White Stuff

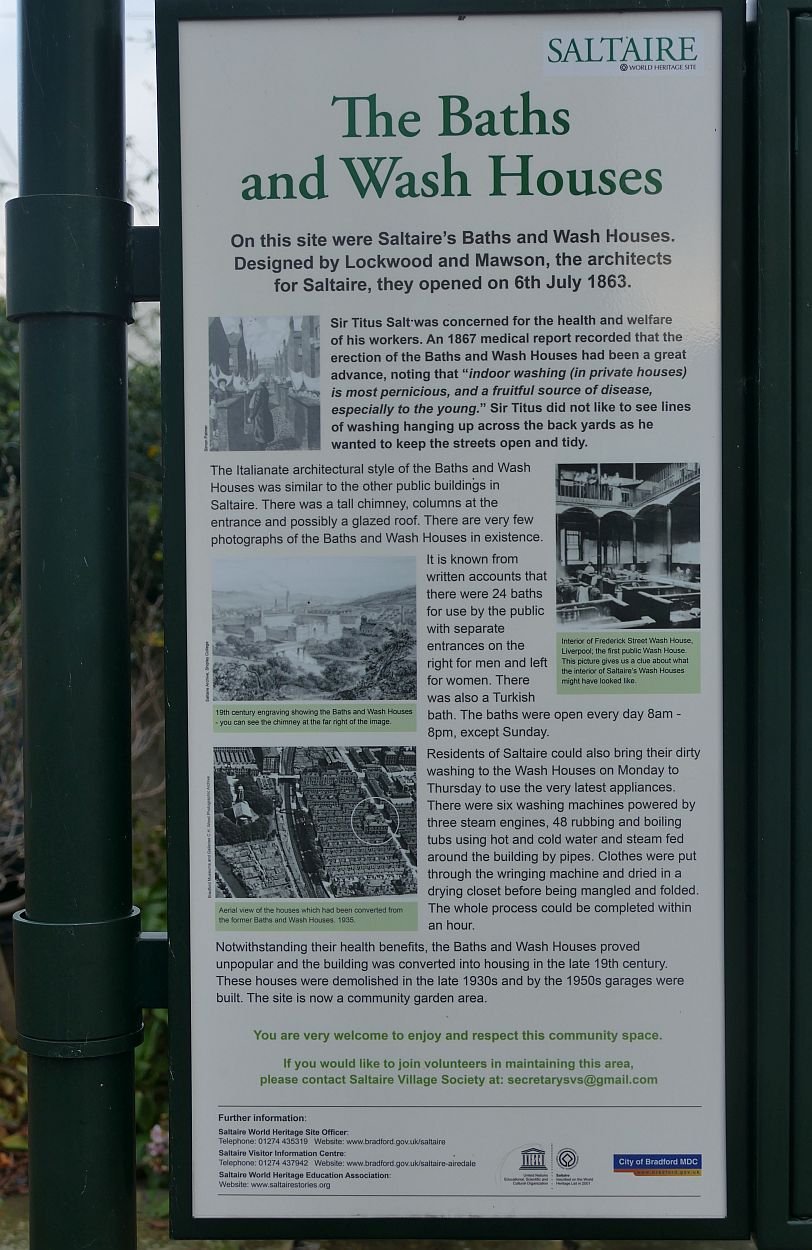

Cornish holidays: beauty, wildness, mystery. Crashing seas, coves, beaches, wind-swept uplands, lighthouses, fishing villages, smugglers, sea shanties, tales of adventure, romantic ruins and mineral extraction. Yep, it’s all part of that Cornish allure.

“Metal mining, especially for tin, is Cornwall’s greatest and most romantic industry…” (Richard Stanier, Cornwall’s Industrial Heritage, 2005). Where’s the romance in shanty towns, arsenic poisoning, deep mining and limited life expectancy (Blog 71)?

Well, precious little of course, but when industry becomes heritage, perception changes. Those “hundreds of roofless engine houses across the landscape” (Peter Stanier again) are an alluring hint of bygone times. But, as we noted in the ‘Tinners’ blog, tin mining not only left a landscape of iconic industrial archaeology, it also left very little obvious waste.

Not so Cornwall’s other “massively important” (more Stanier) mineral industry – China Clay. China clay extraction and processing changed the rural landscape from green to an often startling white, either as holes in the ground, or as conical heaps (sky tips) of waste materials. It had an enormous visual impact over a huge area. Characteristic of many areas of Cornwall, and yes iconic, but I suspect few find it romantic.

The internal environment created by China Clay processing could be very different, however, and the lives of the workers, though tough and physically exacting was probably very different to the life of a tin miner.

In Terroir’s school days, China Clay was always mentioned in secondary school geography lessons, although I have no memory of being told of its use in ceramics, merely as an additive to fabrics and toothpaste. I don’t think historical geography was well regarded then. I do remember references to ‘rotting granite’ which we thought was highly amusing. So a very quick summary of the history of china clay may be appropriate.

China clay or kaolin results from decomposition of feldspar in granite. The Chinese knew its ceramic properties centuries before Europeans got a handle on it. In Cornwall it had been used as a building material until a Plymouth Quaker apothecary, one William Cookworthy, produced ‘hard-paste’ porcelain and patented the mix in 1768. Naturally, he opened a pottery. Cookworthy’s partner later tried to extend the patent but the guys from Staffordshire, led by Josiah Wedgwood, broke the monopoly. Other uses were also found for kaolin and extraction expanded rapidly.

China clay was valuable enough to support a system based on extraction of vast quantities of raw material, followed by lengthy processing, to produce only a small amount of the final clay product. Around 90% of the material quarried is discarded as waste. Although the landscape impact was enormous, the processing details can be surprisingly beautiful. Our thanks to the Wheal Martyn Clay Works Museum (right) for showing us the processes involved and the technology created to undertake the journey from ‘rotting granite’ to porcelain, or indeed, paper and toothpaste.

The quantities required, and the softness of the raw material, meant that a flow of water was the simplest way of removing the kaolinised granite. Gravity fed water flows were soon replaced by hand held hoses, which later developed into the high pressure, serpent like, ‘Monitors’.

The clay slurry had then to be pumped from the pit to surface level. Initially water wheels provided the energy until replaced by steam powered pumps.

At Wheal Martyn, waste material – quartz, sand and rock - which couldn’t go up the slurry pump shaft, was sent up by skips on an inclined tram road. Here was the first load of spoil needing to be dumped.

Right: self tipping skip waggon, image courtesy of China Clay History Society

The slurry of clay, sand and mica, went to the sand ‘drags’, a system of gently sloping channels, which allowed the sand to settle out - and this spoil was discharged to the river.

Next the mica drags performed a similar job for the smaller mica particles, which were also discharged to the river, often mixed with a smidgeon of clay slurry; the rivers ran white as a result.

At Wheal Martyn, the pure clay slurry then entered the Blueing House (still with us?), was sieved through a wire mesh to remove leaves or other materials which may have dropped in, and a blue dye could be added, to hide any discolouration which would have reduced the value of the clay.

Next, the slurry flowed into the settling pits and clear water was drained off as the clay dropped to the bottom over a number of days. Once the clay was the consistency of single cream, the slurry was run into the settling tanks and the process repeated until the slurry was as thick as clotted cream. This could be a slow process.

Finally, the ‘cream’ flowed or was trucked into the pan kiln. This was lined with porous pan tiles which allowed heat from flues beneath the floor to rise upward and dry out the clay. At least the pan tiles at Wheal Martyn were made from waste clay and sand, but we doubt this made much of a difference to the volume of waste material to be dicarded.

The pan kiln at Wheal Martyn is remarkably well preserved and imaginatively interpreted. It reminded Terroir of hand made brick works, where the craft and skills of the individual brick makers belies the external mayhem of clay winning outside. Similarly at Wheal Martyn, the pre-mechanised, human scale of the clay processing presented craft skills and human endeavour which stand at odds with the large scale business of hauling china clay out of the ground.

The final product (in block form, or packed in casks or sacks) was stored in the linhay (pronounced ‘linny’), before dispatch to customers by road (impacting on the bypass-less local towns) or rail.

Image right: China Clay History Society

The human element was largely made up of men and boys, although women were employed to scrape clean the bottom and sides of air dried clay blocks.

Images above: China Clay History Society

The techniques shown above did not last, and increased mechanisation did nothing to reduce the quantity and quality of waste, stacked around the clay pits.

Images above: China Clay History Society

The industry continues today, of course. Many Victorian companies amalgamated into larger units, but around 70 producers still existed prior to WWI. Three of the largest - West of England and Great Beam Clay Co, Martin Brothers, and the North Cornwall China Clay Co – were amalgamated in 1919 to become English China Clays and, through further mergers and reorganisations the company survived the lean times before and after WWII. In 1999, the core of the company was purchase by Imetal, now known as Imerys. It’s signs are everywhere throughout the Cornish China clay territories.

Attitudes to waste disposal and restoration are, however, finally changing.

The most famous restoration scheme – The Eden Project – opened in 2001: “We bought an exhausted, steep-sided clay pit 60 metres deep, with no soil, 15 metres below the water table, and essentially gave it life.” (https://www.edenproject.com/mission/our-origins). The projects mission is to “create a movement that builds relationships between people and the natural world to demonstrate the power of working together for the benefit of all living things”. It is a significant player in Cornish Tourism.

Schemes in other areas have been less ambitious but our overwhelming experience of the 2022 Cornish China Clay landscape is of gentler land forms, of colour schemes now in a palette of browns, greens and yellows, of native species, grassy areas and new woodlands. Of ‘come in’, rather than ‘keep out’. It’s not perfect. But words such as ‘healing’ and ‘biodiversity’ come to mind. The iconic Cornish Alps have largely gone but a symbolic sky tip or two remain, although these, too, are turning from grey and white, to brown and green.

Is it romantic yet? Terroir thinks not. But we are hopeful that, one day, derelict 21st century wind turbines will be considered romantic - that is if we and the planet make it that far.

The Pool of London

On crossing London Bridge, one of Terroir’s parents would always look east to see what shipping was in the ‘Pool’. The Pool of London was always a bit of a mystery to the offspring. It looked just like a normal stretch of tidal Thames to us. But for a woman who had commuted to work in the City of London before, during and after WWII, and who had watched the bustle and vibrancy of the Thames wharves and docks from the top of London buses, the Pool of London would always hold a special place in her Londoner’s heart.

More recently – much more recently - Terroir took a visit to the Tower of London to see how the Superbloom was coming on (image right). More of that in future blogs, but the walk along the north bank of the Pool, from the Tower of London to London Bridge was like stroll along a historical transect from the medieval to the modern.

The Pool of London played an integral part in the growth of the City of London and has a long history of commerce, crime and social issues. Wikipedia gives a good summary. Originally, the Pool of London was the name given to the stretch of the Thames along Billingsgate. This is the stretch you can see from London Bridge and where HMS Belfast is moored.

And this was where ‘all imported cargoes had to be delivered for inspection and assessment by Customs Officers, giving the area the Elizabethan name of "Legal Quays".’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pool_of_London and https://en.wikipedia.org)

London Bridge, itself, prevented shipping from going any further up river but, as both overseas and ‘coastal’ trade increased, the concept of the Pool spread downriver, eventually reaching the Rotherhithe/Limehouse area. By the end of the 18th Century, with the slave trade and Caribbean colonies in full swing, the Pool could no longer cope with the volume of trade and shipping, and the first, off-river dock was constructed specifically for the West Indian trade. Other off-river docks followed, of course. The whole maritime commercial area, including the Pool, remained viable right into the 1950s despite damage caused during the Blitz.

Terroir walked along the north bank of the Pool of London (now part of the modern Thames Path) from the south west corner of the Tower of London to London Bridge. The map extract, below, shows what it all looked like in 1873. The Great Ditch of the Tower of London is just visible on the right, London Bridge on the left.

All map extracts reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland' https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

Sugar Quay Wharf

Known as the Wool Quay in the 13th century, this wharf was the location of a building which was key to the Port of London: a custom house. In this case it was used to collect duties on exported wool. There were a number of iterations of this Custom House: a new building, overseen by the then Lord High Treasurer, William Paulet, was built around 1559, but was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666.

Christopher Wren designed the replacement, which was constructed in the early 1670s, but fire hit again in 1715, necessitating a fourth rebuild. This one managed to function, unsinged, until the early 19th century and then, yes, a fire started in the house keeper’s quarters where, apparently, both spirits and gunpowder were stored (really?) and Customs House No 4 exploded. And people criticise modern Health and Safety Regulations. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sugar_Quay

By 1934, Wikipedia reports that the Batavia Line, which ran a steam ship passenger service between Rotterdam and London, was berthing its ships here. In 1970, Terry Farrell designed an office building for Tate and Lyle, but the final break from both shipping and sugar came with its conversion to a mixed use development in the 20 teens. Or maybe that statement isn’t quite true: the developer – CPC – was owned by the Candy Brothers.

Custom House

Custom House No 4 was doomed before it exploded. London’s maritime trade was booming and a larger Custom House was commissioned for the site adjacent to the one described above. Bear Quay, Crown Quay, Dice Quay and Horner's Quay were all subsumed by the new build, leaving a single Custom House Quay or Wharf.

Designed by architect David Laing, the new Custom House was completed in 1817. The building contained warehouses and offices, and the basement cellars (fireproofed) were used to store wine and spirits seized by the revenue men (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Custom_House,_City_of_London).

The Custom House curse had yet to be appeased, however, and the building partially collapsed in 1825, when the timber pilings under the building caved in. Wikipedia reports that the building contractors “had grossly underestimated the cost of the work and had started to cut corners. The foundations were totally inadequate” and “questions were asked in Parliament”. Familiar? After rebuilding, no further disasters seem to have occurred, until the east wing was destroyed in the Blitz. It was later rebuilt behind a re-created historic façade.

The former Quays have gone but the building remains. It is listed grade I. Plans to convert the building into a hotel were rejected in 2020 and the project went to appeal early this year.

Billingsgate Market

As a market, Billingsgate started out as a general wholesale supplier of corn, coal, iron, wine, salt, pottery, fish and miscellaneous goods, and it wasn’t until the 16th century that it became for specifically associated with fish (https://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/supporting-businesses/business-support-and-advice/wholesale-markets/billingsgate-market/history-of-billingsgate-market)

And it wasn’t until 1850 that the first market building was erected, to replace an array of market stalls and sheds. It quickly proved to be inadequate – this was the 19th century, after all, an era of constant change and expansion – and a new market building was erected in 1875, designed by City Architect Horace Jones and built by John Mowlem and Co.

Just as Covent Garden’s real estate was released when the Fruit and Vegetable Market moved to more spacious and accessible premises in 1974, so the fish market was removed to Docklands (the Isle of Dogs) in 1982. The Pool of London building – listed grade II - remains beside its Grade 1 Custom House neighbour, and was refurbished for office use by architects Richard Rogers. It is now a hospitality and events venue.

Grant’s Quay Wharf

We’ve called this section of the water front Grant’s Quay Wharf simply because this name features on one of the City of London’s signs.

From studying the historic maps – there is an excellent sequence at https://theundergroundmap.globalguide.org/article.html?id=34336&zoom=16&annum=2022 – this area appears to have resisted major redevelopment until the first half of the 20th century. 19th century maps appear to show a succession of narrow, bonded warehouses. Their northern elevations abut Lower Thames Street and cover the site of St Botolph's, Billingsgate, a church destroyed in the Great Fire of London and never rebuilt. To the south, the warehouses are just a road’s width away from the riverside quays and wharves with which they were intimately linked. Names include Fresh Wharf, Cox’s Quay, Hammonds Quay, Botolph Wharf, Nicholson’s Steam Packet Wharf, and at the eastern end next to Billingsgate Market, an ominously named residential street called Dark House Lane, which links to Summer’s Quay stairs.

By 1950, much has changed but the area still appears to be a working wharf. Not so today. The area is now a rather uncoordinated and largely uninspring development, which does little to reflect the lives and times of its riverside forebears.

Church of St Magnus the Martyr and London Bridge

Walking the Thames Path to London Bridge, you would hardly know that the parish church of St Magnus the Martyr is still squeezed in between the Bridge and the west end of the developments described above. As with St Botolph’s, St Magnus’ church was also destroyed in the Great Fire but was rebuilt by Wren in the 1670s and 80s.

Glance north as you approach the bridge and you will see the church spire fighting for vertical supremacy with the Monument, lamp posts and modern buildings.

The end of our historic transect reminds us of the importance of stairs in Thames-side life: stairs to reach the Watermen who ferried passengers to and fro, and up and down the river. Stairs which enabled mudlarking at low tide. And now a modern flight to enable Londoners and visitors to reach the Thames Path, its cafes, its views and its historic treasures.

Modern access between London Bridge and the northern riverside had been problematic for many years, but an elegant solution, in the form of a cantilevered, stainless steel, spiral staircase (designed by Bere:architects) was opened in 2016 and has revolutionised the Thames Path in this area. An honourable addition to the more traditional Thames stairs.

A Passage through Lyon

How much can you tell about a town through tourism?

When asked what we were going to do in Lyon, one of us replied, ‘sightseeing, eating and sleeping’. Another of us read a very out-of-date guide book before we left, but that was the sum total of our preparation.

So part of our plan for our two and two half days’ visit was made through the lens of the Tourist office, which provided us with maps, a tourist ‘access most areas’ card and a mini guide to what ‘Only Lyon’ suggested were the must-see sights. Thereafter it was all down to personal choice, based on the Tourist Office menu and our own particular interests. Did we achieve our goals and what did we learn about Lyon? As tourists we did well: ticks for enjoying ourselves, for sightseeing and for eating (as ever, sleeping was postponed). But what did we learn about Lyon?

Our first lesson is that some things in French Society haven’t changed. A lot of places were closed on Monday, and Tuesday wasn’t a great day for post pandemic museums either. So personal choice and the tourist map featured early: two wide, sinuous rivers, a lot of cityscape exploring and one enormous park.

That Lyon is central to France is pretty obvious from the map. So is the fact that it is on the confluence of two significant rivers – the Rhône, and its less well known, and harder to pronounce neighbour, the Saône. If we had gone to any of the five museums dedicated to the history of Lyon, including the specialist stuff on the Romans, the Gauls and Christianity, then one might miss the fact that around 29 BC Marcus Agrippa set up the extraordinary network of roads (the Via Agrippa) which connected Roman Lyon (known as Lugdunum) to pretty much every part of what is now France. This is ‘Asterix’ territory and one suspects that Obelix was giving Agrippa grief. We also suspect that the use of BC is no longer PC, but as Christianity was also an important part of Lyon’s history, I hope we will be forgiven. Today, Lyon is still a hugely significant administrative, economic and financial centre.

So our early walks through Lyon, dictated by the location of railway station, hotel, rivers and park introduced us to the eastern banks of the Rhone and the post medieval city. Here is grid pattern cityscape, divided into administrative arrondissements and smaller local communities with their own local characteristics. The built environment is dense and angular too, like closely spaced cardboard boxes on end, decorated in the classic style of French domestic architecture, with the occasional modern redevlopment. Small open spaces appear at fairly regular intervals but larger parks are few and far between.

Of course, the French are comfortable, and very creative, with ‘hard’ open spaces and we saw some well-used and much appreciated areas with minimal ‘soft’ landscape. We could understand why the riverside water play was closed, but its appeal to youngsters on a hot summer’s day was obvious.

The exception to the small city green space is, of course, the Parc de la Tête D’Or which sits in a curve of the Rhone to the north of the centre ville. A classic in European Park provision, this once private landscape was purchased in 1856 to create a ‘nouvel et vaste espace’ for the people of Lyon.

It took paysagiste Denis Bühler 5 years to create this ‘manifique parc à l’anglaise’. Its mix of wide grassy spaces, lake, lake side walks, woodlands, botanic gardens and small zoo provide an eclectic mélange of landscape and recreational options. Imagine our surprise when none of the cafes was open. The Swiss duo of Denis and his brother Eugène Bühler created parks throughout France in the middle and late 19th century, including Lyon’s Jardin des Chartreux on the left back of the Saône immediately to the north of Lyon’s old town.

Generations of fallow deer have grazed the Parc de la Tête D’Or and have now been joined by a small zoo including giraffes and a large number of rescue turtles (see images below). The variable beige colour of the turtles (row 2, centre image) is not natural but due to a heavy, overnight, fall of Saharan dust. Those that stayed out all night are rather obvious.

Park trees include a couple of massive Taxodium distichum (swamp cyress) with their characteristic ‘knees’ poking up along side the main trunk. Those planted so generously around the United States Embassy in London, are mere toddlers compared with these. Planes are a hall mark of the Park and one of the oldest has been retained as a natural sculpture, close to the lake. More traditional statues are also a feature, as are the splendid gates which lead out on to the Avenue de Grande Bretagne. Madame is probably just doing some stretches (bottom row, right) but we prefer to view her as a modern day ‘Asterixe’

The narrow Presqu'île between the Rhône and the Saône (below left) forms a long narrow tongue dividing the mass of modern day Lyon on the east bank of the Rhône from the older medieval town on the west bank of the Saône. It is a busy area, and hosts the extensive open space of the Place Bellecour (home to the Tourist Office and an equestrian statue of Louis XIV, below right), Lyon’s other large railway station (Gare de Perrache), and numerous churches, museums, public buildings, cafes and restaurants. According to the tourist map, pretty much the whole area is designated as a Shopping Zone. This is tourism, I suppose.

The southern tip of the Presqu'île lies at the confluence of the two rivers. It’s somewhere you feel should go, but if your tourist programme doesn’t feature the Aquarium and the two museums located in this area, we get the feeling that it’s slightly off the beaten track. Most tourists will do as we did and press on over the River Saône to enter Vieux Lyon.

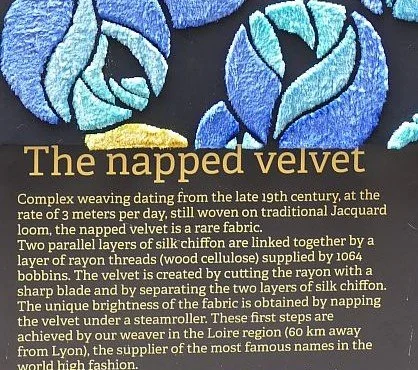

We mentioned in last week’s bog that Lyon is a silk city and it all started in this medieval town, perched under the hills which pinch the Saône into a tight curving valley before it finally exits into the Rhône. Here in Vieux Lyon are all the characteristics of an old town – narrow winding streets, small squares, medieval buildings, quaint shops and a mass of cafes and restaurants full of visitors.

Here too are Lyon’s famous Traboules, covered passageways which ran through the buildings and internal courtyards to link one street with another. Thought to have been first constructed in the 4th century, they provided short cuts to the river, to collect water, and later to transport textiles from workshops to merchants and ships by or on the river. They were probably use for silk workers’ meetings and, later, by the Lyon Resistance during WWII. They are spooky, often dark, and are intimidating to people (like us) who have a deeply ingrained sense of where we can and can’t go. Despite looking so private and providing intimate access to residents’ front doors, they are freely accessible to all.

Silk became a significant part of the Lyon economy from the 15th century, but the industry waxed and waned for the next 500 years. The Silk Workers House, one museum we did manage to gain entry to, charts the history and technology of silk and has an extraordinary working display of the Jacquard loom which Wikipedia describes as ‘a mechanical loom that rapidly industrialized the process of producing silk’. Although the brocades and damasks produced by this method are stunning and the technology feels way ahead of its time – a punch card system installed on the top of a wooden loom, dictating the pattern to the weaver – the rate of production was around a third of a metre a day, and the financial risk lay entirely with the weaver.

We also went to the Lumière Cinema Museum, the Resistance and Deportation History Centre and the the Fine Arts Museum.

But there are huge holes in our knowledge of, and appreciation of, the city. Just a peek at the silk industry, no knowledge of Lyon’s printing heritage and, more to the point, a complete blank on modern architecture, the docks, the modern industrial areas and the banlieue.

Can you get under the skin of a city as a tourist? Of course not. Can you have a good time? You certainly can. Are we better informed about France’s third city? Well, just a bit. Will we need to go back? I hope so.

Oh yes – and the food. I don’t believe that French cuisine has declined. But I do now believe that British cooking has got a whole lot better.

Only Lyon

Yes, we’re sorry, our first trip abroad for nearly two and a half years and we only managed to get as far as Lyon.

In fact, this modest and self-deprecating blog title is actually Lyon’s badge of choice to head up its tourism offer. Why has Lyon – usually regarded as France’s third city – chosen such an unassuming logo? Of course ‘only’ is an anagram of Lyon. But it still didn’t make much sense to us. Perhaps we are supposed to think ‘only in Lyon will you find …’? On translating it back into French, however, we came up with ‘Uniquement Lyon’. Loses the anagram but we do feel it sells the destination a whole lot better. Stick with what you know? Translations can land you in trouble.

So what did we find in Only Lyon? Here are some of the quirkier bits.

We arrived by train. No not this station ….

…. but a much newer one where the ‘Sortie’ currently discharges you straight into a chaotic building site .

Only Lyon then delivers you into the modern hell of a Westfield shopping centre.

It was a bad start, but things did improve. Lyon’s plane trees, for instance, are magnificent and, in our view, a really distinguishing feature of the city. Perhaps Plane Lyon instead of Only Lyon? But to British eyes, they do look as though they have been high pruned by the giraffes in the city zoo. There is also a very tall graffiti artist - or a very talented giraffe.

Younger plantings and a greater variety of species are beginning to take their place alongside the plane avenues. The city centre is densely built-up, but the rivers Rhône and Saône do provide opportunities to increase urban greening…

… as do the house boats, which line the river banks (below).

Choice of species can be interesting (Lyon is not alone in that of course). Spring is an exciting time in this Lyon suburb and the photograph (right) really doesn’t do justice to the migraine inducing colour combination. Further up the road, there is also an office block which does a thorough job of obscuring the views of the old town, below.

Labelling of larger new specimen trees appears in some places: usually informative (below left and centre) but not exclusively so (below right) and no, it’s not an avacado tree.

Another thing which Lyon does well is provision for two wheelers. Bicycles and electric scooters whizz around the city, often with children on the back (cycles), or in front (on the scooters). When the speed limit for the whole city drops to 30 k/h (around 20 mph) on the 1st April this year, two wheelers will have even more reason to smile. And again, there are some delightful consequences.

But our favourite quirky surprise, by far, is Ememem and ‘flacking’. Thanks to Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ememem) we now know that Ememem are a plural entity, live in Lyon, and go round at dead of night to create mosaics in cracked pavements and facades. ‘Flacking’, apparently derives from ‘flaquer’ (meaning a puddle, presumably linked to the holes in streets which Ememem’s artworks fill). In Lyon, the artist(s) have been dubbed le chirurgien des trottoirs, or the pavement surgeons and ememem refers to the sound of their moped. It’s a great city vibe.

They have also worked in Barcelona, Madrid, Turín, Oslo, Melbourne, Aberdeen and York, so you probably know all about them.

We will return to ‘Only Lyon’ in a future blog but we leave you today with a very Lyonnais poster which made us laugh out loud. Lyon was once a silk town (stand aside Macclesfield and Leek) and is rightly proud of its textile heritage. But it does need some linguistic help.

Collateral Consequences and the Brown Hart Gardens

During our research for the blog on Ukraine, we came across the quirky Brown Hart Gardens in London’s salubrious Mayfair. It’s just opposite the Ukrainian RC Cathedral, in Duke Street. For those of you who were watching television in the 1970’s, this is Duchess of Duke Street territory. For those of you who weren’t, here is a helpful link (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Duchess_of_Duke_Street).

Wowed by the colourful, elevated and peaceful nature of the Gardens, we spent some time exploring and had lunch in the café. The sun was shining and the south facing benches quickly became popular. Others, like us, took photographs of the Cathedral. Unsurprisingly, in this area, it is part of the Grosvenor Estate, but why is it raised up, what is underneath it, why is it a garden and how did it become what it is today? The story of its Victorian beginnings and subsequent development would seem familiar to any design professional working now. Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose.

Duke Street was not always the up market area it is today, despite its proximity to fashionable Grosvenor Square. The story of the Gardens appears to start in the late 19th century and a national outcry over the condition of working-class housing. In the Duke Street area of Mayfair, the Duke of Westminster was working with the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company (IIDC), to upgrade working-class living conditions on the Grosvenor estate.

The IIDC is variously described as a commercial company (www.nationalarchives.gov.uk) and a philanthropic model dwellings company (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Improved_Industrial_Dwellings_Company), which developed high density housing blocks for artisans. Either way, the company needed to turn a profit and at Duke Street seems to have achieved this via a strict code of conduct for tenants, and reduced ground rents from the Duke. References to the building designs being developed by a surveyor rather than architects, raised a wry Terroir smile.

For fascinating and more detailed stuff on finances, planning, urban design and other aspects of social housing provision around Duke Street, we recommend an absorbing article at https://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WMD779_1892_Moore_Buildings_Gilbert_Street_London_UK.

In addition to better housing, the Duke of Westminster also wished to improve the new estate with a coffee tavern, possible to counteract the influence of the numerous public houses in the area, and a spacious community garden to occupy an entire block between Brown Street and Hart Street.

The 1870 Ordnance Survey map (below), illustrates the high density townscape prior to redevelopment. The red ring sourrounds the Brown and Hart Street block. You may be able to pick out the two public houses within this area and a further three within a minute’s walk.

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland' https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

The new garden was designed by Joseph Meston (assistant to Robert Marnock of gardenesque school fame) and was constructed in 1889. It appears on the Ordnance Survey plan of 1895 (below), complete with drinking fountain and urinal. We have yet to locate the position of the coffee tavern; if you know where it was, please let us know. Only one public house appears to remain.

The whole housing development was by built out by 1892; Peabody is now the social housing custodian. The Congregational Chapel to the north east of the new garden (built 1891, designed by Alfred Waterhouse of Natural History Museum and Manchester Town Hall Fame), was sold to the Ukranian Catholic Church in 1967.

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland' https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

The original 1889 garden was clearly at ground level, but survived in that state for little more than a decade, thanks to the Westminster Electricity Supply Corporation. Having worked in the area in the 1890s, the Corporation approached the Grosvenor Estate again to build an electricity substation on the site of the gardens. The proposal involved a large, 7’ high transformer chamber plus housing, with the garden relocated on the roof. Eyebrows were raised, it seems, but complaints had also been growing about the garden, including reference to “disorderly boys”, “verminous women” and “tramps”, and agreement to develop was reached in 1902. “The substation was completed in 1905 to the design of C. Stanley Peach in a Baroque style from Portland stone featuring a pavilion and steps at either end, a balustrade and Diocletian windows along the sides to light the galleries of the engine rooms”. (https://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WMPN21_Duke_Street_Electricity_Sub_station_Brown_Hart_Gardens_London_UK).

Peach specialised in the design of electricity structures, although it seems that the Grosvenor Estate surveyor had quite a lot to do with realising the final configuration of this one. Again, I suspect that we have all seen dramas like that. It is, however, a quite remarkable - and adaptable - structure despite urban clutter disguising some of its grandeur when viewed from the east (below right).

The garden was replaced as promised, with paving and trees in tubs, and was re-opened in 1906. Little seems to be recorded of its 20th century story and it was closed in the 1980s “by the then lessees, the London Electricity Board”, reopening again, briefly, in 2007.

Brown Hart Gardens’ current appearance, described by Grosvenor Estates as “A rejuvenated oasis in the heart of London” is due to – guess what – another regeneration scheme for this part of Mayfair. We are not knocking this; how can an area, last subject to a major refurb in the 1880s, still be fit for use in the 21st century?

The brief, to “rejuvenate a public space over a Grade II listed substation” and “create and manage a beautiful and flexible space to benefit the people who live in, work in, or visit the area” (https://www.bdp.com/en/projects/a-e/brown-hart-gardens/) appears to have been achieved, if one can make that judgement based on a single visit. BDP, a multidisciplinary design consultancy were commissioned to undertake the project and completed the gardens in 2013. Unless there has been another revamp which we don’t know about, it’s wearing well and is beautifully maintained.

Approaching from the Ukrainian end, so to speak, you can be forgiven for thinking that the Gardens are a lofty children’s play area. Climbing through the primary colour tubes to deck level, however, you discover that the space has been designed to appeal to the inner child of all ages - even those who just wish to sit and contemplate.

The piped swirl of colour with its convolvulus flowers looks complicated, but is actually very simple to negotiate or to enter if you want to sit in the middle of it. Once through, the key elements are wooden planting cubes dotted like a board game over the limestone paving, plenty of seats to await your turn to play, a modern café at one end and a discrete but effective water feature which has replaced one of the original stone seats.

Apparently the perimeter planters contain lights and power units and the central planters and seats can be moved around to create different patterns or simply to capture your opponent’s combative rook.

Below: a selection of surprising, attractive and amusing planters.

The overall effect in early spring sunshine is playful, relaxing, surprising, and delightfully isolated from the hurly burly below and beyond. It is a place to sit and read, admire the view, enjoy the plants, talk to neighbours, meet friends, watch the water flow and recharge the batteries (pun intended).

The cafe suits the space pretty well, but that inverted roof angle? Fine when viewed from the gardens but does the side elevation really work with Peach’s

pavillion canopies!?

SUPPORT UKRAINE

“Every day checking on the news with dread in case things are even worse... Feel so helpless.” MT

It is tempting to end the blog at this point, with these simple messages and images. But the issues relating to Ukraine and Russia are complex (what an understatement) and deserve at least a modicum of discussion.

Terroir has no specialist knowledge on the geography, history or politics of Ukraine. We have not even been there, although we have visited Bulgaria, Romania and, briefly, Russia (just Moscow and St Petersburg). So nothing qualifies us to talk with any sort of first-hand experience. A review of even the briefest histories of Ukraine and Russia has left us overwhelmed and confused. So what to do?

We decided to approach friends and family via email or WhatsApp. We asked if the recipient had been to Ukraine and what they felt we should do about current situation, either individually or as a nation. By this means we contacted well over 70 people. Thank you to everyone we pestered and a special thank you to those who responded in time to influence the content of this blog.

The unanimous suggestion for individual action was GIVE MONEY

. The Disasters Emergency Commitee (DEC) link is below but there are plenty of other options.

Image right: poster on door of Ukranian RC Cathedral, Duke Street, London

Other suggestions, in order of popularity, were:

More sanctions: there were many references to gas and oil but some went further - “By this [sanctions] I mean severing aLL trade with Russia (and not just the bits that suit us) … . Of course this would raise prices and probably shortages here but that's a price worth paying I think” TT. “My biggest worry is that the issue will fade into the background not to mention the people who will not make a sacrifice of their own to help the people of Ukraine (Higher prices for food, fuel, etc).” MK

Refugees: speed up/simplify visa applications system for refugees (“It would be nice if our government could stop being such bastards over visas“ PT), take in more refugees and help and support the refugees who get to the UK. “I think that, as a country, we would like to think that we will give a warm welcome to refugees but the actuality throughout history has not been at all the same“ DG. “We could have a family here. Plenty of room but they need their own country.” PM

Action against Russian money in UK: “deployment of the wealth of oligarchs supporting Putin to benefit the people of Ukraine” RW

Send supplies: send weapons; send items which Ukrainians actually need; sending money is more efficient.

NATO: don’t get NATO involved; get NATO involved in humanitarian work

No fly zone: impose and enforce.

Communication: strengthen diplomatic links; communicate with Russia via channels the people would trust. Works both ways though: “[Russian friend produced an article by] a famous journalist [John Pilger] which basically said everything that was happening could be laid at the feet of the West. I’m sure there is some truth in what he says but whatever the evils and decadence and weakness and mistakes of the West, there is surely only one person responsible for what is happening and that is Putin.” SC

Prayer: keep Ukraine in our thoughts/prayers

Safe Corridors: “probably wishful thinking, but create or improve safe corridors which lead to the places where Ukrainians wish to go” HN

British Government: all comments critical and mostly unprintable

Putin: again, largely unprintable but – “Putin is a man obsessed surrounded by brutal people who are keeping him there in their own self interest.” PM; “abolish toxic masculinity” RW.

There are other views though: “I cannot help but feel sorry for the people of Russia whose country will carry the guilt for Putin’s actions.” DG. “The Russians we know in the UK are as shocked as we are.” LD

Talking to others with a knowledge of Russian history, Terroir has begun to realise that the world cannot afford to ignore Russia’s feelings of insecurity, an emotion which often underpins antisocial actions. Terroir put this to a friend who has visited both Ukraine and Russia on numerous occasions, and we are deeply indebted to his response, excerpts of which we reproduce below:

“I'm trying to keep in touch with my Russian friends - those I have heard of I am sure are horrified about what is going on, although they are expressing it somewhat obliquely - partly I suspect because it’s very dangerous to say outright that the war is wrong, and partly because that's what Russians do anyway! But my friends are intellectuals and western looking, mostly in St Petersburg, the " window on the west", [and] have visited US, UK and other European countries - if they were English they would read the Guardian. Much harder to tell what the poorly educated Russian in the heartland thinks, who only get their information from Russia's answer to the Daily Mail and Fox News.

I think the importance of Russian insecurity, even paranoia, is not understood or discussed enough in the West. Anyone over 40 who grew up in Russia, grew up being told that the West were nasty imperialists out to do down the USSR. This was the world Putin was brought up in - he was in the KGB … . Russia went from being the top dog in an empire covering a third of the world to a single country with a collapsed economy. I remember when in the 1990's we were celebrating Russian Independence Day my friend Yuri, then in his 60's said ‘Independent from whom?’, even though he had been a dissident because of his interest in psychoanalysis and as he put it to me once " had been treated as a non-person"

In the 1990's and 2000's The West reached out to the Baltic states and Eastern European countries, but much less so to Russia - why did we not invite them to join NATO in 1995? Someone said that Russia now must feel as people in the UK would have felt in the late 20th century if Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands had all joined the Warsaw pact.

Going further back Russia has nearly always been governed by autocrats who combined incompetence with malevolence - Putin is in the tradition of most of the 19th and early 20th century Tsars, Lenin and Stalin.

Although most of the Ukrainians I met were proudly Ukrainian … the way the Government has flipped between Russia leaning and West leaning in the last 30 years suggests that there are probably divisions within the population - and we know there are many in Crimea and the East who want to be Russian.

None of this excuses Putin but it might help to understand what is going on.” https://sites.google.com/site/peterdtoon/

Help Ukraine to a good future.

Please donate to https://donation.dec.org.uk/ukraine-humanitarian-appeal

© Y Fontanel

Tinners

Four of us were gathered together this week (celebrating St David’s Day), and one of us asked what Cornwall meant to each of us.

Here are the responses:

Tintagel Castle, The Eden Project and St Mawes

China clay moonscapes and clotted cream

Cliffs and wild coasts, holiday homes and Posy Simmonds cartoons

Arsenic

Arsenic: how very perceptive.

As our collective list shows, Cornwall is good on memorable and iconic landscapes. Go to the home page of the Cornwall Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and you will see a moody and romantic image of a tin mine engine house and stack, perched on the edge of a rugged coastal cliffs (https://www.cornwall-aonb.gov.uk/). These structures are symbolic of ‘an extended period of industrial expansion and prolific innovation’ (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1215/) which contributed enormously, not only to the landscape of Cornwall, but also to the industrial revolution, the British economy, to mining around the world and, of course, climate change.

The long term impact of mining and industrialisation on the planet was probably impossible to imagine during the heady years of technological development, sizeable profit margins and world-wide influence. But there were other issues, however, which could and should have been recognised at the time. Arsenic was just one of these.

Let’s go back to the beginning. Mining has a very long history in Cornwall, probably starting in the Bronze Age. Medieval mining of tin was so significant in the south west that separate Stannary Courts and Parliaments were set up in Devon and Cornwall in the early 14th century. The UNESCO world heritage site ‘Cornish and West Devon Mining Landscape’ (granted in 2006) focuses on the period from 1700 to 1914, and specifically mentions the significance of the ‘remains of mines, engines houses, smallholdings, ports, harbours, canals, railways, tramroads, and industries allied to mining, along with new towns and villages’. Of such fragments are romantic landscapes created.

Terroir’s induction into Cornish Tin Mining was provided by the Geevor Tin Mine (https://geevor.com/), on the north Cornish coast, near the villages of Pendeen and Boscaswell. It is part of the St Just Mining Area and the site is now run by Pendeen Community Heritage. Ironically, Geevor is a ‘modern’ mine established around 1906 and expanded significantly after World War I. The mine closed in 1990 and the pumps, which drained the mine, were switched off in 1991. Despite its modernity by UNESCO standards, the mine describes itself as the ‘Key Centre within the Cornish Mining World Heritage Site’. But, of course, if there were plenty of earlier mines remaining, with which to interpret Cornwall’s mining history, there might be no need for a World Heritage Site.

It took us two mornings to get our heads around the vocabulary of developers, stopers and samplers; of cross cuts, lodes, drives, pillars and box holes; of wagons, locomotives, rocker shovels, skips and, of course the grizzly. We learnt to interpret the photographs of young men, stripped to the waste, undertaking gruelling, skilled, manual labour in hot, deep, cramped, under-sea, mining levels. We began to understand the efficiencies brought by Trevithick’s steam technology (in, for instance, economics of production, and in underground safety through water pumping, ventilation and personnel transport) and the increased impact of steam-driven mining on Cornwall and around the world. We got a handle on the complexities of processing the ore to a marketable product which could be sold on to manufacturers. And we began to understand the cost in human life in winning, processing and supporting the entire industry.

Below:

Upper and middle row - a historical range of mining technology

Lower row - views of the Geevor Mine processing area

Below left: a model of the 20th century shaft and winding gear as it once was, and will be again. Below right: the winding gear currently under repair.

Despite this growing understanding of mining issues, the landscape around Geevor Mine seemed surprisingly innocent.

But, as a guide explained to us, the expanses of waste gravels and green fields below us would once have been occupied by extraction paraphenalia and a shanty town housing miners and all the ancillary workers who serviced the pre 20th century mines – candle makers, charcoal-burners, carpenters, smiths, smelters, carters, chandlers, shop keepers, ale-house keepers, and so on. Even in the 20th century (below right), it would have been a busy area.

The stonehenge style kit on the left, by the way, is the remains of the stamps, the steam-powered ore crushers which would have thudded relentlessy, 24 hours a day.

All the rest is gone now, leaving just these romantic ruins…

But how wonderful to be working in an industry which leaves no massive scars, no starkly white China clay pyramids, no coal heaps, no shale bings, no slag heaps. All the ‘arisings’ from tin mining can be sold on as aggregate for construction, can they not? Well, maybe only after technological developments made it worth reprocessing the waste rock heaps for the tin they still contained, while chucking the unsaleable rubbish into the sea.

And we are not just talking tin here. Tin and iron come up as an oxide, accompanied by sulphide minerals such as copper, zinc, lead, bismuth, antimony and, yes, the mineral beloved of murder mysteries, arsenic.

Arsenic became a saleable bi-product of tin mining and, in the 19th century, was processed by burning in a calciner which trapped the arsenic as soot. Children were often employed to scrape it out of the chamber and chimney. Our guide explained that despite wearing an early forerunner of PPE, most of these children never lived beyond their teens. Miners’ life expectancy was also short – perhaps into their twenties and thirties. It seems likely that, in these polluted and impoverished living conditions, a woman’s life expectancy was also limited. As so often, our romantic landscapes are built on the problems of the past.

And you still want to know what a grizzly is? It’s a set of parallel steel bars used to sieve out the large chunks of ore. Gravity sent the small stuff through the bars into the skip loading boxes below. The grizzly man had to break up the larger stuff with a hammer.

Lighthouse Lizard

Cornwall is famous for its stories but, as with all good tales, they change with the passing of time. Even the Cornish Wreckers are now being subjected to rehabilitation, as Terroir discovered on a visit to the Lizard Lighthouse.

There’s a lot going on at the Lizard Peninsula. Three main landowners (National Trust, Cornwall Wildlife Trust, Natural England) and an absence of fences, enhance the feeling of a windblown wilderness. It’s host to a large, if somewhat fragmented National Nature Reserve, forms an important part of the equally fragmented Cornwall Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and is fringed with crashing seas, rocks, cliffs and, for those with a head for heights, the South West Coast Path. Lizard Point is also the southern-most tip of Britain and home to our southern-most lighthouse - and self-catering holiday let.

Our visit to the lighthouse was made the more dramatic by being sandwiched between storms Eunice and Franklin. You would think that there would be nothing much to blow over but even Trinity House does overgrown suburban windbreaks.

The first Lizard lighthouse was completed in 1619 (https://www.trinityhouse.co.uk/lighthouses-and-lightvessels/lizard-lighthouse), over a decade before warning braziers were constructed on the South Foreland in Kent, overlooking the Goodwin Sands (https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/south-foreland-lighthouse/features/the-history-of-the-lighthouse-) and many years before the first Eddystone light was operative in 1699 (https://www.britannica.com/topic/Eddystone-Lighthouse-Eddystone-Rocks-English-Channel).

This early lighthouse was built by one John Killigrew who, despite opposition from local villagers (who foresaw a steep decline in income from shipwrecks), was granted a patent to construct a warning of hazardous waters, provided that the light was extinguished at the approach of ‘the enemy’. It was described as being, ‘a great benefit to mariners’, but as the ship owners refused to contribute to its upkeep, the bankrupt Killigrew was forced to demolish his philanthropic venture some 20 years later.

Peter Stanier’s ‘Cornwall’s Industrial Heritage’ notes that it was a “private lighthouse … opposed by Trinity House and local wreckers.” Trinity House says, “Many stories are told of the activities of wreckers around our coasts, most of which are grossly exaggerated, but small communities occasionally and sometimes officially benefited from the spoils of shipwrecks, and petitions for lighthouses were, in certain cases, rejected on the strength of local opinion; this was particularly true in the South West of England”. How tactful (Terroir’s highlighting). On this subject, we can also recommend a ‘Stories in Stone’ video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BdKHi4JYrag.

Whatever the reason, subsequent lighthouse applications failed until, in 1748, Trinity House supported local landowner Thomas Fonnereau, in a successful lighthouse bid. The building (in operation by 1752) consisted of two towers with a cottage between them, which had a window facing each tower. Coal fires were lit on the towers, and required bellows-blowers to keep the fires burning brightly; if the fires dimmed, an overseer in the cottage would encourage their endeavours with a blast from a cow horn.

Trinity House took over responsibility for the lights in 1771, and, in 1811, replaced the coal fires with oil lights. Three additional cottages were also constructed in 1845. But the biggest change occurred with the construction of an engine room, in 1874, using “caloric engines and dynamos” to power the light and a new fog horn. Even more staff were required so more cottages followed. In 1903, a high powered rotating carbon arc light was installed on the east tower, thus eliminating the need for any light on the west tower. The arc light was replaced with an electric filament lamp in 1936. LEDs will follow soon. Automation arrived in 1998, and the resident lighthouse keepers worked their final shift.

The engine room is now a Heritage Centre, thanks to the Heritage Lottery Fund. Exhibits range from, unsurprisingly, engineering and lamps (see below), to communications, living and working conditions and a soft play area for trial constructions of your own lighthouse tower.

The tour of the lighthouse is a must, led by Hamish the cat (no longer the kitten as noted in his job description) and assisted by a guide who one suspects is descended from those who “officially benefited from the spoils of shipwrecks”, certainly knew the light house keepers, and came suitably attired in hat, coat and bright red Wellington boots. She entertained and informed an assorted rabble of adults, children and adolescent cat, with delightful and diverting composure.

Right: Puss-in-carrier and Wonder-Women-Guide-in-Boots

The lighting system currently consists of the most magnificent four panel rotating optic which was installed in 1903. These magnificent panels, framed in Cornish granite, and, according to Wonder-Woman-Guide, resting in a tank of mercury, rotate continuously. To non-physicists like Terroir, the optics seem to represent some of the best and simplest of art nouveau, but presumably this is merely an illusion based on association with the date they were installed. We were also captivated by our guide’s allusion to the history which these lenses would have illuminated, including the passage of the Titanic on her way to meet her iceberg fate.

Such was the intensity of the light, that the rotating beam provided night long illumination, upsetting both the local ecology and the local inhabitants. As a result, a blackout was provided for the lantern room window closest to the village.

The change to electric filament lamps also allows for a simple back-up, should the ‘duty’ lamp fail before it is due to be changed. If you peer closely at the image (right) you may be able to detect a vertical lamp (the ‘duty’ lamp, in Terroir parlance) and the horizontal back up lamp.

Since automation, the back up lamp can be raised into position remotely, by the Trinity House depot in Harwich. A further back up is also available for the ultimate unexpected event. A couple of other items, no longer required but still in situ, are illustrated below.

And why does the optic rotate continuously? We have heard at least two convincing explanations: due to the structure of the lenses, a static optic, bathed in sunlight, could cause a pretty nasty fire. In addition, an optic system which has been in operation continuously since 1903, just might fail to start again.

Southern-most tip of Britain. Southern-most light house. But what about those holiday cottages? The southern-most crown is claimed by the nearby, converted Lloyds’ signal station, built in 1872 to provide communications between passing shipping and Lloyds of London (white building, just visible, right). But six of the Lighthouse cottages are also holiday lets, available via the National Trust. Terroir feels that the ‘most southerly status’ is probably theirs.

Memorial Landscapes

Early in 2014, the then Prime Minister, David Cameron, set up a Holocaust Commission, to “ensure that the memory and the lessons of the Holocaust are never forgotten and that the legacy of survivors lives on for generation after generation“. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/398645/Holocaust_Commission_Report_Britains_promise_to_remember.pdf

The brief was threefold: to create a striking and prominent new national memorial, to collect and record the testimony of the diminishing numbers of holocaust survivors, and to create a world class learning centre to enable others to understand and learn from that legacy.

Led by Mick (Sir Michael) Davis, the Commission’s report was published in 2015 and suggested three potential locations for a memorial and learning centre. These were The Imperial War Museum London, Potters Field (a site between Tower Bridge and the former London City Hall) and a site on Millbank, close to Tate Britain. The blue touch paper had been lit. The debate on where and what the new national memorial should be, has been raging ever since.

In 2016, and seemingly out of nowhere, Victoria Tower Gardens, immediately to the south of the Houses of Parliament, was put forward as a possible Holocaust Memorial site.

After an international design competition, the commission was awarded, unanimously, to a team led by Adjaye Associates and Ron Arad Architects. This was in September 2017.

The design - a massive line up of 23 bronze fins - was heavily criticised for, amongst other things, its size, its dominance over its setting and also because it looked remarkably similar to the design Adjaye Associates had submitted for Canada's National Holocaust Monument (it didn’t win).

Above - visualisation of Adjaye Associates’s design in situ at Victoria Tower Gardens

The idea of placing the monument in Victoria Tower Gardens (a mere 2.5 ha of well used public park) created a veritable storm of comment and criticism from all quarters.

As you can imagine, the planning process was a nightmare. A planning application was submitted at the end of 2018, followed by revisions in 2019. The application was subsequently ‘called in’ for a public inquiry, immediately before Westminster City Council’s planning meeting - where the application was unanimously refused. The public inquiry was held (remotely) in 2020 and, following the Inspector’s recommendation, planning permission was finally granted by Communities Secretary Robert Jenrick MP, in July 2021. By the September, The London Gardens Trust had launched a challenge on the basis that decision-makers failed to properly consider the impacts of the development (https://londongardenstrust.org/campaigns/victoria-tower-gardens/). The resulting Judicial Review will take place next week on the 22nd and 23rd of February.

Let’s take a look at the Gardens. Victoria Tower Gardens are designated Grade II on the Historic England Register of Parks and Gardens (https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1000845?section=official-listing). After construction of the Houses of Parliament, the site of the park was ‘occupied by wharves, a cement works, an oil factory, and flour mills’. Terroir can imagine that this was felt to be an inappropriate neighbour to Barry and Pugin’s Parliamentary construction and, by 1879, money had been found to lay out a public park.

Both images reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland' https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

Let’s take a walk. At around 2.5 ha (6 acres) it is extraordinary what elements are contained within it, and what socially valuable functions it provides.

From a distance, and dwarfed by Parliament’s Victoria Tower, it appears to be small, flat and grassy. Perhaps the ideal space for a physically large memorial of international and historic significance.

But approaching over Lambeth Bridge towards the south end of the park, its true values begin to unfold.

First up is the playground, in use even on a chilly, February, term time weekday morning. From the play equipment (see right hand images below) this is, obviously, Horseferry Playground!

Beyond the slide and half submerged horses, the Gardens open out onto a wide, grassy space, framed by statuesque plane trees and book-ended by stunning vistas of Parliament. Surely the perfect spot for a memorial? The size of the proposed memorial structure is such that this ‘space’ and the views to it, from it and within it, would be dominated by the giant bronze fins. Terroir suggests that the Victoria Tower Gardens would become the Holocaust Memorial Apron, no longer a park in its own right, and cut off from the symbol of democracy which gave birth to the park. In other words, a piece of green heritage would be destoyed to create an, albeit very significant, memorial. Which should take priority? Well, the Holocaust Memorial doesn’t have to go here. Victoria Tower Gardens, by definition, does.

The first three images (above) reveal the Victoria Tower and Houses of Parliament in all their glory. Already the view has been compromised by the low level Education Centre, with its station platform outline - alien to the pattern and shapes of the architecture behind it and only slightly mitigated by its green roof. The fourth view (right) look south towards the Buxton Memorial and the apex of the triangular park. All views would be obliterated or radically changed if the Holocaust Memorial was built here.

But, I hear you cry, it’s just a small area of lawn, with hardly anyone using it. Remember this a February morning. Think about spring lunchtimes; sunny after school time; sun bathing weekends; evening promenades; a space for tourists, workers, local inhabitants, politicians, school children, teenagers, the retired, dog walkers, strollers. It’s not just the London Gardens Trust which is opposing this proposal. Take a look at the Save Victoria Tower Gardens Park website (https://www.savevictoriatowergardens.co.uk/), or the Thorney Island Society (https://thethorneyislandsociety.org.uk/ttis/). This is a much loved and well used park. Sufficient size for its current community? A tranquil space? Think what it would be like with the addition of the significant number of visitors likely to be attracted to a Holocaust Memorial of the proposed scale and significance.

The adjacent Thames (above) adds much to the Gardens. The waterscape becomes an intrinsic part of the park itself - including the views outward to London landmarks - but also makes the open space feel larger and the Embankment, with its mature plane trees, provides a seductive promenade and sitting area.

The park planting, although not ‘in your face’ spectacular, no doubt provides all round seasonal delight. A glimpse of February’s charms (below) was very welcome.

But wait a minute - isn’t this a Memorial Park already? Indeed it is. There are three memorials located here and all touch on human rights and democracy.

The Buxton Memorial Fountain (left) commemorates the emancipation of slaves and the contribution of some key anti-slavery campaigners. Designed by Samuel Sanders Teulon, it was first installed on the edge of Parliament Square in 1865, removed in 1949 and finally reinstated in Victoria Tower Gardens in 1957. The base is granite and limestone, and the mosaic decoration and enamelled roof are, in Terroir’s view, particularly attractive.

The Burghers of Calais (right), a cast of Rodin’s powerful 1889 sculpture, despicts the six leading citizens of Calais who agreed, in 1347, to surrender the keys of the town, and their own lives, to Edward III in return for an end to King Edward’s 11 month siege, and sparing the lives of the rest of the town’s people.

The story goes that the Burghers’ lives were also spared by the intervention of Edward’s Queen, Philippa of Hainault. The original scupture is in Calais, of course, but this is one of four subsequent castings, which was bought by the National Art Collection Fund in 1911. Rodin is said to have visited London to advise on where it should be placed (https://www.royalparks.org.uk/parks/victoria-tower-gardens/things-to-see-and-do/burghers-of-calais).

Tucked in a corner, under the shadow of British democracy, stands the memorial to Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel. Surprisingly - perhaps suspiciously - modest, it is, nethertheless, a place to pause, to consider the treatment of the suffragettes, and to honour their achievements.

There are two possible ways forward in this Memorial siting dilemma. One is to move the Memorial site elsewhere, and a prime location would seem to be the Imperial War Museum London. The other is to significantly reduce the above ground impact of the Memorial and continue at the same site. This will not solve all the problems, nor will it satisfy many protestors, but Hal Moggridge, who gave evidence at the public inquiry, regarding the potential harm of the proposal, has drawn up an alternative scheme to demonstrate that a lighter touch is possible. The scheme is illustrated below.

Both images © H Moggridge

Having more than one alternative to a disputed proposal can often inspire greater confidence when searching, or fighting, for a better option.

Downing or Drowning?

As political open spaces go, the garden behind 10 Downing Street must currently one of the most infamous. Access is extremely limited, of course, but the number of images on the internet does make a digital visit remarkably easy.

Gardens are powerful allegories and have always played a role in politics and the search for influence and control. What does this one in London SW1A tell us?

Originally, the garden had power stamped all over it. But prior to becoming the haunt of our political leaders, Sir Anthony Seldon’s history of Downing Street suggests a more modest inauguration. (https://www.gov.uk/government/history/10-downing-street). Apparently the Romans created their Londinium settlement on Thorney Island, a marshy piece of land in an area now called Westminster. No one made much of a go of the new community and Seldon suggests it was ‘prone to plague and its inhabitants were very poor’.

But lo, a series of kings arrived (Canute, Edward the Confessor and William I), and a great abbey was built. Government and the Church had arrived, and this section of Thames-side was now ‘on the map’.

Seldon also reports that the first building known to be on the Downing Street site was the medieval Axe Brewery. What glorious irony.

Then Henry VIII got involved and, via various political manoeuvrings, created the spectacular Whitehall Palace immediately adjacent to what is now Downing Street. Of course Henry needed a place to hunt and the area which later became St James’ Park, was laid out and enclosed.

From Van der Wyngarde’s View of London, 16th Century, British Library

Remnant walls have been discovered embedded in the dining room of No 10 and in the garden. (https://londongardenstrust.org/conservation/inventory/site-record/?ID=WST027a). With this shift of royal influence to Whitehall, domestic residences were soon being constructed around the Park and the Palace, for those wishing to live close to the power source.

In 1682, one George Downing obtained the lease and engaged Christopher Wren to build a cul-de-sac of terrace houses. Seldon comments, ‘It is unfortunate that he [Downing] was such an unpleasant man. Able as a diplomat and a government administrator, he was miserly and at times brutal.’ Seldon continues, ‘In order to maximise profit, the houses were cheaply built, with poor foundations for the boggy ground. Instead of neat brick façades, they had mortar lines drawn on to give the appearance of evenly spaced bricks. In the 20th Century, Prime Minister Winston Churchill wrote that Number 10 was: “Shaky and lightly built by the profiteering contractor whose name they bear”’. You just couldn’t make it up.

And here comes the exciting bit. Thanks to the London Gardens Trust, we can report a first mention of a Downing Street garden: ‘a piece of garden ground scituate in his Majestys park of St. James's, & belonging & adjoining to the house now inhabited by the Right Honourable the Chancellour of his Majestys Exchequer’. https://londongardenstrust.org/inventory/picture.php?id=WST027a&type=sitepics&no=1 Even more exciting, there is a picture, painted by one George Lambert at around the time of Walpole’s residency.

© Museum of London

As you can see, the image depicts the formal, rectilinear, controlled expanse of a fashionable, early 18th century garden. Two be-wigged gentlemen stand amongst straight lines – railings, paths, steps, lawns, trees – all backed by a substantial brick wall which clearly separates politics from St James’s Park. The only light relief as a classical looking statue, set into the wall, and a small black dog. This is a garden in corsets; the rolling English Landscape tradition has yet to happen and 20th century domestic gardens are not even a twinkle in anybody’s eye.

From then on, the houses on Downing Street were constantly remodelled, joined together, improved and extended, a process which continues today.

George II tried to give the house to First Lord of the Treasury Sir Robert Walpole. Sir Robert turned him down but suggested it become an official residency and actually moved in, in 1735.

Extract from ‘A New Pocket Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster 1797’ British Library

But what about the gardens? Looking at the Google image below, there have been radical changes. The Downing Street grounds have been cut off from St James’s Park and have, to some extent, embraced informality. The whole area behind house numbers 9 - 12 Downing Street has been combined into a single unit of about a quarter of a hectare. Earl Mountbatten has his own space, overlooking the Park.

Google Imagery © 2022

The ‘front garden’ is visible – just - to all and sundry, and goes for the formal, short grass, bedding plants and hanging baskets combination. Perfect for that sweeping shot from television cameras. No chance of Terroir getting in to get some more attractive shots.

This back garden is no longer a statement of power and influence in its own right but a utility which has been forced to cater for a multitude of functions. These functions include the garden as play area for young families (Blairs, Browns, Camerons, Johnsons), as a place to grow vegetables (Michelle Obama’s influence on Sarah Brown), a setting for important visitors (including the Barak Obama/Cameron barbeque for military personnel), as stage for state visits and formal events, asan occasional venue for London Square Open Gardens Weekend, as a resource for the increasing numbers who work there and, now, as a Covid facility for fresh air, meetings, explanations, apologies, thanks and other forms of showing appreciation to the in-house team.

As a result, it is appears that the garden has a bit of everything except a cohesive design. From recent internet images, we have spotted a mix of small trees, large shrubs, whole shrubberies, herbaceous planting, perennial planting, bedding plants, hedges, bulbs in beds, bulbs in grass, raised beds, urns, yards of Wisteria, mounds of roses, lots of close mown lawns, assorted path surfaces and two ghastly municipal style lighting bollards. Oh and a huge terrace for, err, sitting out on.

It also appears that the garden sports some massive plane trees but this is actually a ‘borrowed landscape’ and these classic Londoners lean in and peer down from outside the garden walls.

View from Horse Guards Road of the ‘borrowed plane trees’ and the back of 12 Downing Street Google Imagery © 2022

It’s all maintained by the Royal Parks. Do look at this YouTube video (https://youtu.be/RMwL3GYtqjo) to get a real taste of what it takes to keep the space immaculate for any ocasion, with or without warning.

What does this horticultural jumble tell us? I would suggest:

A lack of respect for open spaces; you can take a virtual tour of the inside of 10 Downing Street (https://artsandculture.google.com/u/0/story/twXxuEIPr4FZJA) but not of the garden.

A failure to demonstrate good design.

An own goal for lack of sustainable management and biodiversity.

A lost opportunity for British horticulture.

A return to a good old fashioned head gardener.

Are we too harsh?

Perce-Neige

Snowdrops: the first flowering bulb of spring. What’s not to like?

When the Head Gardener of Gatton Park in Surrey takes you on a tour of the garden’s snowdrops, in advance of their first ‘open day’ of the year, snowdrops deliver at their delicate best. Set in a Capability Brown landscape perched on the North Downs, and accompanied by stunning views and the scents of Daphne and Sarcocca (Sweet Box), it’s a pretty sensual experience.

But is this delicate, early spring flower (the snowdrop, not the Sarcocca which is anything but delicate), able to overcome the clichés and past associations which follow it around?

Snowdrops in poetry are definitely seen as symbols of hope, purity and solace. I do have problems with the Romantic poets, however. Try Wordsworth (1770 to 1850):

From To a Snowdrop

“Chaste Snowdrop, venturous harbinger of Spring,

And pensive monitor of fleeting years!”

This ‘chaste’ thing is quite something for a flower which, in a stiff breeze, is quite happy to flaunt its frilly underskirts. What is the first thing we do when up close and personal with a snowdrop? Turn a flower upside down to admire the delicate floral layers within.

Tennyson (1809 -1892) was also a fan of the snowdrop purity angle. Think of this famous two liner from

The Snowdrop

“Many, many welcomes,

February fair-maid!”

or this extract from

The Progress of Spring

“Wavers on her thin stem the snowdrop cold

That trembles not to kisses of the bee”

No way was Tennyson going to identify the snowdrop with a knight in shining armour or a king’s courtesan.

Christina Rossetti (1830-1894) (technically brilliant, but in my view very capable of schmaltzy platitudes) actually fares better:

Another Spring (first verse)

“If I might see another Spring

I’d not plant summer flowers and wait:

I’d have my crocuses at once,

My leafless pink mezereons,

My chill-veined snowdrops, choicer yet

My white or azure violet,

Leaf-nested primrose; anything

To blow at once, not late.”

Or

The First Spring Day (again Verse 1)

“I wonder if the sap is stirring yet,

If wintry birds are dreaming of a mate,

If frozen snowdrops feel as yet the sun

And crocus fires are kindling one by one”

At Gatton Park it’s the fiery aconites which this year out-compete the crocuses, and we’ve already commented on the sweet smelling Daphnes even if they are D. bholua rather D. mezerium/mezereons.

The Hellebores (below left and centre) and a witch hazel (below right) also contribute to the spring show.

Despite the best efforts of the Romantics, or possibly because of them, the Victorian snowdrop began to develop a darker personality. Some suggest that, as snowdrops became popular to plant in graveyards, the flowers became associated with bad luck and a harbinger of death rather than spring. (https://escapetobritain.com/snowdrop-history-galanthus-nivalis/)

The 20th century snowdrop, however, seems to have survived this bad press and became a very popular addition to gardens and parks as well as poetry. Enthusiastic amateur and professional horticulturalists have developed many new varieties with subtle differences in the size of flower and the pattern of green markings on and within the blooms. Gatton Park features Galanthus elwesii and G. ‘Flore Pleno’ as well as G nivalis.

Perhaps it is not surprising, therefore, that 20th century Snowdrop imagery seems to be much more robust, and references to purity have tended to shift to more sombre themes.

East Coker, No. 2 of T S Eliot’s Four Quartets (surely tautology - how likely is it that there would be three or five quartets?) is, inevitably, rather disturbing but, in my view, very exciting and, in this extract, very pithy about hollyhocks:

“What is the late November doing

With the disturbance of the spring

And creatures of the summer heat,

And snowdrops writhing under feet

And hollyhocks that aim too high”

(Please don’t tread on the flowers).

My favourite Snowdrop discovery, however, is Louise Gluck’s Snowdrops - perfect for a 21st century in pandemic.

“Do you know what I was, how I lived? You know

what despair is; then

winter should have meaning for you.

I did not expect to survive,

earth suppressing me.

I didn't expect

to waken again, to feel

in damp earth my body

able to respond again, remembering

after so long how to open again

in the cold light

of earliest spring”

Many gardens open to the public in February to display their collections. Terroir will be going back to Gatton Park on Sunday 6th February. This is not a woodland garden display, but rather a spread of snowdrops naturalising through the Edwardian flower and shrub beds, under massive veteran trees, or spilling down grassy slopes. The ’drops trim the Brown landscape with green and white lace, showing that once more, snowdrops are able to remember,

“how to open again in the cold light of earliest spring“.

See you there.

Heaven and Hell