk along Offa’s Dyke end?’ We were thinking much the same as 2021 dawned and, five years after we started, there were still three days walking left to do!

This final section of the walk is formed by the Clwydian Hills which stretch from the village of Llandegla in the south to the resort town of Prestatyn – our final destination - in the north. It’s a continuous stretch of about 22 miles (35 km) by raven, but nearer 33 miles by the Trail (54 km).

This strip of sedimentary rocks (laid down in a warm sea over 400 million years ago), create a joyous, green, looping barrier between the industrial landscapes of north east Wales and the exhilarating geography of the rural Vale of Clwyd to the west. The range leaps from hill fort to hill fort and I’m reminded of an irregular pile of giant green cushions, trimmed with craggy lace and green chenille woodlands.

No doubt hill fort builders appreciated the more strategic and defensible attributes of the range, while trail walkers tend to concentrate on the inexorable challenge of a steep haul up (albeit rewarded by an outstanding view), followed by a knee crippling descent. Again and again and again.

Llandegla, at the southern end of all these ups and downs, was once a thriving community on one of the main drove roads connecting north west Wales to Wrexham and the English cattle markets. According to a village information board, the drovers once brought enough business to support 16 village pubs but, unsurprisingly, only two now remain in business. In many villages, one pub seems a miracle of survival, but perhaps walkers and tourists to this attractive area, and undoubtedly pretty village, are in sufficient numbers to enable a choice of hostelry.

Below: the church, cottages and Old Smithy are symptomatic of this attractive and historic village, but don’t believe the sign post.

Walking out of the village is deceptively easy, traversing well-watered pastures before commencing an easy climb towards the reality of the Clwydian Range.

We are spared from climbing Moel yr Accre and Moel y Waun - babies at just over 400 m (1,312 ft) - which lie to our south and east respectively, but soon begin the serious climb to Moel y Plas. Moel means a round headed hill and these high-ish but unaggressive, beckoning hill tops must have been a blessing for prehistoric peoples: the maps are pockmarked with cairns, tumuli and the afore mentioned hill forts.

The Trail continues in friendly mood and does not require a summit expedition for Moel y Plas, Moel Llanfair or Moel Gwy, the latter reaching 467 m (1,530 ft). We continue on at a gentle, undulating tramp around the 400m contour, until we drop down to cross the main road at Clwyd Gate. Our first day of the Clwydian Range has been leg stretching but thoroughly enjoyable.

By the time we return for the final push, it is early October 2021. Picking up from Clwyd Gate, our first round-headed hill of the day is Moel Eithinen, which we skirt, before a concerted attack on Foel Fenlli which we conquer with fresh-legged enthusiasm, scorning the bypass route, clambering over the hill fort ramparts, and striking a pose on the 511 m (1,676 ft) top height. The view of the fort ramparts, and the wider landscape is spectacular.

Above right: the rounded summit of Foel Fenlli, the slopes a patchwork of heather cutting to encourage grouse. Do grouse object to softer shapes, more in keeping with the curves of the landscape?

Below: the gentler environment of Moel Eithinen and (lower row, 2nd from right) the steeper slopes of Foel Fenlli; the path ahead of the hiker is about to cross the hill fort ramparts before climbing up to the very modern cairn on the summit. Lower row, far right: the view from the top.

Plunging down the far side of Foel Fenlli, we settle in for the tramp to Moel Famau, possibly the most famous Moel of them all and certainly one which we have both climbed before.

As the ‘top of the range’ (554 m or 1,818 ft), Moel Famau has, of course, become the honey pot of the Clwydian Hills. Car parking is reasonably generous, information signs abound (spot those right-angle loving grouse) and the access track is wide and smooth, making it a very accessible, biggish hill.

It’s a Saturday and a lot of people are enjoying themselves, trekking to the Jubilee Tower on the summit. Some slow significantly on the final assent and appreciate the occasional bench or pass on tips about a contouring alternative route!

The Jubilee Tower isn’t much of a reward for the climb and has had a cyclical history of refurbishment and neglect. The Jubilee in question marks the 50th year of the reign of George III, so the structure has been around since 1810. Inevitably location makes restoration expensive.

By now, the clouds have descended and although the children are enjoying hide and seek in the misty atmosphere around the Tower, the view from the top has vanished. Time to press on.

The trail now dips down a little and takes us through a long stretch of undulating uplands. We traverse Moel Dywyll, and look back to the Jubilee Tower (right). But our target for the day is Moel Llys y Coed which, at 465 m (1525), stands guardian over the mystical sounding Moel Arthur (a smidge lower and finally a name that one of us doesn’t struggle to pronounce).

It seems that ‘one of us’ has never before visited either of these majestic hills and, on breasting nearly-the-top of Moel Llys y Coed, the view of Moel Arthur takes one of us’s breath away. There, across the valley, lies a perfectly circular, fort-crowned dome of green and brown magic; the Glastonbury of North Wales, complete with bewitched rowan. It is possible to climb Moel Arthur, of course, but the Trail elects to go round and, as it’s started to rain, we elect to go with it and postpone the Arthurian experience to another time.

We are nearly through the big Clywdians now although we still have a long stretch of commercial conifer forestry to negotiate (Coed Llangwyfan), another hill fort to inspect (on Pen y Cloddiau) and a distant view of Moel y Parc to enjoy, before we descend down into the valley of the River Wheeler (Afon Chwiler), and cross over to the village of Bodfari. By now our numbers have swelled to four individuals, as part of Terroir North has joined us, although the most important member of the expanded team is Pixie the dog.

Ten Terroir legs are now walking up through Coed Llangwyfan and scaling the heathery slopes of Pen y Cloddiau. Pixie adds a new dimension to the expedition; her view is distinctly lower level and enhanced by her olfactory skills, while her companions are on constant alert for livestock and the need to reel back the extending dog lead.

Before we descend to Bodfari, we are treated to a memerising view: a distant glimpse of our final destination. There in the haze lies the Irish sea, complete with windfarm and, ornamenting its edge, the seaside town of Prestatyn.

Beyond Bodfari, which sounds more Italian than Welsh, the Clwydian Range subsides into a lower ridge of undulating, agricultural and rural domesticity but with some high points, literally as well as figuratively. These hills will lead us all the way to Prestatyn. Slopes are steep but the climbs are short with top heights generally less than 250 m (820 ft) but hill tops still abound in tumuli and the occasional hill fort.

Left: bench in the bizarrely named village of Sodom

Once a fishing village on the edge of the Irish Sea, between the Dee Estuary and Colwyn Bay, Prestatyn - our final destination - was transformed into a seaside resort with the coming of the railway in the late 1840s. As the town grew, the urban area spread inland until it was finally halted by the Clwydian Hills - a surprisingly steep finale, about a mile from the sea.

After 177 miles of inland, rural walking, the descent into a seaside town comes as an enormous shock. We feel totally incongruous, marching down the High Street in walking boots and anoraks, rucksacks bumping on our backs. Buckets and spade shops, cafes, pleasure gardens, convenience stores, pubs, holiday chalets and bungalows, feel totally divorced from, and lacking connection to, the hills and vales, orchards, meadows and upland pastures, bridges, earthworks, rivers and canals, villages and towns through, over and up which we have intermittently plodded for the last 6 years.

Strangely, the beach seems less bizarre. Unsurprisingly it is deserted, late on an October afternoon, and the wide, windswept, damp sands, the promenade seats, and the seaside sculptures create a surreal effect which suits our mood. And it is our mood which catches us unawares. We are ridiculously elated. One of us stands in the sea with boots in one hand and walking pole in the other, raising them in salute to the border lands through which we have travelled.

There is really only one way to celebrate our arrival. It’s 6pm but the ice cream café is still open and dogs are allowed. We purchase one vanilla and two cones of rhubarb and custard ice cream. Pixie is not impressed.

Stunning Offa

It’s mid August in 2020. Wales has finally opened its borders and English based Terroir has travelled north west, desperate to get back onto Offa’s Dyke. The support vehicle has delivered three of us to the exact point on the Shropshire Union Canal tow path where we ended our walk eight months previously, on a carefree, Covid free, wet and windy January day. Ahead of us lies some 15 miles of the most spectacular walking on the Offa’s Dyke Trail. The weather is hot and our packs are heavy with water and sun block, in addition to the usual supplies. The frisson of expectation is tinged with apprehension. I also have a nasty feeling this blog may get written in the dramatic present tense.

A short walk along the ‘Shroppie’ brings us to the southern end of a UNESCO World Heritage Site: the Pont Cysyllte Aqueduct. This puts this section of the Offa’s Dyke Trail in the company of the City of Bath, Blenheim Palace, the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, Iron Bridge Gorge and, of course the ‘Frontiers of the Roman Empire’ along Hadrian’s Wall. Top marks to the National Trails for getting at least two UNESCO badges.

The UNESCO website entry is obviously written by a civil engineer and refers to the aqueduct as ‘Covering a difficult geographical setting’. I would accept ‘challenging’ and, indeed, embrace ‘spectacular’ but to me, ‘difficult setting’ reduces Telford’s ‘masterpiece of engineering and monumental metal architecture’ to the level of a fractious child (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1303/).

Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pontcysyllte_Aqueduct) adopts a far more practical approach by explaining the economic context which prompted the building of the aqueduct, and yet left the canal unfinished. What is now known as the Llangollen Canal was supposed to be an essential section in the proposed Ellesmere canal network, connecting the River Severn with Liverpool docks. A geographically less ‘difficult’ and cheaper route was abandoned in favour of the Vale of Llangollen crossing, a circuit which would allow commercial access to the coal fields of north east Wales. Unfortunately, the predicted revenues did not materialise and the completion of the stunning aqueduct, in 1805, is reported to be about the last major piece of construction in this unfinished engineering matrix.

Due to its links to the Shropshire Union Canal, the Llangollen arm continued to carry limited commercial traffic into the 1930s but was formally abandoned in the 1940s. The aqueduct was retained as part of a water feed to the Shroppie, and reopened to a new world of pleasure craft some 40 years later.

The aqueduct is basically a very long metal trough, supported on iron arches and hollow stone pillars. As a pig trough, it could probably feed and water nearly 1,000 pigs simultaneously, or could be converted to about 170 bath tubs laid end to end. The tow path runs the length of the trough and a substantial metal railing protects path users from tumbling the 125 ft (30 m) to the valley below. It is not an experience for the feint hearted, whether on foot or aboard a narrow boat.

Because of this challenging setting, the official Offa’s Dyke Trail offers two options for crossing the River Dee at this point. Two of us go by aqueduct tow path and the third takes the valley route. Apparently, alternative photographs from the valley bottom are crucial!

From Trevor Basin at the north end of the Aqueduct, the Trail crosses the wooded and pastoral Dee valley before starting a steady climb up and out of the Vale of Llangollen. Our way is about to explode into one of Britain’s the most dramatic and surprising landscapes. We are about to enter the Carboniferous limestone world of the Eglwyseg and Esclusham Mountains.

The hyperbole is not just mine. Described as ‘an iconic landscape of truly outstanding scenic and visual quality’ (https://www.clwydianrangeanddeevalleyaonb.org.uk/projects/the-dee-valley/) this area is designated an Area of Outstanding Beauty. What is so special about this extraordinary area? Let us take you on a photographic tour and give you a taste of this bizarre landscape.

Leaving the road above Trevor village, the Offa’s Dyke Trail heads off through the gateway to Trevor Hall and Trevor Hall Wood. The battered formality of this entrance comes as something of a suprise, but in hind sight, it presents a wonderful, Narnia-esque, entrance to the remarkable landscape which awaits.

Below:

left - climbing upwards through Trevor Hall Wood

right - emerging at the top.

We climb through the wood, a significant portion of which has been converted to exotic conifer plantation, and emerge to admire the view before joining a track and then a metalled road. This latter would normally spell disappointment, but not today. What a privilege to have access to this unexpected landscape (aptly named, at this point, The Panorama): part desert, part scree, part cliff, part guardian of the wooded river valleys below (the Dee and the Eglwyseg), part pasture, part scrub, part alien.

There is, however, a great deal more to this landscape than scenic wonder. Other designations also apply: a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and a Special Area of Conservation (SAC). Specialist wildlife love a stressed landscape such as this free draining, lightly grazed, alkaline, and to humans, perhaps, unfriendly environment. Here we have the calcerous dry grasslands, the limestones screes and rocky slopes. Here are rock roses, musk thistles, and autumn gentian. Here grows the rare Whitebeam - Sorbus anglica - and here the rare Welsh hawkweed (Heiracium cambricum) has been recorded. Later, we will find contrasting and extensive areas of dry heath.

Another designation also gives the lie to the phrase ‘unfriendly environment’. This is a Landscape of Special Historic Interest and humans have made use of this area from at least the Bronze Age. The Dee valley was fertile and well-watered of course, but the uplands may well have offered summer grazing, ceremonial sites and, by the iron age, defended settlements (https://www.cpat.org.uk/projects/longer/histland/llangoll/vlland.htm) ‘Hard’ evidence of Medieval society - including wealth, christianisation and politics - is much easier to find and a couple of atmospheric ruins deepen the landscape’s sense of mystery. Madog ap Gruffydd Maelor, 13th century Prince of Powys, built Valle Crucis Abbey, a Cistercian foundation, later dissolved by Henry VIII in 1537. It’s less than a mile off piste, hidden from view, but well worth a visit.

In contrast, Castell Dinas Brân (left) is a highly visible symbol of Welsh history and partiotism, probably built by Gruffydd Maelor II (Madog’s eldest son) on a previously occupied (probably from the Iron Age onwards), and very prominent, hill top above the town of Llangollen.

Today, this landscape is beloved by hikers, cyclists, climbers, naturalists, archaeologists, historians, landscape lovers and sheep, yet on this hot August weekday it feels deserted and other worldly.

We are not entirely alone, however (below): cycling and farming provides the most obvious signs of life on the day of our visit.

Walking through this landscape is suprisingly tough, however. It’s hot, the scenery is mind blowing, there is precious little shade, the walking is either hard-on-the-spine highway or narrow-stony-track and the few streams we cross - plunging down and up again to cross their narrow valleys - are nearly dry. It is also a long, long section.

At the appropriately named Worlds End, we drop around 50 m (160 ft) to cross a steep sided valley and then start a 65 m (210 ft) climb between the Eglwyseg and Esclusham Mountains to reach our top height for the day (394 m or around 1,290 ft). The map shows remnants of the long established mining activity all around us although they are hard to pick out, even on these bare hill sides.

The Trail is rocky and bare, but life is all around. Above us, a single tree, beside us a lime loving musk thistle or a rare grayling butterfly, below cyclists, and the verdant vegetation and farmsteads of the valley bottoms.

We have walked through this startling landscape for four hours - tired but never tiring of the view - when, with an extraordinary jolt, the Trail suddenly segues into another exceptional, but totally different topography and habitat: the dry heath which we spoke of earlier.

To be honest, by this time, we are suffering from mental overload and physical exhaustion. Our water supplies are running low and we take a break beneath scant shade before we attempt to cross the sea of heath and bracken. An even more senstive environment than the stony mountain sides which we have just left, the Trail is now protected by a makeshift board walk, or paved with enormous recycled slabs which remind me, rather ominously, of grave stones. Sheep are safely grazing, but some areas appear to be managed as grouse moor, so the grouse may also view the slabs as a bad omen. The heather - at the peak of its floristic beauty - is very easy on the eye, but the slabs and boards are even tougher to hike over than the limestone tracks. It looks marvellous, but we are plodding on, silently wondering when it will all end.

But the heath does end, as abruptly as it started and, with a sigh of relief, we step into the shade of Llandegla Forest. The respite is short lived, however. This is a commercial forest with row on row of identical, exotic conifers and very limited ground flora. The track is, in parts, an ankle breaker, the mountain bikers are manic fellow travellers and the clear fell operations make paving slabs and heather look like a stroll in the park.

But Llandegla Forest means we are very close to Llandegla village where the support vehicle will be waiting for us. In normal circumtances this soft path, through mixed woodlands and fields, would be a delightful way to end a day’s walking. For the first time in my life, however, I am really struggling to put one foot in front of another. The final stile is a slow nightmare. There are steps up to the road which seem impossibly steep. I am nearly defeated by having to move my body into the back of the car. But I do it. Without help. And an hour and two pints of water later, I can move again - almost normally.

Another Offa

Nearly a year ago, in the days when we thought Christmas 2020 would happen, we posted a couple of blogs on the Offa’s Dyke National Trail, which we had been section walking since 2015. After two episodes (which included passing the Trail’s half way mark), we decided to give you all a break, and moved on to other topics, but we feel the time has come to revisit the Welsh border lands and pick up the threads of our story once again.

We left you (Blog 6 on 3rd December 2020) with camera failure somewhere near the Breidden Hills. We had walked through the Royal Forestry Society’s Leighton Estate, south east of Welshpool, climbed the long slope to Beacon Ring Hill Fort, shrouded in trees, and then slid down over a thousand feet (342 m to be exact), to the Severn Valley below, crossing the swollen but sluggish river at the grade II listed Buttington Bridge, a mere 68 ft (21 m) above sea level. The Trail then appears to take leave of its senses and threads its way, perilously, through a busy, industrial scale dairy operation. Thankfully, the Breiddens, topping out at a similar height to Beacon Ring make an arresting back drop to both the tankers and the Severn’s lazy journeyings.

The Severn-side section of the trail has been diverted since our antediluvian guide was written and, presumably because of flood risk and the current lack of a Noah’s ark, the way now takes walkers along a short stretch of the Montgomery Canal, which hugs the very western edge of the Severn flood plain, following the contours just below the 80 m mark (262 ft).

Leaving the canal, the Trail climbs onto substantial flood defence dykes which skirt the Severn’s convoluted meanders. Most such structures are stark, grassy banks within wet pastures,

but this delightful example (image right)

protects a garden, which the owner has allowed, or encouraged, to spill out onto the

Dyke itself.